Asteroid Bennu samples reveal ancient water offering new clues about the origin of life on Earth

NASA finds amino acids and DNA letters in Bennu samples, showing water helped craft life’s ingredients in space.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

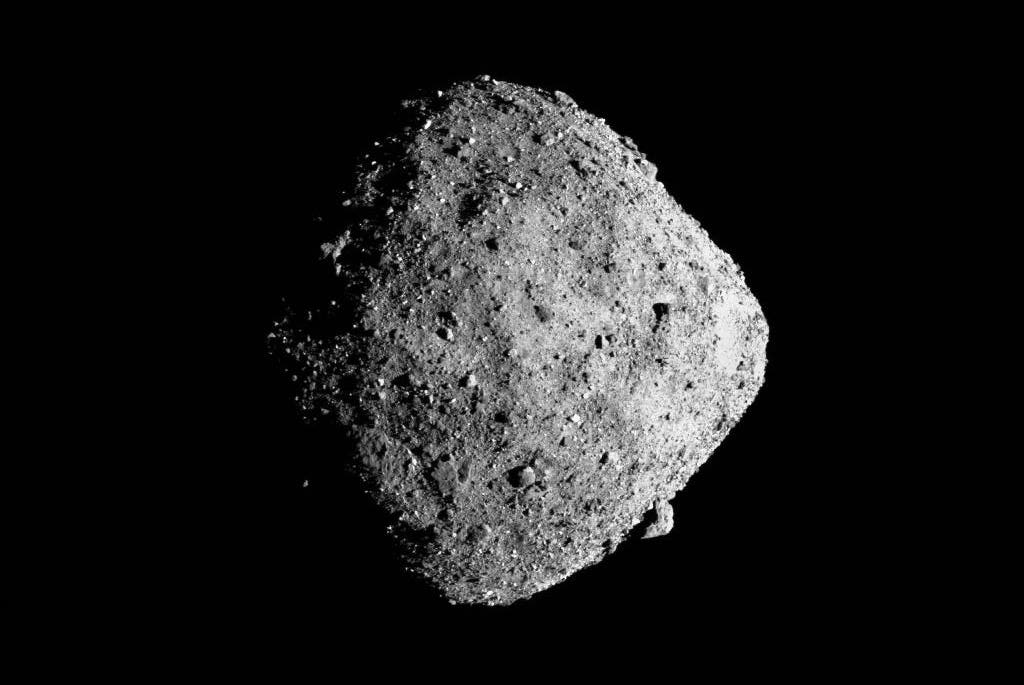

Pristine samples from asteroid Bennu reveal amino acids and DNA building blocks, pointing to watery chemistry that could seed life. (CREDIT: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona)

Some of the oldest objects in the solar system still drift above your head. Asteroids and comets formed before Earth took shape, and they carry a record of a chemical world that existed long before life. When pieces fall as meteorites, scientists sometimes find amino acids and nucleobases, the same kinds of molecules your body uses to build proteins and store genetic code. For decades, that raised a simple question with a big reach: did space deliver some of life’s ingredients to Earth?

On Sept. 24, 2023, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft delivered a clearer answer. It returned sealed samples from the near-Earth asteroid Bennu, untouched by Earth’s air, water or microbes. Unlike meteorites that land at random and pick up contamination, these grains were grabbed from a known spot and locked away in space. They are as close as scientists can get to time capsules from the birth of the solar system.

A new analysis, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reads like a lab report from deep time. Inside Bennu’s dust, researchers identified many of the basic molecules life relies on, including a wide range of amino acids and all five nucleobases found in DNA and RNA. In the same tiny samples, they also traced the marks of ancient liquid water that rewrote the chemistry inside Bennu’s parent body.

The chemistry of ancient water

Bennu is a rubble pile asteroid, a loose collection of fragments from a larger world that shattered long ago and slowly reassembled. Those chunks came from different depths inside the original body, and they carry different stories. Some stones are angular, others rounded or mottled, and each holds a record of how often water once seeped through the rock.

Liquid water leaves fingerprints. It forms clay-like minerals called phyllosilicates, along with magnetite, carbonates and salts. Scientists found all of these in Bennu’s samples. The minerals tell you that the asteroid’s parent body once warmed enough for ice to melt, and that water mixed with rock for long stretches.

Water changes more than minerals. It reshapes organic matter, too. Bennu holds two main forms of carbon-rich material. One is a tough, tar-like network that refuses to dissolve. The other is a small but vital set of loose molecules that includes amino acids and nucleobases. Together, they record how chemistry unfolds inside a wet asteroid.

To read that record, researchers heated tiny grains to high temperatures to release trapped compounds, then ran them through sensitive instruments that sort chemicals by weight and charge. They also treated other grains with a stabilizing solution that protects fragile molecules so they can be measured. The approach let scientists compare different stones from Bennu’s surface and match them to rare meteorites on Earth.

Fingerprints in smoky dust

When the Bennu grains were heated, they released a smoky mix of aromatic compounds, some carrying nitrogen and sulfur, others oxygen. The pattern matched what scientists see in meteorites altered by water. Certain molecules, like alkylated naphthalenes, rise in abundance as water works longer and harder on rock. Those ratios showed that most Bennu stones experienced heavy alteration. One mottled type appeared even more processed, hinting at late bursts of fluid activity.

That smoky signature matters because it mirrors the chemistry found in the wettest meteorites on Earth, known as CI and CM types. It tells you Bennu’s parent body went through a long soaking, enough to rebuild its organic matter from the inside out. Different stones preserved different levels of this change, which now lie side by side in a single asteroid.

Amino acids and DNA letters, together

The most striking results came from the soluble fraction. In a blended sample made from many tiny grains, scientists detected 15 of the 20 standard amino acids life uses to build proteins. They also found all five nucleobases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, thymine and uracil. In addition, they measured extra amino acids and unusual bases that biology does not use today but that reveal how chemistry can wander.

When the team tested stones one by one, the pattern shifted. Less altered rocks held more kinds of amino acids. Heavily altered stones held fewer. The trend fits what scientists have seen in meteorites for years: more water often means a narrower menu, because some molecules break down as others form.

The lab ran blank tests with the same chemicals and glassware. Those controls showed only faint traces of common amino acids and none of the rare ones. That strengthens the case that Bennu’s chemical riches did not hitch a ride from Earth.

One finding stood out. The team tentatively detected tryptophan, an amino acid often tied to living systems and rarely reported in space rocks. If confirmed, it would suggest this molecule can arise without life. It would also explain why it seldom appears in meteorites that blaze through Earth’s atmosphere, because heat can destroy it.

A patchwork world

Bennu’s mix of stones reads like a map of an ancient ocean that never existed. Some fragments point to deep alteration, others to milder soaking. Together, they show that Bennu’s parent body did not follow a single path. Instead, water turned on and off, moved through cracks and pockets, and rewrote chemistry in waves.

This patchwork helps explain why the asteroid carries such a wide set of organics. Some likely formed in the cold clouds between stars. Others took shape later as water and rock reacted in a warm interior. Still others may come from the breakdown of older material. You see all three histories folded into one small world.

What this means for life

The chemistry inside Bennu points to many routes toward life’s toolkit. Simple amino acids can form in watery mixtures with ammonia and cyanide. Aromatic amino acids probably require clay minerals to speed the reactions. Other molecules fit pathways that work best in alkaline, ammonia-rich fluids. The nucleobases may come from sunlight acting on icy grains before the solar system formed, or from reactions inside the asteroid itself.

Five of the standard amino acids were not found, but the study notes that chemistry can build them from others that were present. For example, sulfur-rich waters can turn serine into cysteine. Stepwise reactions can reshape aspartic acid into lysine. The discovery of imidazole compounds is especially important because they can lead to histidine.

Together, the results strengthen a long-held idea. Small, wet worlds can manufacture key parts of life and deliver them through impacts. The samples also serve as a warning. Some molecules, like tryptophan, may appear as signs of life but could arise without it. Future missions must be careful when judging alien chemistry.

Research findings are available online in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Related Stories

- RNA-engineered proteins may explain the birth of life on Earth

- Life on Earth may have come from outer space, study finds

- Microbe discovery reveals ancient clues to how complex life began

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.