A new type of microscope lets scientists observe life unfolding inside cells

Tokyo team builds a label free microscope that sees tiny and large structures in living cells at once, across 14 times wider range.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

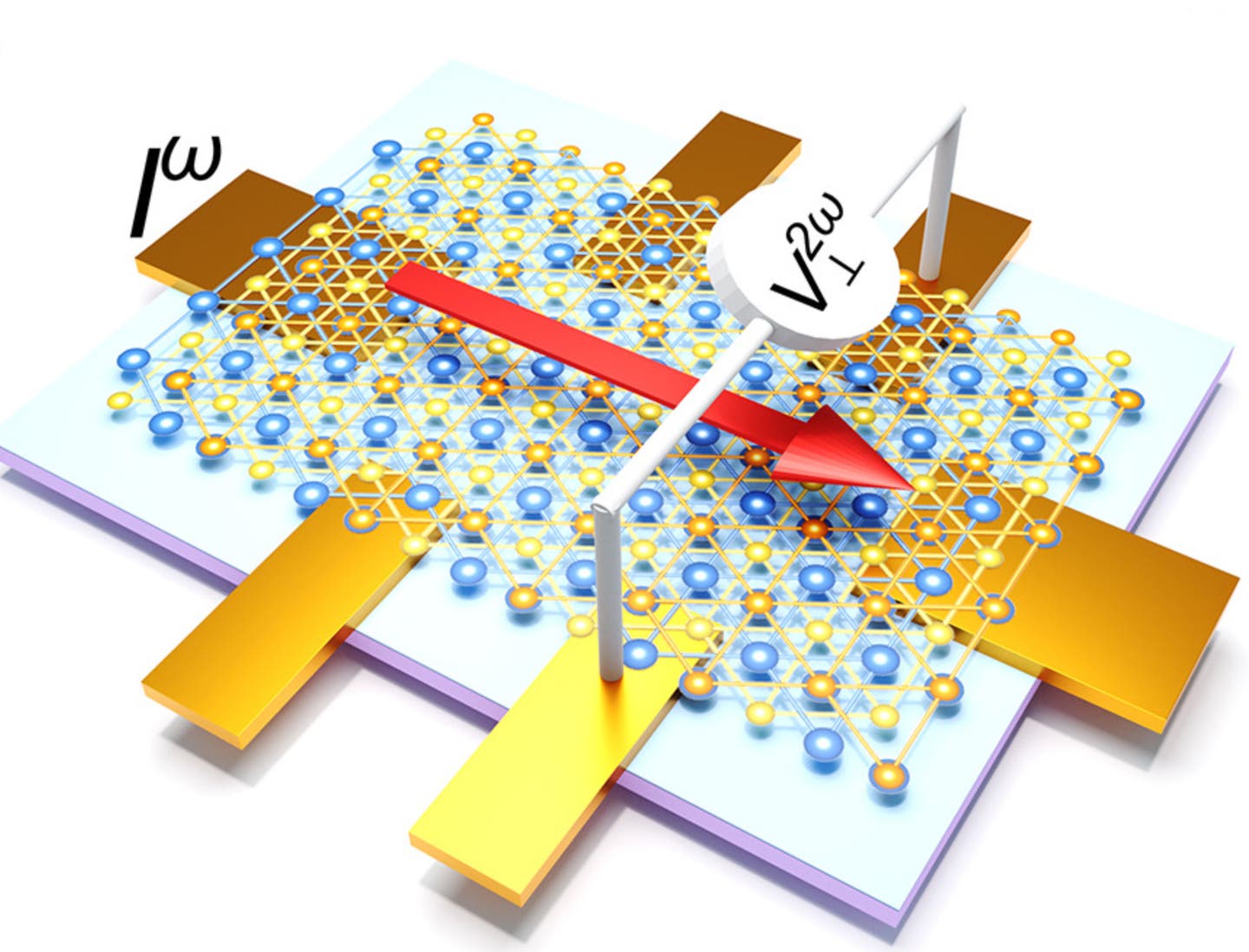

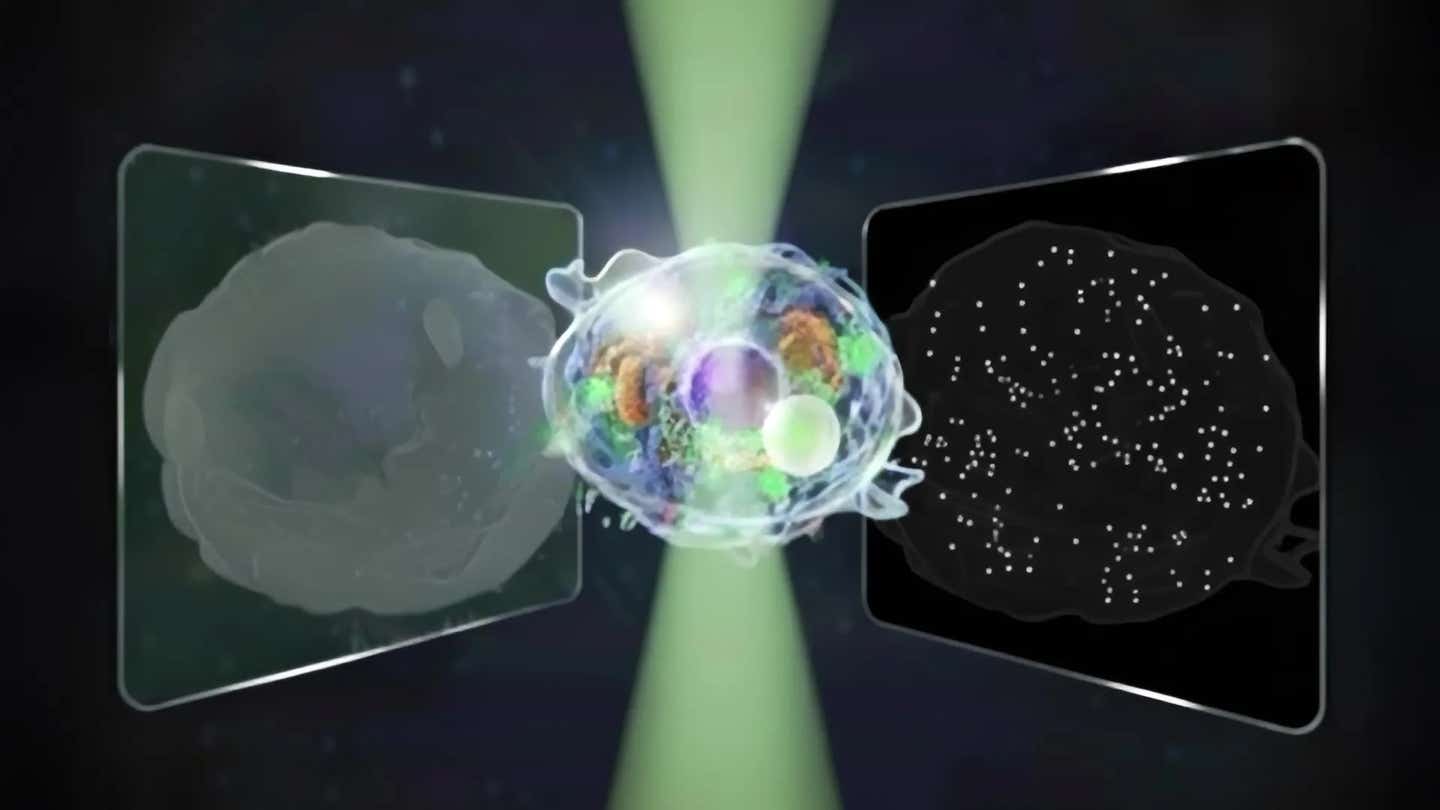

Conceptual illustration of the bidirectional quantitative scattering microscope, which detects both forward and backward scattered light from cells. (CREDIT: The University of Tokyo)

A new kind of microscope is giving scientists a way to watch life inside cells with a clarity that feels almost unfair. Instead of choosing between seeing big structures or tiny particles, researchers can now track both at once, in living cells, without dyes or labels that might stress them. For anyone who cares about how drugs work, how cells die or how viruses move, that is a big deal.

Why Old Microscopes Forced a Tough Choice

Modern biology has leaned on two powerful, but limited, label free tools. Quantitative phase microscopy, or QPM, looks at light that passes through a cell. It excels at showing you whole cells and larger inner parts, down to a bit over 100 nanometers. You can see outlines, organelles and broad shape changes, but smaller structures fade into the background.

Interferometric scattering microscopy, called iSCAT, works very differently. It watches light that scatters backward from tiny objects, small enough to include single proteins. With iSCAT you can track a single nanoparticle as it zips through a cell. The tradeoff is harsh though. You lose the wider context and cannot easily see how that particle moves through the full architecture of the cell.

So until now, if you wanted to study life inside a cell, you had to pick. You either focused on the big picture or zoomed in so far that you lost it.

A Two Way Path For Light

At the University of Tokyo, researchers Kohki Horie, Keiichiro Toda, Takuma Nakamura and Takuro Ideguchi asked a simple question. What if you capture both directions of scattered light at the same time? Their answer is a new instrument that records forward scattered and back scattered light in a single image, then cleanly separates the two signals.

The system extends the usable intensity range by a factor of fourteen compared with a standard quantitative phase microscope. That wider range lets the same camera pick up faint signals from nanoscale particles and strong signals from larger structures without one swamping the other.

The heart of the technique is careful optical design and smart computation. The team encodes information from forward and backward traveling light onto one sensor, then uses a reconstruction method to tease them apart while keeping noise very low. “Our biggest challenge,” Toda explains, “was cleanly separating two kinds of signals from a single image while keeping noise low and avoiding mixing between them.”

Because the method is label free, it does not require fluorescent tags or stains. That means cells are not forced to take up foreign chemicals, and you can watch them over long periods with less worry about damage.

Watching Cells As They Approach Death

"To prove that the microscope really worked across sizes and time scales, our group chose a dramatic test case. We pointed the system at living cells as those cells moved toward death, and recorded one image after another, Toda explained to The Brighter Side of News.

"On the microscale, our team followed the motion and shape of inner structures. We could see how large components shifted, how boundaries changed and how the inner landscape of the cell slowly broke down. At the same time, we tracked tiny particles at the nanoscale. Those small specks jittered and drifted, and their behavior changed as the cell’s condition worsened," he continued.

By comparing forward and back scattered light from each particle, the team could estimate both size and refractive index. Refractive index tells you how strongly a particle bends light, which hints at its makeup. In simple terms, the microscope does not just show that a particle exists; it also says something about what kind of particle it might be.

“I would like to understand dynamic processes inside living cells using non invasive methods,” Horie says. This new setup brings that goal much closer.

From Cells to Viruses and Beyond

The current system can pick up very small features, but the researchers are already thinking smaller. Toda says they hope to study exosomes and viruses next, and to measure their size and refractive index in different samples. These objects are key messengers in the body and important players in disease, yet they are hard to watch in their natural state.

The team also plans to probe how cells move along the path toward death in more controlled ways. By changing conditions, then checking their results with other techniques, they want to uncover the sequence of events that leads a healthy cell to shut down.

Because the method is gentle and label free, it fits well with long term monitoring. In the future, you could picture it running quietly while cells grow, divide, respond to drugs or endure stress, catching both subtle shifts and sudden failures.

Practical Implications of the Research

This new microscope could become a powerful tool for drug development. If you can watch how both large structures and tiny particles inside a cell respond to a new compound, you gain a deeper sense of how that compound really works. That can help you spot side effects earlier and refine treatments before they reach patients.

In the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, the method may support better testing and quality control. Long term, label free observation lets companies check how cell based products behave over time, without having to alter those cells with dyes. That could improve the safety and consistency of therapies such as cell based drugs or engineered tissues.

For basic science, the wider intensity range and dual view of scattered light open a new window on cellular life. Processes like viral infection, immune responses, fat storage or programmed cell death involve both big structural changes and tiny players. Seeing them together, in real time, will help researchers build more complete models of how cells stay healthy or fail.

If the technique extends to exosomes and viruses as planned, it could also aid early disease detection and monitoring. Those particles carry signals about what is happening deep inside the body. A tool that measures their size and optical properties in a routine way might one day feed into diagnostic tests.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Related Stories

- Scientists use light-controlled nanorobots to quickly grow bone cells

- Researchers discover the cellular cause of Parkinson’s disease

- Breakthrough antibody delivery system targets hidden cancer cells

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.