Astronomers map the Sun’s shifting atmospheric edge for the first time

Scientists have created the first continuous maps of the Alfvén surface, the boundary where the solar wind escapes the Sun.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

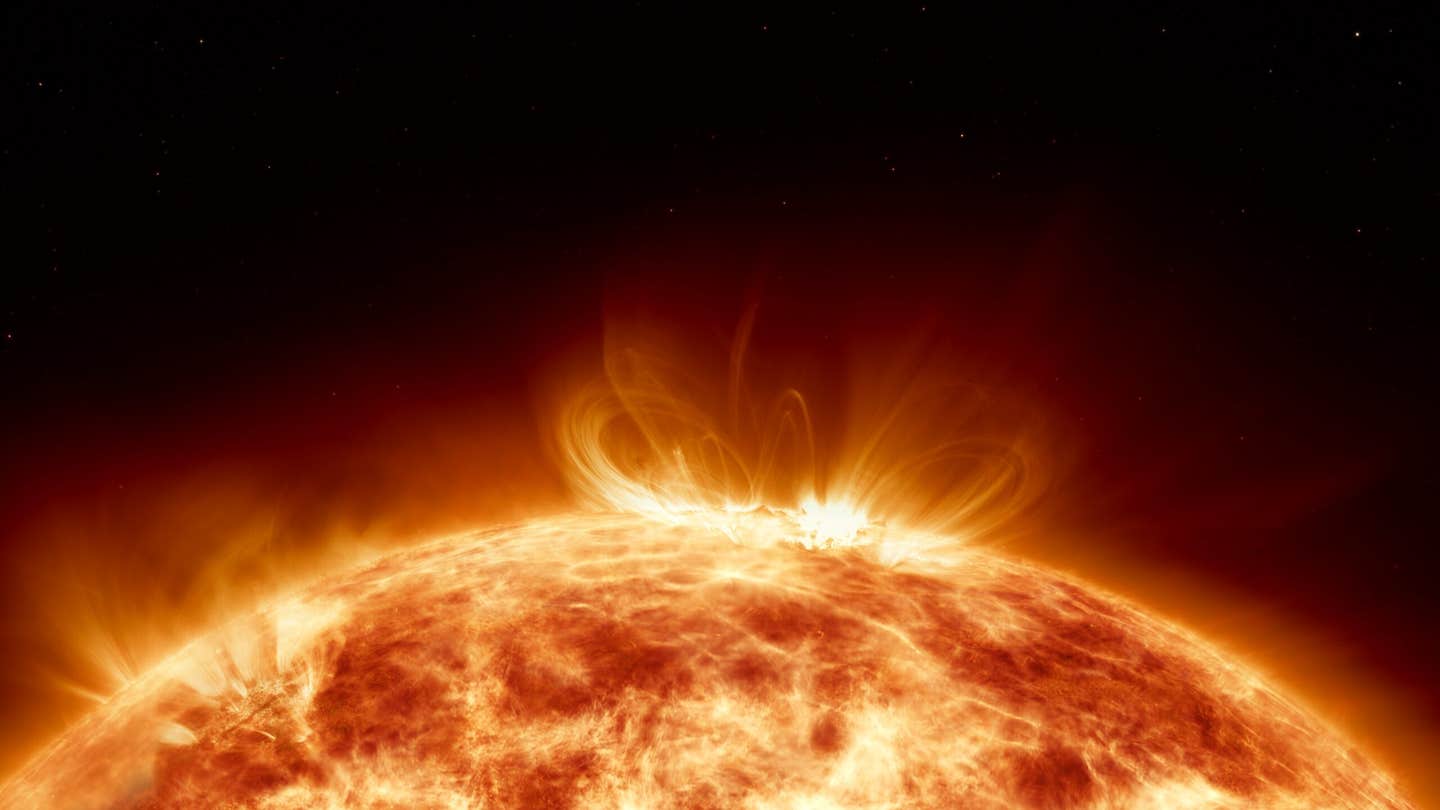

New maps reveal how the Sun’s outer atmospheric boundary grows larger and rougher as solar activity rises. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

Far above the Sun’s bright surface, a steady stream of charged particles accelerates into space. This outflow, known as the solar wind, starts nearly motionless and then races outward at hundreds of kilometers per second. Along the way, it crosses invisible boundaries where physical rules change. One of the most important is the Alfvén surface, the point where the solar wind moves faster than magnetic disturbances can travel.

Inside this boundary, information can still flow back toward the Sun. Outside it, the wind moves too fast, carrying signals away forever. For scientists, this surface marks the effective edge of the Sun’s atmosphere and the birthplace of the solar wind that shapes space around Earth.

Because of its importance, the Alfvén surface became a major target for NASA’s Parker Solar Probe. Before launch, models suggested it sat roughly 10 to 20 solar radii from the Sun, depending on solar activity. In 2021, Parker confirmed those predictions when it crossed the boundary at about 19.8 solar radii.

Now, scientists have gone further. By combining data from multiple spacecraft, they have created the first continuous, two-dimensional maps of how this boundary changes over time.

Turning Sparse Measurements Into a Living Map

The new research draws on data from Parker Solar Probe, ESA’s Solar Orbiter, and several spacecraft near Earth, including Wind, ACE, and DSCOVR. Together, these missions cover distances from just under 10 solar radii to one astronomical unit. The data span October 2018 through April 2025, a period covering the rise and peak of solar cycle 25.

Researchers compiled a uniform set of solar wind measurements, including particle density, speed, temperature, and magnetic field strength. From these, they calculated the Alfvén speed and the Alfvén Mach number, which compares flow speed to magnetic wave speed. All values were averaged over 15-minute intervals, creating a detailed statistical picture of the wind at many distances.

To interpret those measurements, the team built a family of physics-based solar wind models. These models describe how speed, density, and temperature change with distance from the Sun. They include an empirically tuned force that represents the push from Alfvénic fluctuations near the Sun. By adjusting model parameters, the researchers produced 40 profiles that span nearly the full range of observed solar wind conditions.

For each real measurement, they selected the model profile that best matched the observed wind speed and scaled it to the measured magnetic conditions. The point where modeled wind speed equaled Alfvén speed marked the inferred height of the Alfvén surface for that flow.

Testing the Method Against Parker’s Deep Dives

Any indirect method needs validation. Parker Solar Probe provided that test. Using Parker data, the team identified intervals where the Alfvén Mach number hovered near one, clear signs of direct boundary crossings. They then compared those real crossings with heights inferred from their scaling method.

The match was strong. Whether the calculations started from Parker data near the Sun, Solar Orbiter data farther out, or measurements near Earth, the inferred boundary heights closely matched Parker’s direct encounters.

A simpler shortcut method underestimated the boundary height by up to several solar radii. Including solar wind acceleration and mass conservation removed that bias, leaving differences of less than one solar radius between spacecraft. That agreement gave researchers confidence that their approach captures real solar wind behavior.

A Boundary That Grows and Roughens With Activity

With the method confirmed, scientists mapped the Alfvén surface through solar cycle 25. They reconstructed its shape around the Sun using data from different longitudes, building a rotating, equatorial view.

The result is not a smooth shell. Instead, the boundary appears uneven and spiky, with localized bulges extending outward. Some features appear in data from one spacecraft but not others, suggesting short-lived disturbances such as coronal mass ejections.

Two clear trends emerge. As solar activity increases, the average height of the Alfvén surface rises. Early in the cycle, median heights ranged from about 12 to 17 solar radii. Near solar maximum, they climbed to roughly 15 to 23 solar radii. At the same time, the surface became thicker and less spherical. Variations in height increased, tracking higher sunspot numbers and more frequent eruptions.

Why the Boundary Matters

These changes have real physical consequences. The Sun loses angular momentum through the solar wind, and that loss scales with the square of the Alfvén surface height. A modest rise in the boundary can nearly double the torque exerted by the wind. During active periods, the Sun spins down more efficiently.

The structure of the boundary also matters for coronal heating and turbulence. The region near the Alfvén surface may be a preferred site for energy dissipation and particle heating. As the boundary moves outward and becomes more irregular, the volume where these processes occur grows more complex. That places tighter constraints on models of the solar corona.

The findings also matter beyond our Sun. Around more active stars, the Alfvén surface may extend far enough to envelop close-in planets. In those systems, planets remain magnetically connected to their stars, with implications for atmospheres and habitability. The Sun’s own changing boundary offers a nearby test case for understanding those distant systems.

Parker’s Role and What Comes Next

The new maps also place Parker Solar Probe’s journey in context. Early in the mission, its closest passes stayed above the average boundary, dipping below only during brief encounters with outward spikes. As the boundary expanded and Parker’s perihelion shrank, the spacecraft began spending longer periods inside the sub-Alfvénic region.

“With every orbit, Parker Solar Probe is diving deeper into the region where the solar wind is born,” said Michael Stevens, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian and principal investigator of Parker’s SWEAP instrument. “We are now headed for an exciting period where it will witness firsthand how those processes change as the sun goes into the next phase of its activity cycle.”

Sam Badman, an astrophysicist at the same institution and lead author of the study, emphasized the significance of knowing the boundary’s true shape. “Parker Solar Probe data from deep below the Alfvén surface could help answer big questions about the sun’s corona, like why it’s so hot,” Badman said. “But to answer those questions, we first need to know exactly where the boundary is.”

"We believe that future data from Parker and Solar Orbiter will not just refine the map of the Alfvén surface, but also enable scientists to compare in detail how heating, turbulence, and particle acceleration differ on the two sides of this invisible but fundamental boundary," Stevens told the The Brighter Side of News.

The study confirms long-standing predictions about how the boundary changes with solar cycles. It also provides a practical map that scientists can now use to guide future observations.

Research findings are available online in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Related Stories

- Scientists finally explain why the Sun's corona burns millions of degrees hotter than its surface

- New telescope technology reveals Sun’s corona in unmatched detail

- The Sun’s secret role in shaping comet paths and meteor showers

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.