Air-powered soft robots think, sense and move with no electronics

Oxford engineers build air powered soft robots that move, sense and coordinate without electronics, pointing to a new era of embodied intelligence.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

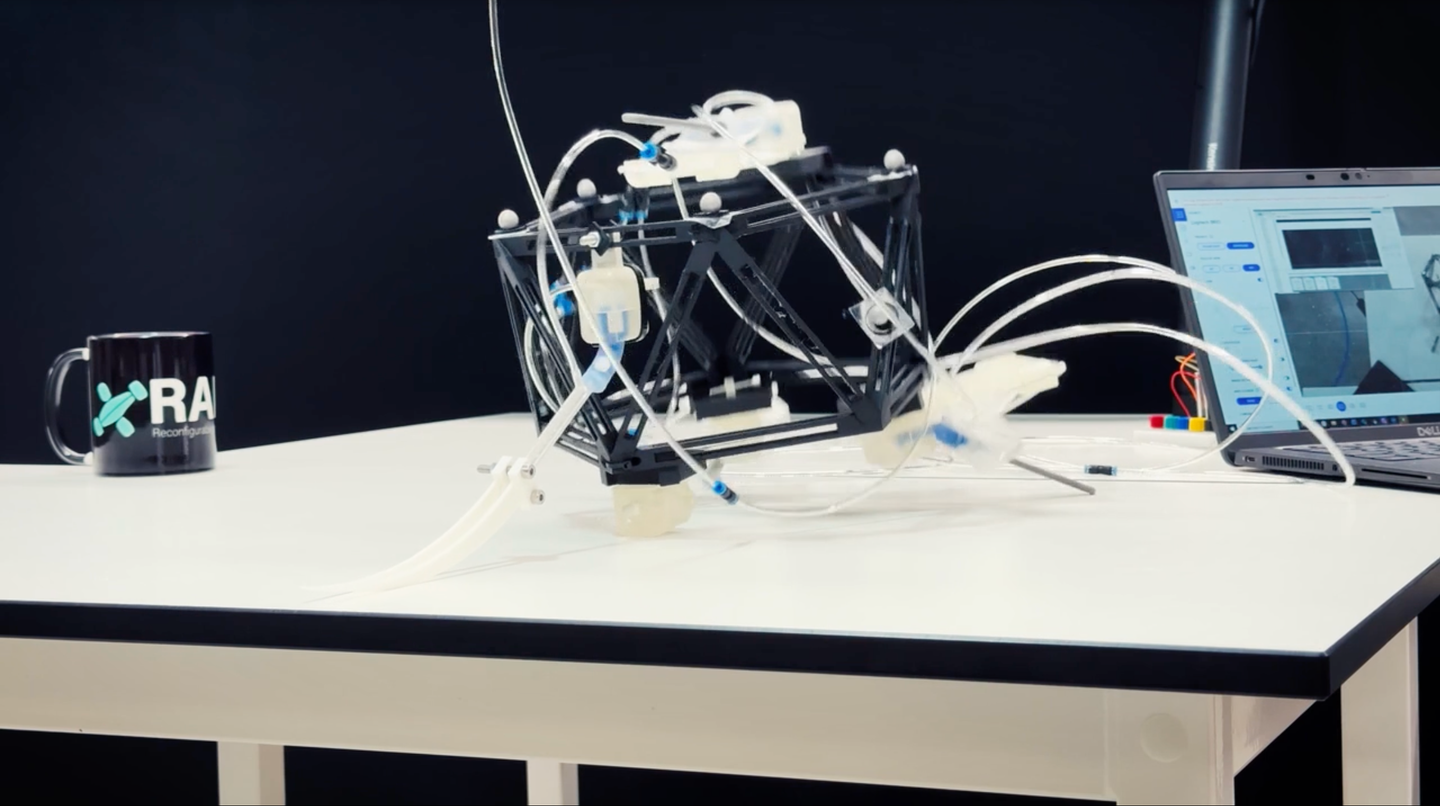

In a new study, Oxford engineers unveil air powered soft robots built from modular fluidic units. These brain free machines can hop, crawl, sort objects and avoid edges without electronics or software, hinting at a future where robot bodies handle much of the thinking. (CREDIT: Antonio Forte and Mostafa Mousa.)

Robots that move, sense and even coordinate with one another usually bring to mind tangled wires, circuit boards and humming motors. In a new study from the University of Oxford, all of that disappears. Instead, soft machines built from rubbery parts and air tubes come to life using only air pressure and clever design, with no electronics or software at all.

These soft “fluidic robots” are described in the journal Advanced Materials. They can hop, crawl, shake and sort objects. They can even fall into a shared rhythm, like a tiny mechanical flock, without a central controller.

Professor Antonio Forte, who leads the Robotic and Additive Design Laboratory (RADLab) at Oxford, put it simply: “We are excited to see that brain-less machines can spontaneously generate complex behaviours, decentralising functional tasks to the peripheries and freeing up resources for more intelligent tasks.”

How Air Powered Soft Robots Work

Soft robots rely on flexible bodies instead of rigid frames. That makes them good at gripping fragile items, squeezing through tight gaps or adapting to rough ground. A long standing goal in this field is to build robots whose bodies handle much of the “thinking” for them, so that behaviour comes from structure and physics, not just code.

The Oxford team tackled this by copying a trick that biology uses all the time. In animals, one body part often handles several jobs at once. A limb can support weight, sense pressure and help control movement, all without a brain telling it what to do at every moment.

To mirror that, the researchers designed a small modular block that runs on air. Each unit is only a few centimetres wide. Depending on how you connect it, the same block can act like a muscle, a pressure sensor or a valve that switches air on and off.

Those units are like a box of identical building bricks. By snapping several together, the team assembled tabletop robots about the size of a shoebox that could hop in place, shake a platform or crawl forward. The hardware stayed the same; only the way the pieces linked together changed.

From Simple Units to Shared Rhythm

When the team pushed the design further, something striking happened. In one particular setup, a single unit began to produce its own rhythm. With a steady supply of air, it inflated and deflated in a repeating cycle; it behaved like an air powered muscle that beats on its own.

Link several of those self oscillating blocks together as legs on the same frame and their motions start to interact through the body and the ground. The shape of the frame, combined with friction and contact with the surface, lets each leg subtly tug on the others.

Lead author Dr Mostafa Mousa explained what the team saw: “This spontaneous coordination requires no predetermined instructions but arises purely from the way the units are coupled to each other and upon their interaction with the environment.”

To make sense of this, the researchers turned to the Kuramoto model, a well known mathematical tool used to describe how oscillators synchronize. It has been used to study metronomes that fall into step or fireflies that end up flashing in unison. Here, the oscillators are air powered legs, and the “communication” happens through mechanical forces instead of light or sound.

When all the pieces are working together, each leg affects the others through shared compression, rebound and friction with the ground. That feedback pulls their rhythms into alignment. The result is coordinated motion with no electronic timing signal at all.

Robots That Sense and React Without Software

Coordination alone would already be impressive, but the same air powered units can also support simple decision making. Because each block can sense and switch air flow as well as move, you can build basic logic directly out of the hardware.

"Our team showed this with a shaker robot that sorted beads. Mounted on a rotating platform, the soft limbs shook in a controlled pattern. That motion nudged beads of different sizes into different containers. All of it was set by the physical layout of the air channels and moving parts; no computer told the robot how to shake," Forte said to The Brighter Side of News.

In another demo, a crawling robot approached the edge of a table. One unit acted as a contact sensor, another handled the air supply, and the rest drove the legs. As long as the front sensor felt the table under it, air kept flowing and the robot inched forward. When the sensor no longer touched the surface, the change in pressure triggered the valve to cut off the air. The robot stopped before tumbling off the edge.

In that moment, you can see how the mechanical system carries out an “if then” decision. If there is ground, keep going; if not, stop. That rule lives in plastic, rubber and air paths, not in a microchip.

Toward Embodied Intelligence In Extreme Places

For the researchers, these results mark a step toward embodied intelligence, where a robot’s body and environment hold much of its control logic. Professor Forte sees this as a shift in how people think about machines.

“Encoding decision-making and behaviour directly into the robot’s physical structure could lead to adaptive, responsive machines that don’t need software to ‘think.’ It is a shift from ‘robots with brains’ to ‘robots that are their own brains.’ That makes them faster, more efficient, and potentially better at interacting with unpredictable environments.”

The current prototypes sit comfortably on a lab bench, but the ideas behind them do not depend on size. In principle, similar designs could be scaled up or reshaped for other tasks. The team now plans to study how to turn these air powered systems into untethered walkers and crawlers that carry their own compact air supply.

Long term, soft robots that run, sense and coordinate using only air and simple materials could be valuable in places where electronics struggle. Think about extreme heat, high radiation or wet, dirty conditions where computer parts fail quickly and replacement is costly. In those places, a body that “thinks” through physics rather than fragile chips could be a real advantage.

Research findings are available online in the journal Advanced Materials.

Related Stories

- Scientists use light-controlled nanorobots to quickly grow bone cells

- New AI-powered armband uses gestures to control robots in real time

- Scientists combine magnetic microrobots with ultrasound stimulation to grow new neurons

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer