A glass bead and a green laser helps scientists observe lightning form in real time

Scientists trap a tiny glass sphere with lasers and watch it charge, revealing new clues about lightning and the hidden physics inside glass.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

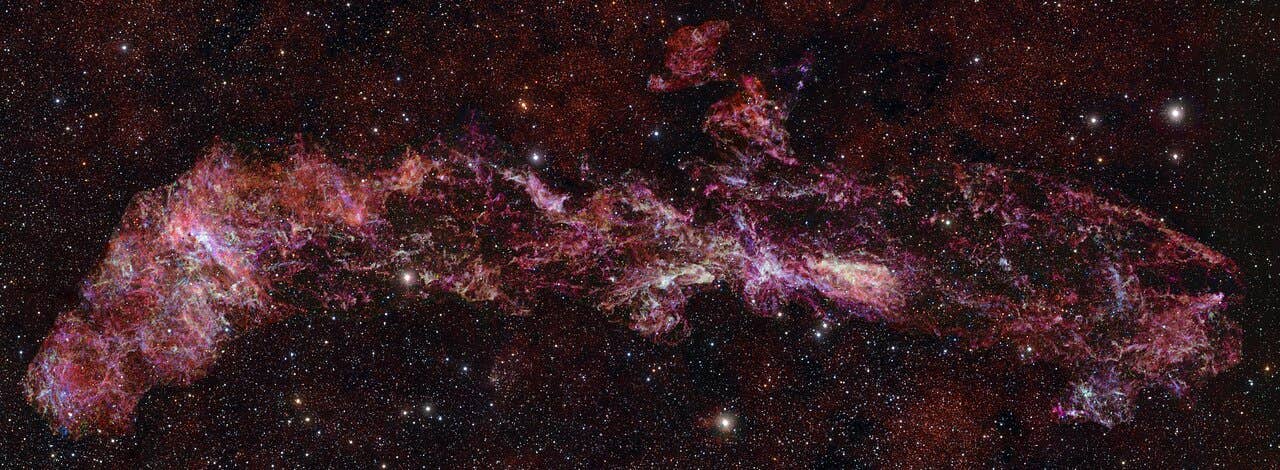

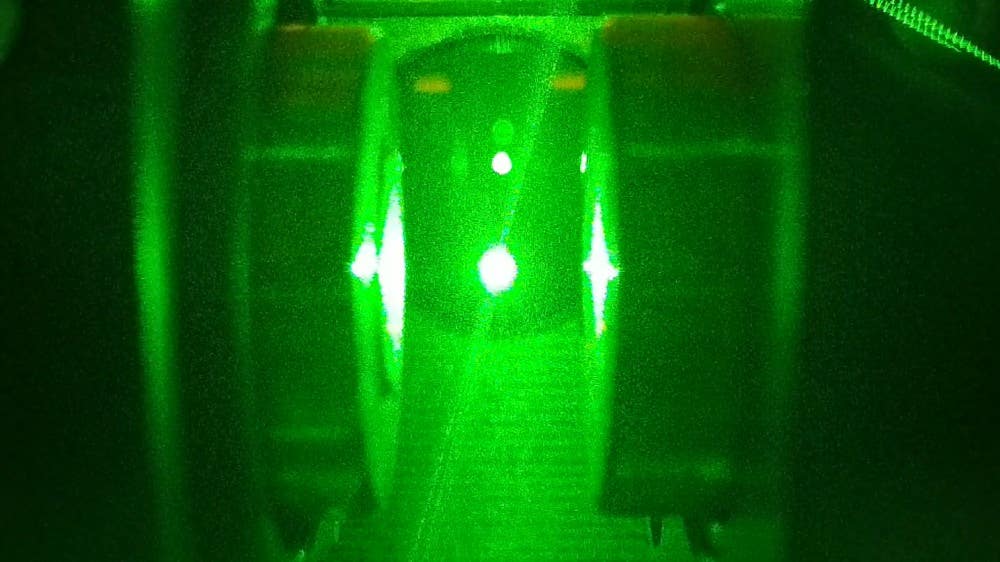

Optical Trap. Catching a micron-sized particle is challenging. To get the job done, two laser beams come in handy. Acting like tweezers, they can trap, secure, and charge a solitary particle. (CREDIT: Andrea Stöllner/ISTA)

A single green laser, a glass bead smaller than a bacterium and a lab in Austria are helping you see lightning in a new way.

Scientists have found a way to watch an object build electric charge in real time, one electron at a time. They did it by catching a tiny silica particle in midair with light and letting a powerful laser do the rest. The work revisits the spirit of the famous oil drop test from a century ago, but with tools that can track the smallest changes imaginable.

At the Institute of Science and Technology Austria, two laser beams intersect inside a metal chamber and form a trap. When a speck of high purity silica drifts through the crossing light, it freezes in place. From there, the researchers apply an electric field and measure how the particle moves. If it carries charge, it wiggles. If it does not, it stays quiet.

“We can now precisely observe the evolution of one aerosol particle as it charges up from neutral to highly charged and adjust the laser power to control the rate,” said Andrea Stöllner, a PhD student at the institute.

Her team includes former postdoc Isaac Lenton and Assistant Professor Scott Waitukaitis. Together they built a system sensitive enough to detect a single electron. Their study appears in Physical Review Letters.

The Moment the Charge Begins

The setup does more than hold a particle still. It also reveals that the very light used to trap it causes the charging.

During tests, Stöllner watched as the bead slowly gained a positive charge while exposed to strong green light. The growth was steady at first. Then it slowed. It never quite stopped. Instead, it crept upward for hours.

The team discovered that the effect followed a two photon process. Two particles of light strike the silica at once. That energy kicks one electron free. Each escape leaves behind one unit of positive charge.

“The first time I caught a particle, I was over the moon,” Stöllner said. “Scott Waitukaitis and my colleagues rushed into the lab and took a short glimpse at the captured aerosol particle. It lasted exactly three minutes, then the particle was gone. Now we can hold it in that position for weeks.”

Before each run, the group resets the charge with soft X rays. The rays make the air briefly conductive, so any extra charge leaks away. Then the laser switches on and the climb starts again.

The growth follows a neat rule. Double the light and the early charging rate rises fourfold. That square pattern is the hallmark of a two photon event.

The Hidden World Inside Glass

Two green photons do not pack enough punch to knock an electron from solid glass under normal conditions. So where do the electrons come from?

The answer lies in defects. Silica is not perfect inside. It has tiny flaws and disorder that create extra energy levels, like hidden steps inside an energy ladder. Some of those steps sit close enough to the surface that two photons can push an electron out.

To test the idea, the researchers compared their laser results with a separate technique called photoelectron yield spectroscopy. In that method, ultraviolet light shines on powdered silica and the escaping electrons are counted. The pattern showed an exponential rise in available states inside the material.

When the team laid their laser data over the spectroscopy curve, the shapes matched. The charging method even reached down to lower energy levels than the older test. That result points to a rich, unseen landscape of electronic states inside the glass.

Not every detail is settled. Another model suggests heat may help some electrons escape after absorbing light. But one result does not fit that picture. The implied temperature would be far above the room’s 23 degrees Celsius, even though silica barely warms under green light. Future tests with added heat or ultraviolet beams should settle the question.

Why a Speck of Dust Matters

This is not just a physics trick. It may help solve one of nature’s loudest puzzles.

Clouds are filled with ice crystals and airborne particles known as aerosols. When they bump into each other, they swap electric charge. Over time, storms become electric engines. But the first spark of lightning remains hard to pin down.

One theory points to ice itself. Another points to high energy particles from space. In either case, the electric fields measured inside clouds often seem too weak to trigger a bolt.

“Our new setup allows us to explore the ice crystal theory by closely examining a particle’s charging dynamics over time,” Stöllner said.

Her model particles are smaller than real ice crystals, but they behave in striking ways. As charge builds, it occasionally breaks free in tiny bursts. Picture countless minuscule flashes inside a cloud. Could they join forces and grow into a lightning strike?

Stöllner smiles at the idea. “Our model ice crystals are showing discharges and maybe there’s more to that. Imagine if they eventually create super tiny lightning sparks, that would be so cool.”

Beyond storms, the method could reshape how researchers study air pollution, cloud formation and even disease spread. Aerosols carry viruses and chemicals. Their charge affects how they move and where they land.

The same technique may also give engineers a new way to probe materials. By charging a particle nearly to the point where air itself breaks down, scientists create a steep electrical barrier. That barrier acts as a measuring stick for electronic states. It is a lab inside a bead of glass.

What started as a trapped speck now opens a door to understanding electricity in places you cannot touch, from the heart of a cloud to the flaws inside glass.

Practical Implications of the Research

This work could improve storm prediction by refining models of how lightning starts inside clouds. It may also lead to better air quality science, since charged particles behave differently in the atmosphere.

In materials research, the method offers a new way to map hidden electronic defects, helping engineers design stronger glass and better optical devices.

The ability to control charge at the single electron level may one day benefit sensor design, microelectronics and studies of airborne health risks.

Research findings are available online in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Related Stories

- Gamma-rays trigger lightning and alter atmospheric chemistry

- Microlightning in water droplets may have ignited life on Earth

- Say what? Scientists are trying to catch a lightning bolt with a giant laser

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.