Breakthrough cancer treatment reverts cancer cells to their normal state

New research is transforming aggressive triple-negative breast cancer cells into normal, non-proliferating cells.

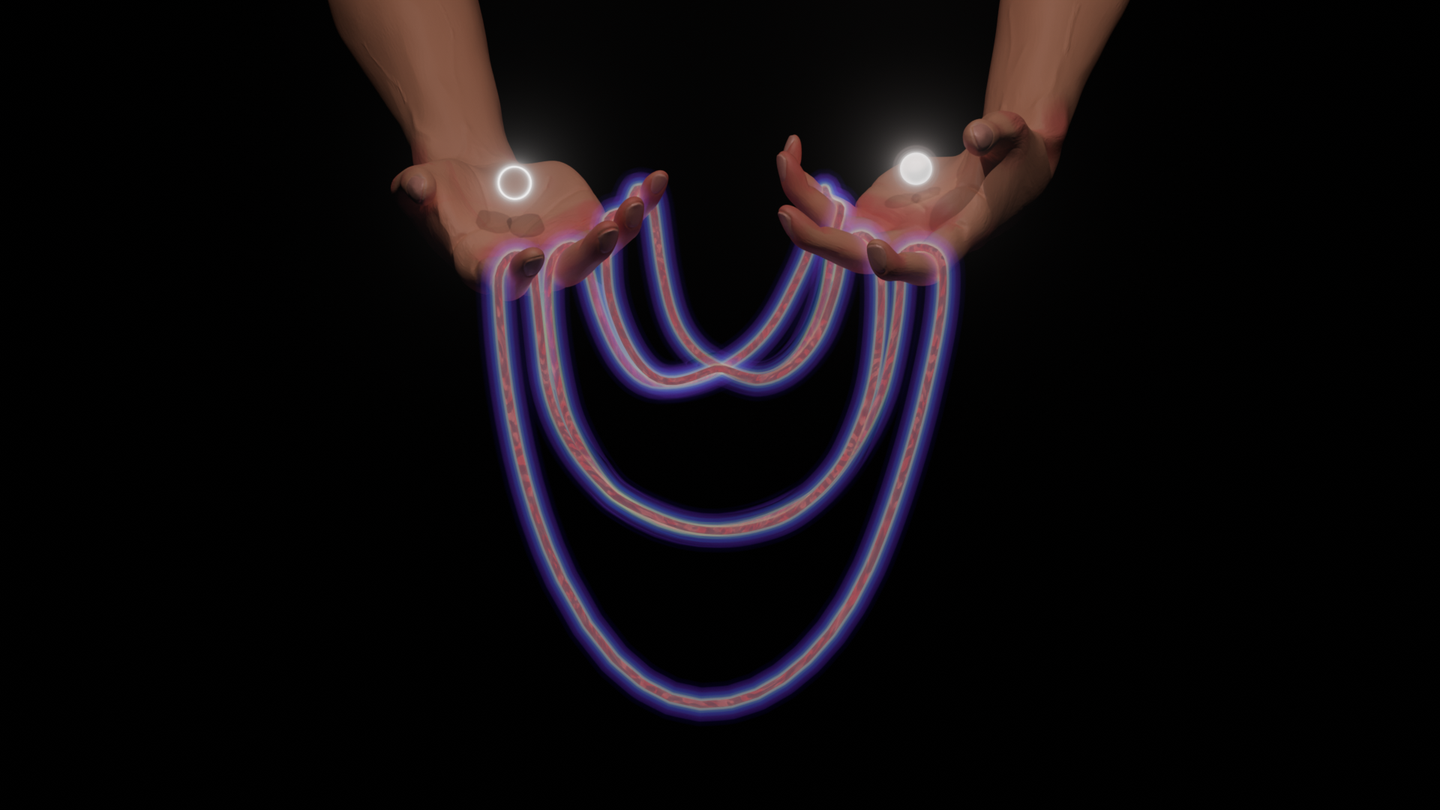

Scientists have found a groundbreaking way to combat triple-negative breast cancer by making its aggressive cells act more like normal ones. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Cancer cells possess a remarkable quality called plasticity. This means they can change their form. This ability helps them survive and spread.

Cancer cells act like young cells. They can adapt to different body parts. They can also resist drug treatments. But what if this very quality could be used against them? Scientists are exploring this idea. They want to make cancer cells more like normal cells. This could stop their dangerous growth.

Unlocking a New Path for Breast Cancer Treatment

Breast cancer is a major health concern for women. A very aggressive type is triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). It is hard to treat. This cancer lacks important markers. These include the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα). Its high plasticity makes it very dangerous. It has a poor outlook. But new research offers hope. Scientists found a way to target this plasticity. They aim to make these aggressive cells less harmful.

Normal breast cells have ERα. These cells are mature. They do not grow uncontrollably. In contrast, many breast cancers have ERα. But these cells grow too much. They can be treated with anti-estrogen drugs. These treatments work well. However, TNBC does not respond to these drugs. It often affects younger women. It has limited treatment choices.

Researchers at the University of Basel and the University Hospital Basel wanted to change this. They wondered if TNBC cells could be made to express ERα. This could make them treatable. Professor Mohamed Bentires-Alj leads this research group. They published their findings in the journal Oncogene.

A Surprising Discovery

The team had a clever idea. They wanted to turn TNBC into a more treatable type. Dr. Milica Vulin, the lead author, explained their goal. “Our initial idea was to induce estrogen receptor expression in order to convert triple-negative breast cancer into estrogen-receptor positive breast cancer because of more effective treatment options available for this subtype,” she stated.

Related Stories

They screened many compounds. Over 9,500 substances were tested. They looked for those that could increase ERα. They found three strong candidates. These were inhibitors of a protein. This protein is called polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1). PLK1 is vital for cell division.

What happened next was a big surprise. Inhibiting PLK1 did more than expected. It increased ERα. But it also pushed the cancer cells. It made them differentiate. This means they became more like normal cells. They stopped growing. They even started to die. This was a major breakthrough. It suggested a new way to fight TNBC.

How PLK1 Inhibition Works

PLK1 inhibition sets off a chain of events. It causes DNA damage. It stops cell division. This leads to cell death. Even cells that survive change. They lose their ability to form tumors. This was seen in lab tests. It was also seen in patient-derived models. Targeting PLK1 slowed tumor growth. It made cancer cells less dangerous.

The changes upon PLK1 inhibition are significant. Genes that turn on also appear in normal breast tissue. Their expression links to better survival. This provides strong evidence. PLK1 inhibition could be a new therapy. It’s called differentiation therapy. This type of therapy has worked for blood cancers. Now, it shows promise for solid tumors.

Future Hopes for Treatment

Understanding cancer is key. Knowing how cancer cells differ from normal ones helps. Professor Bentires-Alj emphasized this. “Understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms that define cancer and how these mechanisms differ from normal cells is crucial for developing new innovative therapies,” he said. This research opens a new door. It offers hope for TNBC patients.

The compounds used are already in trials. They are being tested for other cancers. These include blood, lung, and pancreatic cancers. This means they could be tested soon for breast cancer. This speeds up the process. It brings new treatments closer to patients.

There’s another exciting possibility. Combining differentiation therapy with immunotherapy. Immunotherapy uses the body's immune system. It helps fight cancer. Normal-like cells might be easier targets. Immune cells could clear them away. Cancer cells often evade the immune system. Making them more normal could change this. The researchers are hopeful. They are pursuing these strategies. They believe that with time and resources, more progress will be made.

Types of Breast Cancer

Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (IDC)

- This is the most common type of breast cancer, accounting for about 70–80% of all cases. IDC begins in the milk ducts and then invades nearby breast tissue. It can spread to lymph nodes and other parts of the body if untreated.

- Symptoms often include a hard lump in the breast, nipple discharge, changes in breast shape, or skin dimpling. IDC affects both men and women but is far more common in women. Globally, IDC contributes to the majority of the 2.3 million new breast cancer cases reported each year.

- Standard treatments include surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy), radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy (for hormone receptor-positive tumors), and targeted drugs like trastuzumab for HER2-positive forms.

Invasive Lobular Carcinoma (ILC)

- ILC makes up about 10–15% of invasive breast cancers. It starts in the lobules—the glands that produce breast milk—and gradually spreads to surrounding tissues. Unlike IDC, ILC can be harder to detect on mammograms because it grows in a linear or diffuse pattern rather than forming a distinct lump.

- Symptoms may include breast thickening, swelling, or a subtle change in texture rather than a noticeable lump. ILC is most common in postmenopausal women and has a slightly higher chance of appearing in both breasts.

- Treatment often mirrors that for IDC, involving surgery, radiation, hormonal therapy (especially since ILC is frequently estrogen-receptor positive), and occasionally chemotherapy depending on tumor grade and spread.

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS)

- DCIS is a non-invasive or pre-invasive breast cancer, meaning the cancer cells are confined to the milk ducts and haven’t spread to surrounding tissue. It accounts for about 20% of new breast cancer diagnoses, often discovered during routine mammography.

- DCIS typically doesn’t cause a palpable lump or symptoms, though some individuals may notice nipple discharge or a small localized area of pain. While not life-threatening, DCIS can develop into invasive cancer if left untreated.

- Treatment commonly includes lumpectomy followed by radiation, or mastectomy in more extensive cases. Hormone therapy may also be used if the DCIS is hormone receptor-positive.

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)

- Triple-negative breast cancer represents about 10–15% of breast cancer cases and is more common in younger women, Black women, and those with BRCA1 mutations. It is called “triple-negative” because it lacks estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and excess HER2 protein, which makes it unresponsive to most hormone or HER2-targeted therapies.

- TNBC is often aggressive, with a higher likelihood of spreading and recurring. Symptoms are similar to other invasive cancers—lumps, breast pain, or changes in appearance—but progression tends to be faster.

- Treatment primarily involves surgery and chemotherapy, and recent advances include immunotherapy and PARP inhibitors, particularly for BRCA mutation-positive cases.

HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

- HER2-positive cancers make up about 15–20% of cases and are characterized by overexpression of the HER2 protein, which promotes cancer cell growth. These cancers tend to grow and spread more rapidly than HER2-negative types.

- Symptoms may include breast lumps, swelling, redness, or nipple changes. HER2-positive breast cancer affects people of all ages but is often diagnosed in younger women.

- Treatment typically includes HER2-targeted therapies such as trastuzumab (Herceptin) and pertuzumab, along with chemotherapy and sometimes hormone therapy if the tumor also expresses hormone receptors. Targeted therapies have significantly improved survival rates in recent years.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.