Ancient Iraqi city provides rare insight into daily life in Mesopotamia

Rare clay tablets, luxury pottery, and palace ruins found in northern Iraq may prove Kurd Qaburstan was a major Bronze Age power.

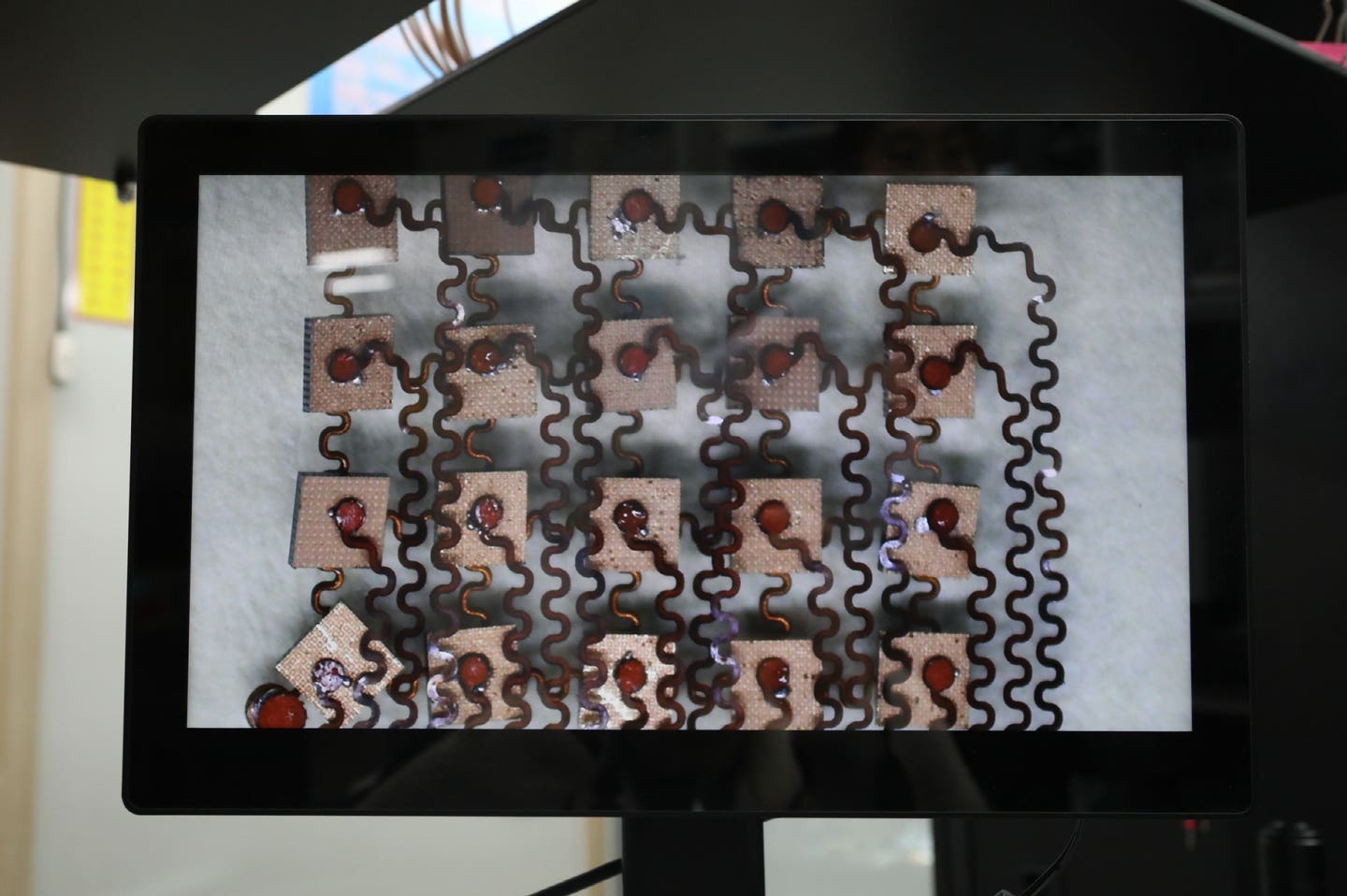

New finds at Kurd Qaburstan in Iraq may reveal secrets of a forgotten Mesopotamian city and change what we know about the Bronze Age. (CREDIT: Tiffany Early-Spadoni)

Archaeologists working at a long-buried city in northern Iraq have unearthed clues that could rewrite part of Mesopotamia’s hidden story. The site, Kurd Qaburstan, sits in the Erbil region and may have once been the powerful city of Qabra, referenced in ancient Babylonian records. During a recent excavation season, researchers found rare clay tablets with cuneiform writing, a game board, and parts of a large administrative building. These discoveries open a new window into everyday life in a part of Mesopotamia that historians have often overlooked.

The team behind this major discovery includes Tiffany Earley-Spadoni, a University of Central Florida historian, and a group of international scholars. Their goal is not only to find artifacts, but to understand how people lived, worked, and survived around 1800 BCE—the Middle Bronze Age.

Exploring a Lost Civilization

Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, is often called the cradle of civilization. Many people know about its southern cities like Uruk, where some of the earliest writing systems developed. But northern cities, especially those near modern-day Erbil, remain largely unknown. That’s what makes this site so valuable.

“We know quite a bit about Mesopotamian cities in the south,” says Earley-Spadoni. “We seek to fill in this gap in the scholarship by investigating a large urban site, one of the few that's ever been investigated in northern Iraq.”

Her team began working at Kurd Qaburstan in 2013 and have made steady progress, with their most recent dig taking place from May to July 2024. The research receives support from the U.S. National Science Foundation and cooperation from the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

The site has revealed not just grand buildings but signs of ordinary life. In the northwest part of the city, archaeologists found courtyards, clay drainpipes, and piles of household trash. They dug up well-made pottery—cups, bowls, plates, and jars—some with fine decorations. These weren’t just scraps. The objects suggest that at least some residents had a good standard of living.

Animal bones found alongside the pottery tell another part of the story. People in this neighborhood likely ate a diet that included both farm-raised meat and wild animals. For a non-elite part of town, that’s surprising. It hints that life here might have been more equal than previously thought.

Related Stories

“We’re studying this ancient city to learn very specific things about the ancient inhabitants,” says Earley-Spadoni. “Were there very poor people and very rich people? Or was there possibly a middle class?”

Digging Into History

The other focus of the excavation was in a section of the lower city, where the team uncovered what appears to be an administrative complex or palace. Researchers had guessed its location based on clues from earlier surveys, including a 2022 geophysical scan using magnetometry. This technology lets archaeologists “see” underground without digging, guiding their efforts more accurately.

Once they began digging, the team found massive stone walls and hints of a large public structure. They also found human remains and signs of destruction. These may point to a violent event, such as a battle or invasion.

Even more compelling were the clay tablets written in cuneiform—the wedge-shaped script used across Mesopotamia. These are the first tablets of their kind found in the region and hold great promise.

“The first of the three tablets was discovered in a trash-filled deposit along with building rubble and human remains,” Earley-Spadoni says. “Its context suggests dramatic events, possibly evidence of ancient warfare.”

The tablets are still being translated. But even early results give researchers hope. They show personal names, writing styles, and word choices that can reveal literacy levels and cultural identity. Scholars may be able to trace how this city interacted with its neighbors and how its people saw themselves.

Rediscovering Qabra?

The most exciting theory is that this site may actually be the lost city of Qabra. Ancient texts, including the famous Stele of Dadusha from the Old Babylonian period, describe Qabra as a key regional power. If Kurd Qaburstan is Qabra, then these ruins once belonged to a major center of politics, trade, and culture.

“There are ample signs pointing to Kurd Qaburstan serving as a major regional administrative hub,” Earley-Spadoni says. “The presence of writing, monumental architecture, and other administrative artifacts in the lower town palace further supports this identification.”

If proven true, this would boost the site’s historical value and fill a major gap in our knowledge of Middle Bronze Age Mesopotamia. It would also help historians move beyond the usual focus on southern Mesopotamia, bringing new voices and stories to light.

“We hope to find even more historical records that will help us tell the story of [the city] from the perspective of its own people rather than relying only on accounts written by their enemies,” says Earley-Spadoni.

A Broader Legacy

Unlike many digs that focus on royal tombs or grand temples, this project looks at city life from the ground up. It’s about more than just kings and palaces. The researchers want to know how the city grew—was it carefully planned, or did it grow naturally? Who held power? What was life like for the average person?

“The focus of the research is the organization of ancient cities, and it's specifically the organization of Kurd Qaburstan,” Earley-Spadoni explains. “This is about that same time almost 4,000 years ago [as Hammurabi’s law code]. We decided that this would be an interesting place to investigate what it was like to be an everyday person at a city during the Middle Bronze Age, which has been an understudied topic.”

Findings from the site suggest a more complex society than previously thought, where class lines may have been more flexible and wealth more widely shared. The evidence challenges older views that divided ancient cities sharply between rich elites and poor commoners.

By analyzing trash heaps, kitchen pottery, bones, and broken tablets, Earley-Spadoni and her team are building a fuller picture of what life was really like in this ancient place.

Looking Ahead

The story of Kurd Qaburstan is far from complete. More excavation seasons are planned, and more tablets may still lie buried. Each discovery adds another piece to the puzzle, helping historians better understand a city and time that have long remained in the shadows.

“The Middle Bronze Age in northern Iraq is poorly understood due to limited prior research and the inherent biases of the available historical sources,” says Earley-Spadoni.

Her team’s work continues to bring new clarity to a past that shaped so much of today’s world. From written laws to planned cities, many aspects of modern life began in Mesopotamia. Now, thanks to these efforts, people in the north are finally getting their place in that grand story.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.