A really weird asteroid has just gotten a little weirder

Asteroid 3200 Phaethon has long been known to exhibit comet-like behavior, as it forms a tail and brightens when it comes near the Sun.

[Apr. 26, 2023: JD Shavit, The Brighter Side of News]

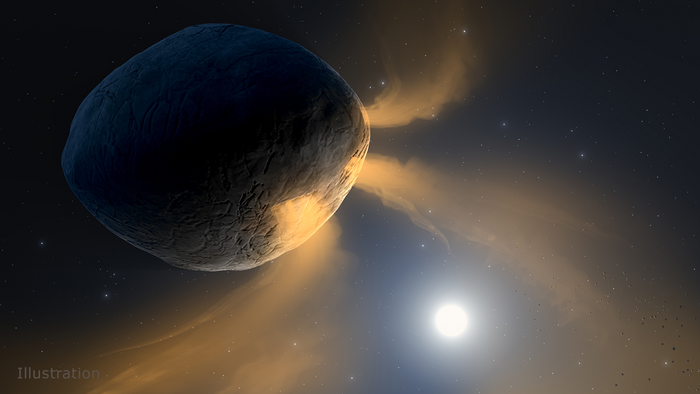

This illustration depicts asteroid Phaethon being heated by the Sun. The asteroid’s surface gets so hot that sodium inside Phaethon’s rock likely vaporizes and vents into space, causing it to brighten like a comet and form a tail. (CREDIT: NASA/JPL-Caltech/IPAC)

Asteroid 3200 Phaethon has long been known to exhibit comet-like behavior, as it forms a tail and brightens when it comes near the Sun. However, a recent study conducted by Qicheng Zhang, a PhD student at the California Institute of Technology, and his colleagues reveals that Phaethon’s tail is not made of dust as previously thought, but is instead composed of sodium gas.

The study used two NASA solar observatories and found that Phaethon’s tail only appears bright in the filter that detects sodium and not in the filter that detects dust. This discovery overturns 14 years of thinking about Phaethon and suggests that asteroids like Phaethon, rather than icy comets, may be responsible for some meteor showers.

Comets are typically composed of ice and rock, and as they approach the Sun, their ice is vaporized, leaving a trail along their orbits, which is why they form tails. On the other hand, asteroids are mostly rocky and do not form tails as they approach the Sun. P

Phaethon was initially discovered by astronomers in 1983, and its orbit matched that of the Geminid meteor shower. Since then, it has been regarded as the source of the meteor shower, even though it is an asteroid and not a comet.

Related Stories

NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) first spotted a short tail extending from Phaethon in 2009 when the asteroid was closest to the Sun. STEREO observed the tail again in 2012 and 2016, suggesting that dust was escaping from the asteroid's surface when heated by the Sun.

However, in 2018, observations from NASA’s Parker Solar Probe showed that the trail of debris left by Phaethon contained far more material than it could have shed during its close approaches to the Sun. This led Zhang’s team to wonder whether something else was behind Phaethon’s comet-like behavior.

Zhang’s team looked for Phaethon's tail during its latest perihelion in 2022 using the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), which has color filters that can detect sodium and dust. They also searched archival images from STEREO and SOHO and found the tail in 18 of Phaethon’s close solar approaches between 1997 and 2022.

This two-hour sequence of images from the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) shows Phaethon (circled) moving relative to background stars. (CREDIT: ESA/NASA/USNRL/Karl Battams)

SOHO’s observations showed that Phaethon's tail appeared bright in the filter that detects sodium but did not appear in the filter that detects dust. The tail's shape and the way it brightened as Phaethon passed the Sun matched exactly what scientists would expect if it were made of sodium but not if it were made of dust. This evidence indicates that Phaethon's tail is made of sodium, not dust.

Karl Battams of the Naval Research Laboratory, a member of Zhang’s team, said that they have a “really cool result that kind of upends 14 years of thinking about a well-scrutinized object” and that they have also done this using data from two heliophysics spacecraft, SOHO and STEREO, that were not intended to study phenomena like this.

Now that they have identified Phaethon’s tail as being made of sodium, the team is left with a crucial question: If Phaethon does not shed much dust, how does it supply the material for the Geminid meteor shower we see each December?

The Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO) on the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) imaged asteroid Phaethon through different filters as the asteroid passed near the Sun. (CREDIT: ESA/NASA/Qicheng Zhang)

The team believes that a disruptive event occurred a few thousand years ago, causing a piece of the asteroid to break apart under the stresses of Phaethon's rotation and ejecting the estimated billion tons of material that make up the Geminid debris stream. However, what that event was remains a mystery.

The Geminid meteor shower is one of the most reliable annual meteor showers, visible from both hemispheres of the Earth. Every December, the shower produces dozens of bright shooting stars per hour, making it a favorite for stargazers and amateur astronomers. The shower's source, asteroid 3200 Phaethon, has long been a subject of interest and study for scientists.

The recent discovery that Phaethon's tail is made of sodium gas, rather than dust, has added a new layer of mystery to this enigmatic asteroid. If Phaethon doesn't shed much dust, how does it supply the material for the Geminid meteor shower? What caused the asteroid to eject the billion tons of material estimated to make up the Geminid debris stream?

These questions have puzzled scientists for decades, but a new mission from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) could hold the key to unlocking the secrets of Phaethon and the Geminid meteor shower. The mission, called DESTINY+ (short for Demonstration and Experiment of Space Technology for Interplanetary voyage Phaethon fLyby and dUst Science), is scheduled to launch in 2024 and arrive at Phaethon in 2026.

DESTINY+ will be the first spacecraft to visit Phaethon and study its surface and environment up close. The mission will carry a suite of scientific instruments, including cameras, spectrometers, and dust collectors, to gather data about Phaethon's composition, structure, and history. The spacecraft will also attempt to capture and analyze samples of Phaethon's dust, which could reveal clues about the asteroid's origin and evolution.

"DESTINY+ will revolutionize our understanding of Phaethon and the Geminid meteor shower," said Masaki Fujimoto, the DESTINY+ project scientist at JAXA. "We hope to answer some of the fundamental questions about this mysterious asteroid and its role in producing one of the most spectacular meteor showers in the sky."

One of the key goals of the mission is to determine the source of the Geminid debris stream. Scientists have proposed several theories over the years, ranging from Phaethon's fragmentation due to its fast rotation to its collision with another asteroid or comet. However, none of these theories can fully explain the amount and distribution of material in the Geminid stream.

"We know that Phaethon is the source of the Geminid meteor shower, but we don't know how it produces so much material," said Zhang, the lead author of the recent study on Phaethon's tail. "The DESTINY+ mission will provide us with the first direct measurements of Phaethon's surface and dust, which will help us understand how this asteroid works."

In addition to studying Phaethon, DESTINY+ will also test new technologies for interplanetary travel and exploration. The spacecraft will use a solar sail to travel to Phaethon, a technology that harnesses the pressure of sunlight to propel the spacecraft through space. The mission will also demonstrate a new type of miniaturized spectrometer, which could be used for future missions to study the atmospheres and surfaces of other planets and moons.

"We are excited to pioneer new technologies and techniques for exploring the solar system," said Fujimoto. "DESTINY+ will be a landmark mission that pushes the boundaries of what we can achieve in space exploration."

For more science stories check out our New Discoveries section at The Brighter Side of News.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.