After nearly a century of looking, researchers may have finally detected dark matter

A strange halo around the Milky Way may be dark matter glowing for the first time, after 15 years of NASA satellite data.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

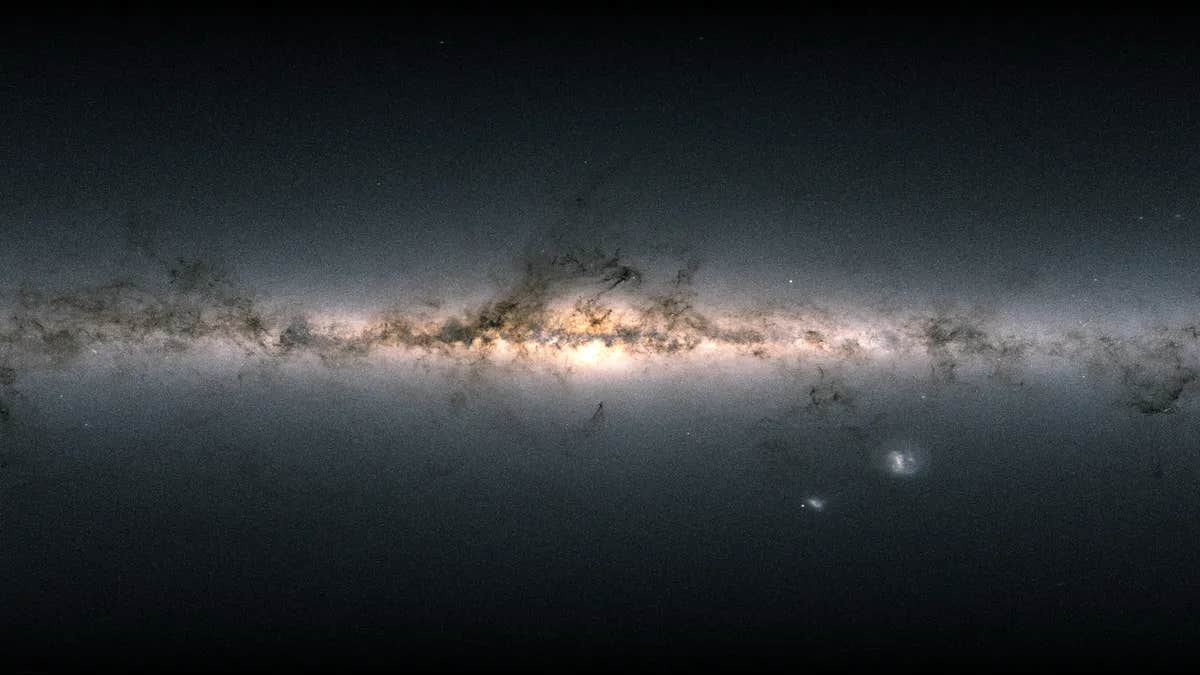

A faint glow around the Milky Way may be the strongest hint yet that dark matter is real, visible through its own gamma rays. (CREDIT: ESA/Gaia/DPAC; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

For nearly a century, something unseen has tugged at the cosmos. In the 1930s, Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky noticed galaxies in the Coma Cluster moving as if they carried far more mass than telescopes could detect. That missing weight earned a name you now hear often: dark matter. Scientists think it makes up most matter in the universe, yet no camera has ever caught it directly.

Now you face a new clue. A long sweep through 15 years of NASA satellite data has revealed a faint, odd glow surrounding your home galaxy. The light does not match any known source. Its shape and energy point to a bold idea: dark matter particles may be destroying one another, releasing a soft halo of gamma rays around the Milky Way.

Using data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, Professor Tomonori Totani of the University of Tokyo says he has identified the exact type of gamma rays expected to be produced when hypothetical dark matter particles destroy each other. Fermi does not see stars or clouds. It tracks gamma rays, the most energetic form of light, born in cosmic blasts near black holes, exploding stars, and storms of high-speed particles.

Dark matter, though invisible, may also glow in gamma rays when its particles meet and vanish. Researchers have hunted that signal for years, mostly toward the bright core of the galaxy. But the center is crowded with energetic sources that muddy the view.

This time, scientists took another path. They looked out to the galaxy’s wide halo and away from the thick, busy disk. The hope was simple: the signal would be faint but clearer in the quiet.

A patient search in deep space

The team studied data from August 2008 to August 2023 and focused on very energetic light, from just above 1 billion electron volts to more than 800 billion. Lower-energy light was excluded because the telescope’s aim wobbles there.

They divided the sky into large squares and built a careful picture of every known source of gamma rays. Their model included individual stars and galaxies, cosmic rays hitting gas clouds, background light from across the universe, the giant “Fermi bubbles” that loom above and below the galaxy, and Loop I, a vast structure linked to ancient supernovae.

Each known source became a layer in a giant map. Then the team asked a daring question: What if one more layer followed the shape scientists expect for a dark matter halo?

To test it, they used several ways to describe how dark matter might spread through the galaxy. One common model predicts a smooth cloud that thickens toward the center and thins with distance. They tried versions that assumed dark matter destroys itself, forms clumps, or slowly decays.

A signal at 20 billion electron volts

The result stood out. A bump in gamma rays appeared near 20 billion electron volts across much of the halo. The signal was strong, far beyond what chance alone would produce. It was not there at low energies and faded at very high ones. It rose and fell in a narrow band.

That pattern matters. Most cosmic sources create broad, steady slopes across energy. This glow did not. It peaked.

The shape in the sky mattered too. The light wrapped around the galaxy almost evenly, like a shell. That is what you would expect if dark matter forms a vast, round cloud around the Milky Way.

Of the tested models, one stood out. The best fit came from a version where gamma-ray brightness rises with the square of dark matter density. Other versions did worse. Some even predicted negative light, a clear sign they could not describe reality.

The team then split the sky into chunks and ran the test again. Each region showed the same peak near 20 billion electron volts. The glow was not local. It was galactic.

Could it be something else?

The researchers did not stop there. They tried to make the glow vanish.

The researchers changed how they estimated star birth, the spread of gas, and the energy field across the galaxy. They swapped in alternate background models used by the Fermi team and removed known point sources. The signal held.

They also tested whether fast electrons could be hitting starlight and boosting it into gamma rays, a common process called inverse Compton scattering. That glow usually hugs the galaxy’s disk. This one did not. To explain it that way, the pattern would need to twist sharply with energy, which does not match what scientists know.

After months of checks, the team found no familiar process that fit both the energy and the shape. An unknown source could still exist. But dark matter rose to the top as the cleanest answer.

What kind of particle might it be?

If dark matter causes the glow, what does it reveal about the particle itself?

The best matches came when researchers assumed dark matter breaks into heavy, ordinary particles such as bottom quarks or W bosons, which then decay and make gamma rays. That would place the dark matter particle at roughly 400 to 800 billion electron volts, hundreds of times heavier than a proton.

The needed rate of destruction is higher than some simple models predict. But the team points out a big unknown: how much dark matter surrounds the Sun. Estimates vary widely. A denser local cloud would need fewer collisions to make the glow you see. The true shape of the halo also adds uncertainty.

If the light came from slow decay instead of self-destruction, the particles would need lifetimes trillions of times longer than the age of the universe.

Not the same as the galaxy’s core mystery

You may recall another puzzle closer to home. For years, scientists have debated a gamma-ray glow near the center of the Milky Way that peaks at much lower energy.

This halo signal is different. It spreads wider, peaks higher, and follows a flatter shape in space. The team argues the two glows are likely separate stories. The central one could come from dense packs of spinning neutron stars. The halo one may point to dark matter.

What comes next

This is not proof. It is a powerful hint.

If dark matter causes the glow, you should see echoes elsewhere. Dwarf galaxies that orbit the Milky Way are good places to look. They hold plenty of dark matter and few stars. Small signals have already appeared in some, but nothing decisive.

Future space missions and ground-based observatories that study even more energetic light could confirm or refute the signal. Searches for neutrinos could help too. Dark matter should make those ghostly particles along with gamma rays.

Fritz Zwicky saw a problem in galaxy motion nearly a century ago. Today, you may be seeing its outline in light no eye can catch. The Milky Way’s faint halo does not roar. It whispers. Yet it may be the clearest hint so far that the invisible scaffolding of the universe is beginning to glow.

Practical Implications of the Research

If the glow truly comes from dark matter, science gains a new probe of the universe’s hidden mass. Researchers could map the Milky Way’s dark matter cloud and test theories about how galaxies form and evolve.

Particle physicists would gain clues about a new kind of matter beyond today’s standard model, shaping the hunt for new particles in labs on Earth.

Over time, a clearer picture of dark matter could sharpen models of cosmic growth and help explain why galaxies look the way they do.

Research findings are available online in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics.

Related Stories

- New quantum sensors aim to detect hidden forces behind dark matter

- Dark matter obeys the same cosmic rules as ordinary matter, study finds

- Pulsars or dark matter? The Milky Way’s central glow just got more puzzling

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.