12,000 year-old rock art proves humans thrived in Arabia’s deserts earlier than believed

Archaeologists uncover life-sized rock art and tools in Arabia, showing humans thrived in the desert after the Ice Age.

Archaeologists in northern Arabia discovered monumental rock art and tools that reveal how early people adapted to desert life after the Ice Age. (CREDIT: Nature Communications)

The arid deserts of north Arabian Arabia do not seem to be the kind of climate early humans would have loved, but new finds are rewriting that hypothesis. Archaeologists have found life-size camel, ibex, gazelle, and horse engravings that have been carved high onto desert cliffsides, and tools, beads, and indications of temporary camps.

Collectively, these discoveries point to the fact that individuals not only lived through here during the final Ice Age and the warmer Holocene era, but they also left behind a work of art that remains towering above the sand all those years later.

Overturning Traditional Ideas

Researchers assumed for decades the heart of Arabia was empty during the coldest phase of the Last Glacial Maximum, roughly 25,000 to 10,000 years ago. Vast ice sheets locked up water elsewhere in the globe, turning most of Arabia into a hyper-arid wasteland, too hostile to harbor any permanent human settlement. Human beings were assumed to have avoided the region until the more hospitable wet conditions arrived with the Holocene.

That vision has since changed. Archaeological digs at three locales—Jebel Arnaan, Jebel Mleiha, and Jebel Misma—reveal that occasional bodies of water began to appear as early as 17,000 years ago. Never lush lakes, these shallow depressions trapped just sufficient amounts of water to serve as lifelines. The data reveals that people settled in much earlier than had been assumed, depositing not only stone tools and campfires but also monumental works of art.

The secret is in ancient lake bed sediments known as playas. Drilling trenches at Jebel Misma revealed alternating deposits of wind-blown sand and clays, proof that water deposited here in brief, more humid intervals. Luminescence dating revealed that these shallow lakes began to exist between 17,000 and 13,000 years ago—thousands of years earlier than the whole humid phase of the Holocene.

These temporary pools weren't permanent oases. They weren't linked to any remains of dense vegetation or to deep earth. Instead, they were temporary, forming after rainfalls and evaporating again. Nevertheless, even these temporary spates of water would have proved adequate for migrating societies to use as stepping stones across the desert.

Giants on the Cliffs

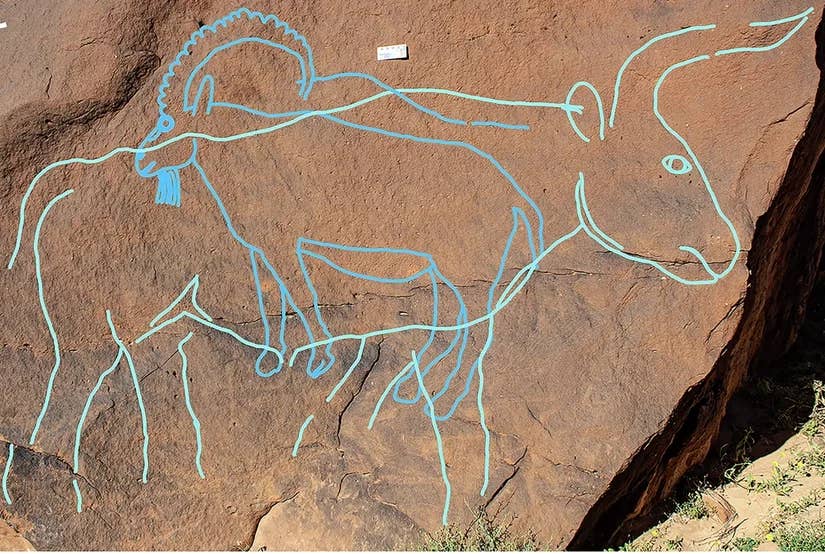

Near the playas, 62 rock art panels containing 176 engravings, 130 of them life-size, were documented by archaeologists. The size is imposing: camels that stand three meters tall, ibex sculpted with arched horns, horses and gazelles chiseled in realistic detail. Panels were set in dizzying heights. In one place, the engravers climbed narrow ledges to strike 23 life-size camels and equids on two cliff faces, each 23 meters wide. The amount of work suggests these were no random doodles but meaningful expressions of culture.

"These massive carvings are not mere rock art – they probably were statements of presence, access, and identity," said Dr. Maria Guagnin of the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, the study's director. Dr. Ceri Shipton of University College London said, "The rock art marks water sources and lines of movement, possibly marking territorial claims and memory between generations."

Unlike other ancient engravings buried in rock fissures, these Arabian carvings were meant to be viewed. Some are almost 40 meters above the desert floor, their visibility a testament to their symbolic gravity.

Clues Beneath the Art

Beneath the engravings, archaeologists uncovered stone tools, hearths, beads, pigments, and ceramics, even remnants of animal bones. In Jebel Arnaan's one of the trenches, a tool that could have been used for engraving was buried in layers dating from about 12,000 years ago. Hearths were radiocarbon dated and confirmed people were present at the site about 12,800 to 11,400 years ago, during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period also found in the Levant.

The toolkits are a tale of cultural connection. El Khiam and Helwan points—stone arrowheads first made in the Levant—scrapers, drills, and blades were found by scientists. Beads made out of imported sea-shells from over 300 kilometers away suggest trade or long-distance travel. Pigments like green mineral powders suggest symbolic or ceremonial activities. All these finds link Arabia's desert people to wider cultural networks far into the distance beyond the sands.

Adaptation and Symbolism

Camels figure prominently among the carvings, making up nearly three-quarters of all the figures. Their large size, well-defined shape, and placement in prominent positions suggest they had distinctive symbolic importance. A few of the camels were carved with bulging necks, which may have symbolized males in rut while mating. If so, the carvings may reflect seasonality based on rainfall.

Other animals—ibex, gazelles, equids, and even one aurochs—appear, taking in the diverse fauna that formerly traveled through the desert. With passing time, the style of the engravings evolved. Earlier figures were more realistic, followed by ones that were more stylized, sometimes overwriting past occurrences. This layering not only reflects artistic development but also the manner in which these locations continued to hold meaning over generations.

Dr. Faisal Al-Jibreen of the Saudi Heritage Commission said, "This unique way of symbolic expression is part of a certain cultural heritage adapted to residing in a challenging, desert environment."

Filling the Gaps in Arabia's Story

The results complete a major gap in the archaeological record of Arabia. There had not been any human occupation from the Last Glacial Maximum through to the start of the Holocene previously, and so these findings show that human groups adapted to seasonal resources much sooner than was previously believed, and that they left behind evidence of cultural traditions that crossed deserts and mountains.

"Interdisciplinary approach to this project has already begun to fill a basic gap in northern Arabia's archaeological record between the LGM and the Holocene," said Michael Petraglia, leader of the Green Arabia Project. "It provides insight into the adaptability and ingenuity of early desert dwellers."

The study involved researchers from the Saudi Ministry of Culture, Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, University College London, Griffith University, and others.

Practical Impacts of the Study

These results give us more than a glimpse into the past. They show how people adapted to climate stress, which is extremely relevant today. By understanding how the earliest societies managed in fluctuating and volatile conditions, modern researchers are better able to value the roots of human resilience.

The engravings also elicit cultural expression and communication, highlighting the significance that art can have as both remembrance and survival technique.

For Saudi Arabia, the research adds depth to cultural heritage, offering potential for preservation, learning, and tourism that will enable humans to experience rich human history.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Related Stories

- Historic 2,600-year-old Turkish artifact finally decoded: 'The Mother' goddess revealed

- Step inside 280 ancient Etruscan tombs without ever leaving home

- After thousands of years, researchers think they’ve finally found Noah’s Ark

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.