A massive new project maps dark matter using 100 million galaxies

A new study using old telescope images reveals where dark matter hides, reshaping how scientists see the structure and future of the universe.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

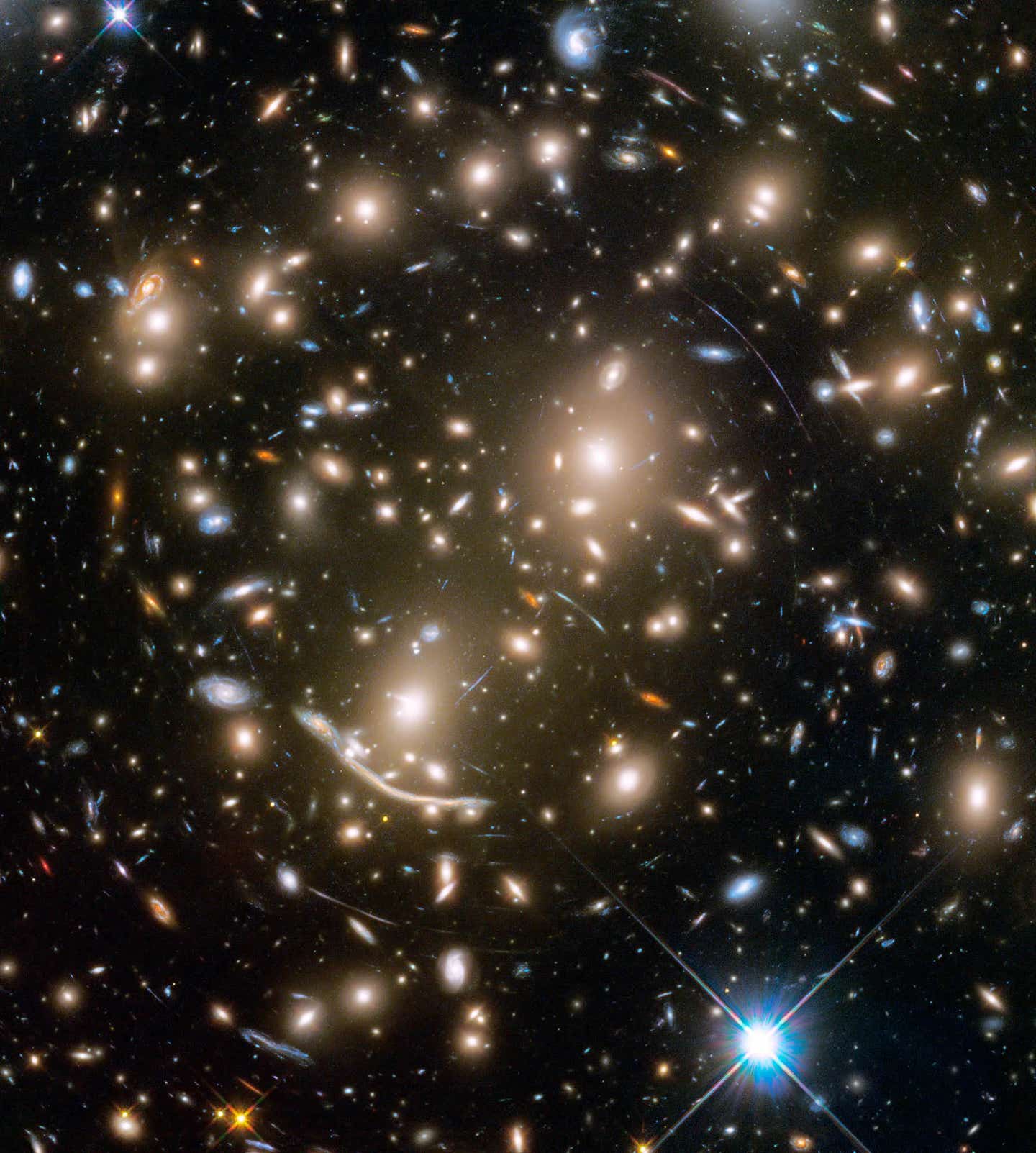

A massive new project maps dark matter using 100 million galaxies, turning old telescope data into a clearer picture of the universe. (CREDIT: NASA, ESA, and J. Lotz and the HFF Team (STScI))

Most of the universe cannot be seen with any telescope, and that is not because scientists lack powerful tools. It is because the cosmos is ruled by substances that give off no light at all. Dark matter and dark energy make up about 95 percent of everything that exists, shaping galaxies, stretching space, and guiding cosmic history. Now, a massive new study gives you one of the clearest views yet of how that invisible universe is arranged.

Astronomers have released one of the largest gravitational lensing catalogs ever created. The project, called DECADE, measured the shapes of more than 100 million distant galaxies to map how matter is spread across space. The work used a special camera in Chile to uncover where even unseen matter is hiding.

Gravitational lensing from faraway galaxies

Gravitational lensing happens when light from faraway galaxies bends as it travels through space. Large clumps of matter, including material that cannot be seen, warp that light almost like glass bends a beam. In most cases, the change is tiny. A galaxy may appear slightly stretched or tilted. On its own, that means little. Across millions of galaxies, it reveals how the universe is built.

This technique gives you a direct way to trace dark matter. It shows how matter gathers into strands and clumps that form a vast, unseen web. That web determines where galaxies grow and how they move.

For decades, scientists studied only a few million galaxies at a time. Newer projects pushed that into the tens of millions. DECADE goes even further, reaching beyond efforts that came before. It does not rely on a new telescope or fresh images alone. Instead, it took another path.

A Treasure Found in Old Light

The data came from the Dark Energy Camera, known as DECam. It sits on a four meter telescope in Chile and has been watching the sky for more than ten years. From 2013 to 2019, it powered the Dark Energy Survey, a famous project that mapped much of the southern sky. But when that survey ended, something surprising became clear.

The camera had gathered far more information than anyone had used.

Thousands of images taken for other reasons had never been examined for gravitational lensing. Some were meant to study small galaxies. Others focused on stars or distant clusters. All of them captured light that could also be used to trace dark matter.

Recovering left-over data

Scientists decided to recover that “leftover” data. The DECADE team gathered public observations taken before December 2022 and processed them as if they were part of a single super survey. That collection covered more than 21,000 square degrees of the sky.

Not all of it could be used. Dust, bright stars, and crowded regions can confuse measurements. The team narrowed their focus to a high quality area in the northern sky, covering about 5,400 square degrees. Then they ran the images through the same careful processing system used by the Dark Energy Survey.

In the end, computers found around 470 million objects. Many were stars or too faint to study. Others were blended into their neighbors. After several rounds of checks, just over 107 million galaxies remained.

That number alone tells a story. It makes DECADE one of the largest lensing projects ever attempted.

Measuring Cosmic Stretch

Measuring a galaxy’s shape is harder than it sounds. Telescopes blur images. Earth’s atmosphere adds noise. A galaxy might look stretched simply because of the camera, not because of the universe.

To solve this, the team used a clever method called Metacalibration. For each galaxy, the computer created four subtle imitations of the image, each one warped just slightly. By measuring how the shape changed, the software learned how sensitive that galaxy was to distortion.

This allowed scientists to tease out which stretching came from gravity and which came from the instrument. Galaxies that were clearer and less noisy were given more weight. Fuzzier ones counted less.

After all corrections, the data reached a density of about five galaxies per square arcminute. That puts it on par with other major surveys and strong enough to test the basic ideas of how the universe evolves.

Hunting for Errors Before They Hunt You

Because lensing signals are so faint, mistakes can easily sneak in. Light from a star spreads across the camera in a known pattern, called the point spread function. If that pattern is not modeled perfectly, it can fake a cosmic signal.

The DECADE team tested this in dozens of ways. They checked whether bright stars appeared too wide and looked for any link between measurement errors and sky conditions like seeing or haze. They searched for strange patterns that gravity should not create.

Again and again, the tests came back clean.

Then came another step. Scientists built fake universes inside computers. They inserted pretend galaxies with known distortions into pretend images and ran them through the same software. By comparing what went in with what came out, they measured any remaining bias.

The correction needed was small, a few percent, and well understood.

The universe after the Big Bang

“Our measurements show no conflict with what we see in the early universe,” said Chihway Chang, an associate professor at the University of Chicago and leader of the project. Cosmic background radiation reveals what the universe looked like soon after the Big Bang. Some past surveys hinted that the nearby universe might tell a different story. DECADE does not see that split.

“This is a well tested model that keeps holding up,” Chang said.

The lead analyst, Dhayaa Anbajagane, explained why this matters. “Weak lensing is best at measuring how clumpy matter is,” he said. “That tells us how galaxies and clusters formed over time.”

When the DECADE results were compared with earlier data from the Dark Energy Survey, the picture became even sharper. Together, the projects now include 270 million galaxies across about one third of the entire sky.

Alex Drlica-Wagner, who led the observing campaign, said the outcome was not guaranteed. “We did not know if recycled data could really work for precision science,” he said. “Now we know it can.”

A New Way Forward

DECADE also sends a message to future missions. You may not need perfect images for every study. Valuable science can come from reusing what already exists.

That lesson matters as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory prepares to scan the sky in coming years. If more images can be trusted, more science will follow.

The DECADE catalog is already being used to hunt dwarf galaxies and map hidden matter in new ways. Researchers from the University of Chicago, Fermilab, Argonne, and many other institutions worked side by side to make this happen.

“We were all in the same hallway,” Chang said. “It changed how we worked and what we thought was possible.”

With more data from the southern sky still coming, this invisible map of the universe will only grow sharper.

For now, what DECADE offers is simple and profound. Even without seeing it, you can now trace the skeleton of the cosmos with greater clarity than ever before.

Practical Implications of the Research

By refining how dark matter and dark energy behave, this research helps sharpen the basic model of the universe. That model affects everything from how galaxies form to how the universe will end.

Better maps of hidden matter also improve galaxy distance tools, which can aid future space missions.

The project proves that reused data can drive major discoveries, saving time and cost for new research. It also strengthens confidence in current cosmology, offering a clearer foundation for future studies of gravity, space, and time.

Research findings are available online in The Open Journal of Astrophysics.

Related Stories

- After nearly a century of looking, researchers may have finally detected dark matter

- New quantum sensors aim to detect hidden forces behind dark matter

- Dark matter and dark energy may not exist, new research finds

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.