Can a 3-D printer generate human organs … in outer space?

NASA has a problem. It wants to send humans on long-distance space missions but the human body does not thrive under the rigors of space

[June 10, 2021: Zachery Eanes]

NASA has a problem.

It wants to send humans on long-distance space missions — to Mars or beyond — but the human body does not thrive under the rigors of space.

Whether it is the loss of gravity or the abundance of radiation, our bodies age quickly beyond the confines of Earth. Humans who have spent more than several weeks in orbit have lost density in their bones and skeletal muscle mass, developed cardiovascular issues and suffered immune dysfunction.

But a group of scientists from North Carolina could be on the path to helping NASA find solutions to that problem.

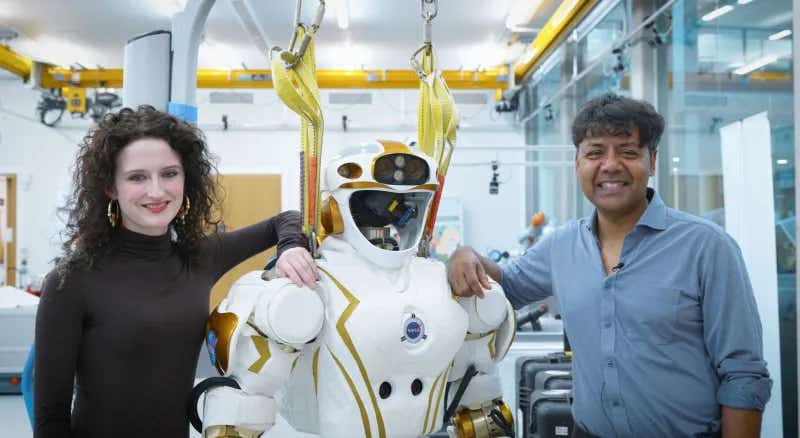

On Wednesday, NASA said researchers from the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine were the winners of a competition to build lab-grown human tissue models it could use for experiments in space.

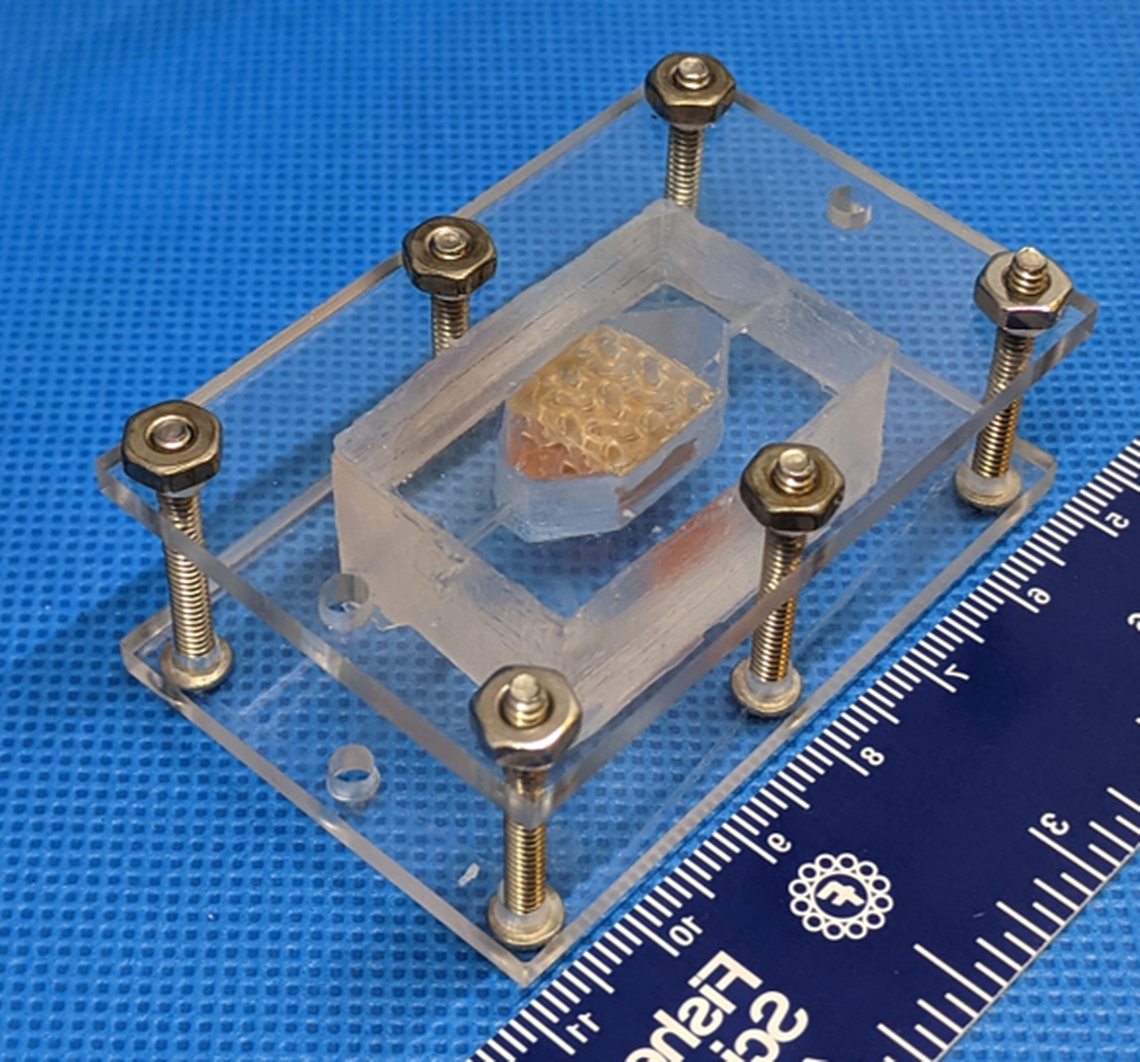

The Wake Forest scientists, which included two different teams based in Winston-Salem, won the competition by 3D printing lab-grown human liver cells and placing them inside a specially-designed chamber that mimicked the human circulation system. The chamber was able to keep the cells alive for an entire month.

The Wake Forest team received $300,000 in prize money from NASA for winning the competition.

More importantly, its tissue model will now go on board the International Space Station (ISS), where it could pave the way for important advances in regenerative medicine, a branch of science that seeks to find ways to regrow or repair damaged human cells and organs.

“We could be able to test the impacts of microgravity on tissues right here on the International Space Station,” astronaut Kate Rubins said in a video conference call from the space station on Wednesday. “This could pave the way for medical breakthroughs.”

So far, the models only sustain one centimeter chunks of lab-grown liver cells. But Jim Reuter, NASA associate administrator for space technology, said the experiments could be a building block to one day making artificial organ transplants a reality. Instead of waiting on donation lists for an unknown period of time, one day we might be able to print entire organs from an individual’s own cells. Perhaps it could also extend the amount of time a human can withstand space travel.

“I cannot overstate what an impressive accomplishment this is. When NASA started this challenge in 2016, we weren’t sure there would be a winner,” Reuter said in a statement. “It will be exceptional to hear about the first artificial organ transplant one day and think this novel NASA challenge might have played a small role in making it happen.”

The NASA competition to create the lab-grown human cell models started about six years ago in partnership with the Methuselah Foundation, a nonprofit focused on extending human life.

Initially, the Methuselah Foundation wanted to focus on the creation of a whole liver that could be viable for three months, the foundation’s co-founder Dave Gobel said at the press conference.

“But we were way too early, and the technology didn’t support that goal,” he said. “The real problem was that you could not scale the tissues up above 20 cells thick. The tissues would begin to die because of a lack of blood flow.”

The Wake Forest team solved that issue by creating a gel-like mold that allowed for the flow of oxygen and nutrients.

“It ended up being a modified gelatin, sort of similar to what you might make Jello out of at home in your kitchen,” said Kelsey Willson, a member of the Wake Forest team. “And then (we built) a circulation system that we could get fluid flow through to really allow these samples to be perfused in a way similar to what you see in the human body.”

Still, the Wake Forest models represent incremental progress. Eventually, scientists will likely be able to create entire lab-grown organs, Willson said, but not at the moment.

“I won’t say that we’re going to create a liver in lab next month,” she said. “That might be a little far out for us, there are several things that need to be optimized before then, including, How do we get enough cells to be able to print something that large? Growing cells is a hurdle that needs to be overcome.”

Willson said her team hopes to create something larger than one centimeter next.

Gobel, of the Methuselah Foundation, sounded a more optimistic note.

He believes that in just a few years scientists might be able to create 3D-printed tissue that could help repair a sick organ. And soon after that, he believes his organization’s original goal of creating whole organs might be possible.

“In the next 10 to 15 years,” he said, “I would say that we would be able to get whole livers and whole kidneys.”

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Tags: #New_Innovation, #Medical_Innovation, #Space, #NASA, #The_Brighter_Side_of_News