Alaknanda: Ancient spiral galaxy challenges existing knowledge of cosmic evolution

Astronomers discover a mature spiral galaxy just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, challenging theories of galaxy formation.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

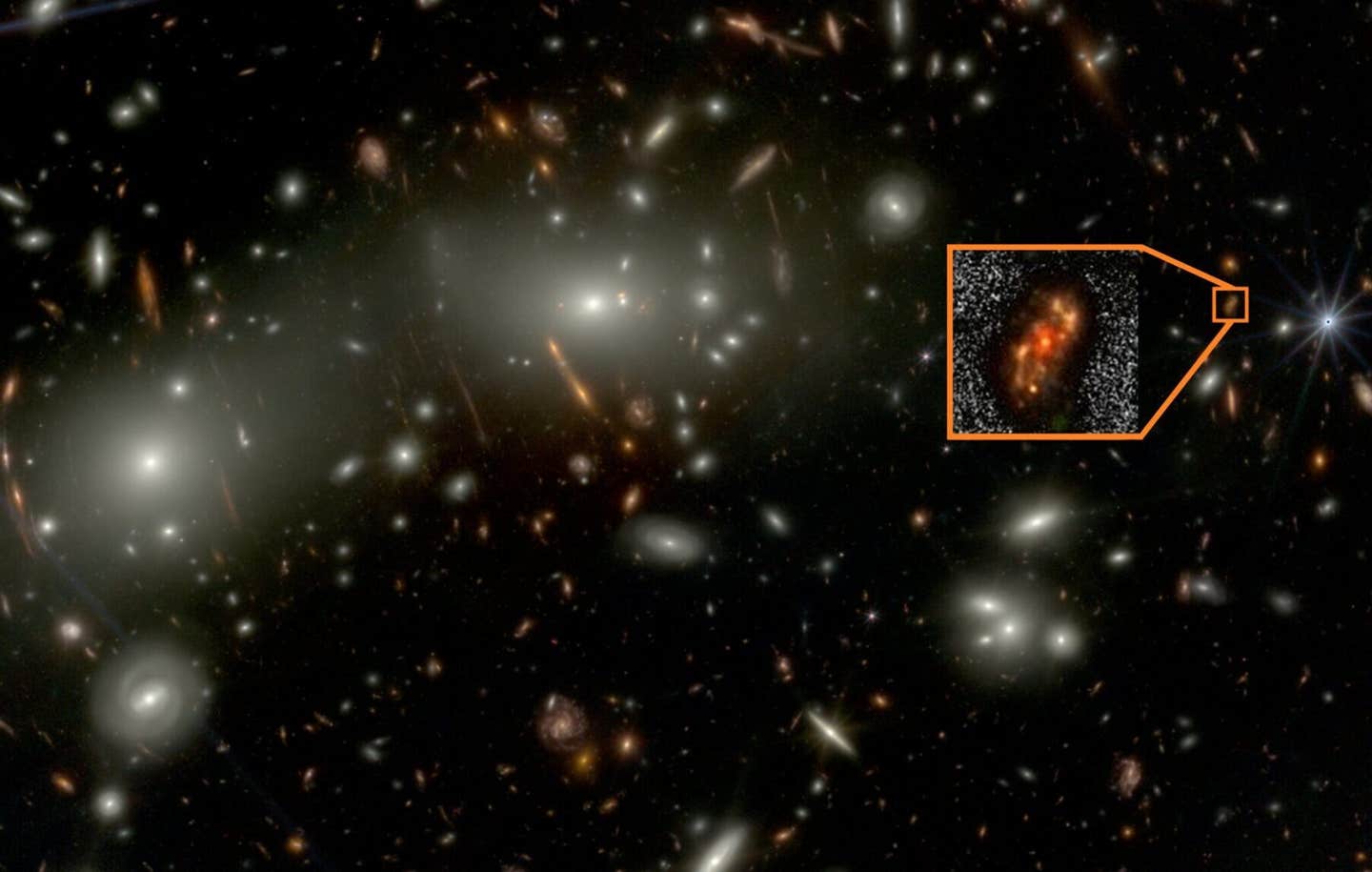

The newly identified spiral galaxy Alaknanda, shown in the inset, appears in shorter-wavelength observations from the James Webb Space Telescope. Bright foreground galaxies from the Abell 2744 cluster are also visible in the same field. (CREDIT: NASA/ESA/CSA, I. Labbe/R. Bezanson/Alyssa Pagan (STScI), Rashi Jain/Yogesh Wadadekar (NCRA-TIFR))

Early in the story of the universe, long before galaxies like the Milky Way were expected to take shape, astronomers have now identified a system that already looks strikingly familiar. Researchers at the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Pune, India, using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope, have spotted a massive spiral galaxy that appears fully formed just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

The galaxy, named Alaknanda, was discovered by Rashi Jain and Yogesh Wadadekar and reported in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics. Its name comes from a Himalayan river and echoes the Hindi name for the Milky Way. The comparison is not poetic alone. Alaknanda shows a bright central bulge, a wide rotating disk, and two clear spiral arms, features long thought to require billions of years to emerge.

You are seeing this galaxy at a redshift of about 4, meaning its light began its journey when the universe was still in its infancy. Yet its structure resembles that of nearby spiral galaxies that formed much later. This unexpected maturity places Alaknanda among the most compelling challenges yet to standard ideas about how galaxies grow.

Finding order where chaos was expected

Astronomers have long believed that the early universe should have been dominated by messy, irregular galaxies. Gas was turbulent, mergers were frequent, and disks were thought to be unstable. Under those conditions, neat spiral patterns seemed unlikely.

Alaknanda does not fit that picture. It is actively forming stars at a rate of roughly 60 solar masses per year, about 20 times faster than the present-day Milky Way. It already contains close to ten billion solar masses worth of stars. About half of that stellar mass appears to have formed within just 200 million years.

“Alaknanda has the structural maturity we associate with galaxies that are billions of years older,” Jain said. “Finding such a well-organised spiral disk at this epoch tells us that the physical processes driving galaxy formation can operate far more efficiently than current models predict.”

This single galaxy does not overturn theory by itself. Still, it adds to growing evidence from Webb that some massive galaxies settled into orderly disks far earlier than expected.

A cosmic magnifying glass

Alaknanda was identified in observations of the massive galaxy cluster Abell 2744, also known as Pandora’s Cluster. The cluster’s immense gravity bends and magnifies light from more distant galaxies behind it, a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. That effect made Alaknanda appear brighter and larger, allowing astronomers to resolve its spiral structure in unusual detail.

The discovery came from the UNCOVER survey, which combines deep imaging and spectroscopy from Webb and Hubble. The team analyzed images taken through more than 20 different filters, spanning ultraviolet to near-infrared wavelengths. This broad coverage allowed them to separate starlight from glowing gas and to estimate the galaxy’s distance, mass, dust content, and star formation history with high confidence.

In survey catalogs, Alaknanda stands out as the only galaxy between redshifts 3 and 6 that clearly shows a classic two-armed, or grand-design, spiral pattern.

Measuring its physical properties

"To determine Alaknanda’s characteristics, our research team modeled its light using established galaxy analysis tools. These models place the galaxy securely at a redshift near 4, consistent with strong spectral features such as the Lyman break and emission from ionized oxygen and hydrogen," Rashi Jain told The Brighter Side of News.

"The results paint a picture of a lively, growing system rather than a fading one. The galaxy’s stars are relatively young, with a mass-weighted age of about 200 million years. Star formation likely began less than a billion years after the Big Bang. Dust is present but not overwhelming, suggesting that much of the galaxy’s light still escapes into space," he continued.

In physical size, Alaknanda spans roughly 30,000 light-years, comparable to the Milky Way’s disk. That scale alone is striking for such an early time.

A settled disk with spiral arms

High-resolution images show that Alaknanda is dominated by its disk, not its central bulge. Detailed modeling reveals that only about 15 percent of its visible light comes from the bulge, with the rest spread across the disk and spiral arms. Those arms appear across many wavelengths and are dotted with bright knots of star formation, creating a beads-on-a-string appearance.

Nonparametric measures of its shape also point to a stable disk rather than a recent merger. Together, these indicators suggest a galaxy that has avoided major disruptive collisions, at least in the recent past.

A small companion galaxy lies close by and shares a nearly identical distance. This neighbor could be interacting with Alaknanda and may even play a role in shaping its spiral pattern.

Rethinking how spirals form

How did such a well-organized spiral arise so early? Astronomers are still debating the answer. One possibility is steady inflow of cold gas, allowing the disk to settle and develop spiral waves naturally. Another is a tidal interaction with the nearby companion, which can trigger spiral arms, though such features often fade quickly.

A bar-driven origin seems less likely, as images show no clear central bar. Major mergers also appear unlikely, since those typically produce bulge-heavy systems, not disk-dominated ones like Alaknanda.

“Alaknanda reveals that the early Universe was capable of far more rapid galaxy assembly than we anticipated,” Wadadekar said. “Somehow, this galaxy managed to organise itself extraordinarily fast by cosmic standards.”

Future observations with Webb’s spectroscopic instruments or with the Atacama Large Millimeter Array in Chile could measure how gas and stars move within the disk. Those data may reveal whether the galaxy is dynamically calm or still turbulent beneath its graceful appearance.

Practical Implications of the Research

Alaknanda’s discovery reshapes how you can think about the early universe. If galaxies could assemble, settle, and form spiral arms so quickly, then the timeline of cosmic structure formation needs revision. This affects models of how stars, planets, and chemical elements built up over time.

For researchers, the finding pushes simulations to account for faster disk formation and greater early stability. For humanity, it deepens understanding of cosmic origins and suggests that environments capable of supporting complex structures, including those that eventually lead to planets, may have appeared earlier than once believed.

Research findings are available online in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Related Stories

- Most distant spiral galaxy ever found shatters theories of cosmic formation

- Astronomers reveal how the Milky Way’s violent youth forged a calmer spiral giant

- Distant galaxy’s black hole offers extraordinary glimpse into the Milky Way's future

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.