Astronomers spot closest giant planet orbiting binary stars ever observed

Astronomers have confirmed a giant planet orbiting a tightly bound pair of young stars, marking a first in direct exoplanet imaging. The planet, known as HD 143811 AB b, is…

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

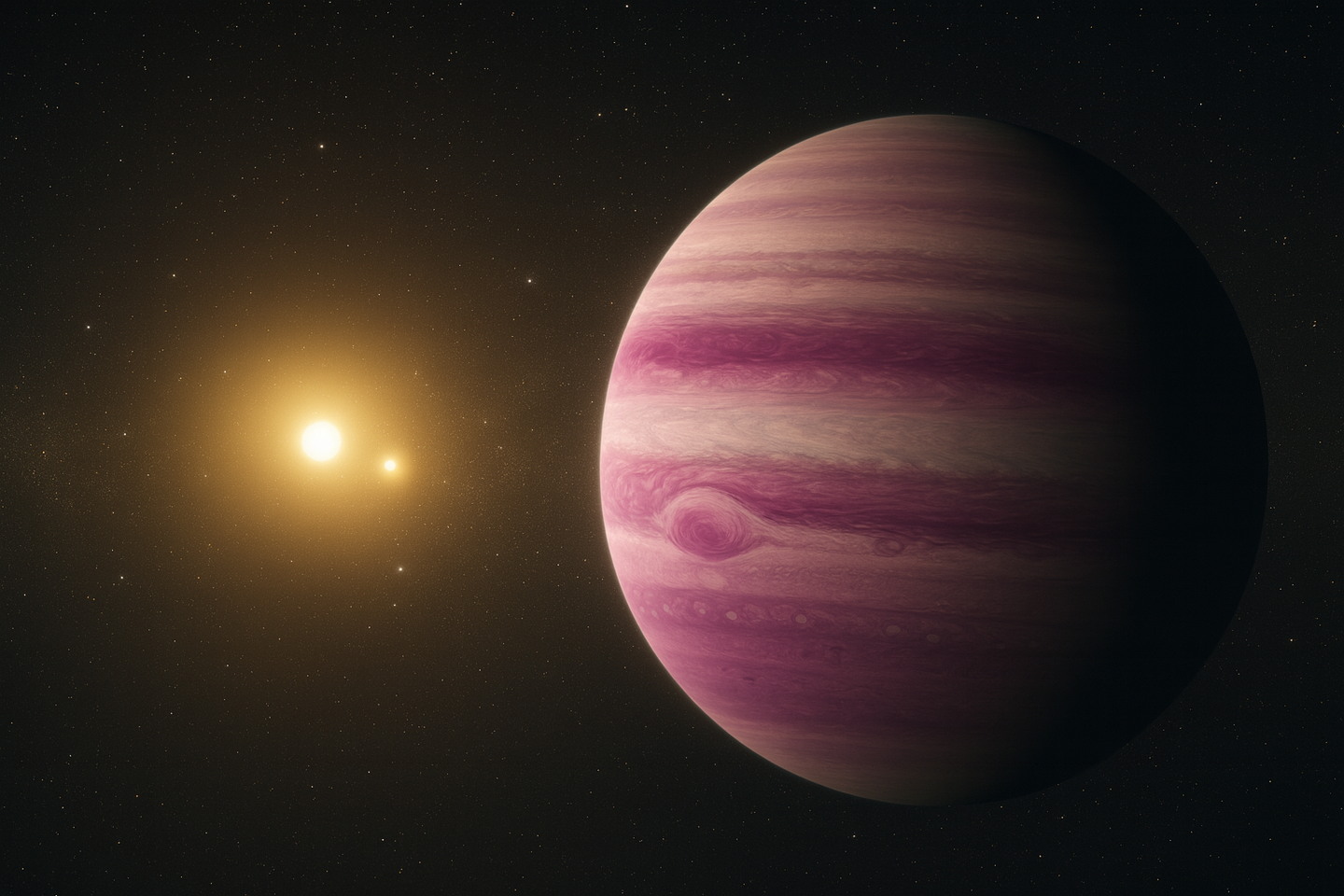

A massive young planet orbiting two tightly bound stars has been directly imaged for the first time at solar system–like distances. (CREDIT: AI-generated image / The Brighter Side of News)

Astronomers have confirmed a giant planet orbiting a tightly bound pair of young stars, marking a first in direct exoplanet imaging. The planet, known as HD 143811 AB b, is the closest-in world ever directly observed circling a binary star system at distances comparable to the outer solar system.

The planet carries an estimated mass between five and six times that of Jupiter and orbits its two suns at roughly 60 astronomical units. That distance is about twice Pluto’s separation from the Sun. While the orbit is wide, it is far closer than most previously imaged planets around binary stars.

The host stars form a close spectroscopic binary, meaning the pair is too tight to resolve directly but reveals itself through shifting spectral lines. Together, they reside in the Scorpius-Centaurus star-forming region, about 446 light-years from Earth. The system’s young age, estimated at 13 plus or minus four million years, allows the planet to glow in infrared light from retained formation heat.

What sets this discovery apart is not just the planet’s size or youth. It is the first time astronomers have directly imaged a planet orbiting two stars at solar system–like scales. That placement makes the system a valuable testbed for understanding how planets form and survive in gravitationally complex environments.

Why direct imaging is so difficult

Capturing an image of a distant planet ranks among astronomy’s hardest tasks. Stars can outshine nearby planets by millions or even billions of times. To overcome this, astronomers rely on adaptive optics, coronagraphs, and advanced image-processing techniques to isolate faint planetary light.

Since the mid-2000s, direct imaging has uncovered a small number of massive planets orbiting young stars. Many emerged from targeted searches where earlier data hinted at a companion. Others came from wide surveys of nearby youthful stars, where newly formed planets shine brightest in infrared wavelengths.

Direct imaging offers rare advantages. By watching a planet over time, astronomers can trace its orbit and test whether it remains stable. Spectral data also reveal atmospheric temperature, composition, and rotation. These measurements are difficult or impossible to obtain with other detection methods.

Binary stars add another layer of difficulty. Many surveys avoid them altogether because two stellar light sources complicate observations and analysis. As a result, very few directly imaged planets are known around binaries, and most orbit at extreme distances. HD 143811 AB b fills a long-standing gap.

“Of the 6,000 exoplanets that we know of, only a very small fraction of them orbit binaries,” said Northwestern University’s Jason Wang, one of the senior authors of the study. “Of those, we only have a direct image of a handful of them, meaning we can have an image of the binary and the planet itself. Imaging both the planet and the binary is interesting because it’s the only type of planetary system where we can trace both the orbit of the binary star and the planet in the sky at the same time. We’re excited to keep watching it in the future as they move, so we can see how the three bodies move across the sky.”

Is It Rare for Binary Stars to Have Exoplanets

"We don't actually know how rare planets around binary stars are because they usually aren't included in planet-searching surveys. This is because of the technique we use to block out the light from the star so we can see the planet orbiting it. There is a worry that both stars might not fit and not be blocked out correctly," Nathalie Jones told The Brighter Side of News. "However, in this case the two stars are orbiting each other very close together, so this isn't a problem in capturing the image of HD 143811 AB b. Now that we know it's possible to have planets around binary stars, we can go looking for them," she continued.

"I'd just add that adding a second star in the system is generally disruptive due to its strong gravitational pull (e.g., it can eject planets or suck up the dust and gas that would otherwise be available to form planets). Because of that, it's hard to form planets too close to the stellar binary (we know that from previous studies). For planets this far out, it's not very clear how the binary affects planet formation like Nathalie says, so we need to find and study more of them." Jason Wang expanded on Nathalie's thoughts.

A fast-dancing pair of young stars

The host stars orbit each other every 18.59 days and have nearly equal masses. Their rapid motion places strong gravitational forces on any surrounding material. That environment makes planet formation more challenging than around a single star.

To characterize the system, researchers combined high-resolution spectroscopy with stellar evolution models. They built a synthetic energy distribution for the unresolved stellar pair, drawing on Gaia and infrared survey data. A statistical approach allowed them to constrain stellar masses, metallicity, age, and distance.

This stellar model later served as a reference for interpreting the planet’s faint spectrum. Understanding the stars proved essential for determining whether the detected object was truly a planet or simply a background star.

Finding a planet hiding in old data

The planet first appeared in observations from the Gemini Planet Imager, a high-contrast instrument once mounted on the Gemini South telescope in Chile. The instrument combines adaptive optics, a coronagraph, and an infrared spectrograph to detect faint companions near bright stars.

The system was observed twice, once in 2016 and again in 2019. In both cases, astronomers recorded dozens of one-minute exposures in the H band. Automated pipelines transformed raw data into calibrated spectral cubes, corrected distortions, and removed instrumental noise.

Advanced algorithms then subtracted the stellar light. A faint point source emerged at a consistent location, detected with moderate confidence in both epochs. The signal remained weak enough that it escaped earlier analysis.

To refine the planet’s position and brightness, the team used forward-modeling techniques that simulated how the planet’s signal passed through the data-processing steps. Bayesian fitting accounted for correlated noise and instrumental uncertainties.

Confirming motion and binding

A third observation came in 2022 from the NIRC2 camera at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii. This time, astronomers observed the system in longer infrared wavelengths, where the planet emits more strongly.

Using nearly 90 minutes of on-target exposure, the team again detected the planet. Across all three epochs, the object remained at a projected separation of about 60 astronomical units. Its position angle shifted in a way consistent with orbital motion.

To rule out a background star, researchers compared the planet’s movement against expected motion for an unrelated object, using the system’s known parallax and proper motion. The observed path deviated strongly from the background track and instead followed a bound orbit.

Orbit modeling suggests a moderately inclined path with low to moderate eccentricity and an orbital period of roughly 300 years. While the stellar binary’s own motion complicates precise mass estimates, the results firmly establish the planet as gravitationally bound.

A young giant with a warm glow

Spectral analysis provided another key confirmation. The team compared the planet’s infrared spectrum with models of stars and exoplanet atmospheres. When combined with longer-wavelength photometry, the data strongly favored a planetary origin.

Atmospheric models indicate an effective temperature near 1,000 Kelvin. While gravity and composition remain uncertain, the planet’s luminosity and radius align with expectations for a young gas giant.

Using evolutionary models appropriate for the system’s age, astronomers estimate a mass of about 5.6 Jupiter masses and a radius slightly larger than Jupiter’s. These values place HD 143811 AB b among a small group of directly imaged young giants with similar properties.

On a color–magnitude diagram, the planet falls near late L-type or early T-type objects. Its colors resemble those of other dusty, complex atmospheres, hinting at thick clouds or unusual chemistry.

A benchmark for planets around two suns

HD 143811 AB b now stands as the closest-in directly imaged planet known around a binary star. It also represents the first such planet found at distances comparable to the outer solar system.

The discovery carries broader importance. It challenges and informs models of planet formation, particularly core accretion, under the influence of two stars. It also supports survey results showing that wide-orbit giant planets remain uncommon.

As instruments improve and upgraded imagers come online, astronomers expect to uncover more planets in similar systems. Each new find will help clarify how common such worlds are and how they evolve.

This planet, glowing faintly in archival starlight, shows that major discoveries can still hide in existing data, waiting for sharper tools and fresh eyes.

------ Story updated on Dec. 15, 2025 ------

The section titled "Is It Rare for Binary Stars to Have Exoplanets" was added to the story to expand reporting on the rarity of binary star exoplanets as provided by the researchers directly to The Brighter Side of News post initial artcile publication.

Research findings are available online in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Related Stories

- How NASA turned exoplanets into tourist destinations

- Astronomers identify real-life Tatooine using new method

- Exoplanet TRAPPIST-1e may hold Earth-like atmosphere, JWST finds

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.