Antarctica’s buried landscape may be slowing climate change, study finds

Radar scans reveal hidden river-carved landscapes beneath East Antarctica. These ancient plains may slow ice loss and refine sea level predictions.

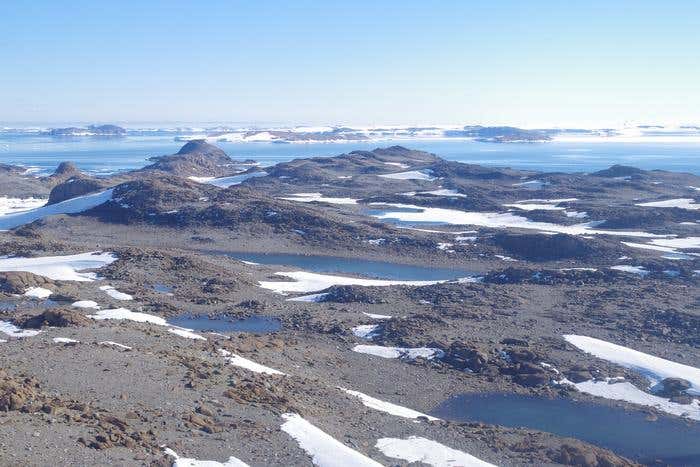

Ancient river plains found beneath East Antarctica may reveal how fast ice could melt and raise sea levels in a warmer world. (CREDIT: David Small)

Hidden beneath the thick, frozen skin of East Antarctica lies a surprising discovery—ancient river-carved landscapes that may hold the key to understanding how the vast ice sheet will behave as the world continues to warm.

By using radar to look through the ice, researchers from Durham University uncovered wide, flat surfaces buried deep beneath a 3,500-kilometer stretch of East Antarctica’s coast. These surfaces, though now fragmented and separated by deep valleys, were once part of a giant coastal plain shaped by rivers that flowed freely across the land. This plain likely formed after East Antarctica split from Australia around 80 million years ago and before ice began to blanket the continent roughly 34 million years ago.

These findings, published in Nature Geoscience, could change how scientists predict the future of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. The radar images show that, although the ice has advanced and retreated many times since it first formed, some ancient landforms have remained surprisingly untouched. These surfaces reveal more than just a long-lost landscape. They also offer clues about how the ice has behaved for millions of years—and how it might behave in the future.

A Lost World Beneath the Ice

Led by Dr. Guy Paxman, the team used radio-echo sounding to map the bedrock beneath the ice between Princess Elizabeth Land and George V Land. These radar images revealed something unexpected: large flat areas, now lying hundreds of meters below sea level once corrected for the weight of the ice. These areas are gently tilted toward the sea and appear again and again along the coast.

“The landscape hidden beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is one of the most mysterious not just on Earth, but on any terrestrial planet in the solar system,” said Dr. Paxman. He noted that these flat features became clear once the team began examining the radar data. “The flat surfaces we have found have managed to survive relatively intact for over 30 million years, indicating that parts of the ice sheet have preserved rather than eroded the landscape.”

That’s a striking contrast to what scientists might expect. Ice sheets usually grind away the land beneath them, especially where they move quickly. But here, much of the ancient surface has survived nearly untouched.

Related Stories

- Antarctica's melting ice sheets may trigger massive volcanic activity

- Drone Technology Exposes Alarming Changes in Greenland Ice Sheet

- Satellites deliver first picture of Greenland Ice Sheet melting

How Ancient Rivers Shaped Today’s Ice Sheet

The research suggests these flat zones were carved by rivers between the time when East Antarctica split from Australia—about 100 to 80 million years ago—and the moment when permanent ice took over around 34 million years ago. At that time, the landscape was likely much warmer and free of ice.

Then, as Antarctica froze, ice began to flow through older river valleys and tectonic cracks, avoiding the higher, flatter areas. This pattern of flow shaped the deep troughs between the preserved flat surfaces and continues to direct glaciers today.

According to co-author Professor Neil Ross of Newcastle University, this discovery helps connect scattered clues from earlier studies. “We’ve long been intrigued and puzzled about fragments of evidence for ‘flat’ landscapes beneath the Antarctic ice sheets,” he said. “This study brings the jigsaw pieces of data together, to reveal the big picture: how these ancient surfaces formed, their role in determining the present-day flow of the ice, and their possible influence on how the East Antarctic Ice Sheet will evolve in a warming world.”

Because fast-moving glaciers travel through the valleys, the ice above these flat surfaces is relatively still. That stability plays an important role in how quickly ice might be lost in the future.

A Barrier Against Rapid Ice Loss

Antarctica is already losing ice due to rising temperatures. But these preserved land surfaces may be acting like a brake. They slow the movement of the ice, creating a more stable margin along parts of East Antarctica’s coast. This has major implications.

If the East Antarctic Ice Sheet melted completely, global sea levels would rise by as much as 52 meters. While that level of melt is not expected anytime soon, even small changes in how quickly ice moves into the ocean can matter. Understanding what’s going on beneath the surface helps scientists improve predictions about the future.

Dr. Paxman emphasized that the shape and position of these ancient features are vital. “Information such as the shape and geology of the newly mapped surfaces will help improve our understanding of how ice flows at the edge of East Antarctica,” he explained. “This in turn will help make it easier to predict how the East Antarctic Ice Sheet could affect sea levels under different levels of climate warming in the future.”

A New Piece of the Climate Puzzle

Adding these hidden surfaces into ice sheet models could lead to more accurate forecasts. As warming continues, researchers need better ways to predict which parts of Antarctica are most at risk. These flat surfaces may provide stability now, but it’s unclear how long that will last.

The next step will be to drill down through the ice and take samples from the rock below. By analyzing when these surfaces were last free from ice, scientists hope to learn more about how the ice sheet behaved during past warm periods. That could show how it might respond to warming oceans and air in the future.

These efforts could help solve one of the biggest climate questions of our time: how quickly the Antarctic ice sheet will melt—and how high sea levels could rise as a result.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.