Common dietary supplement could help flush PFAS from your body

Researchers find gel-forming fiber supplements may help the body flush PFAS forever chemicals linked to serious health risks.

Scientists discover that gel-forming fiber supplements, taken with meals, could help the body excrete PFAS. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0)

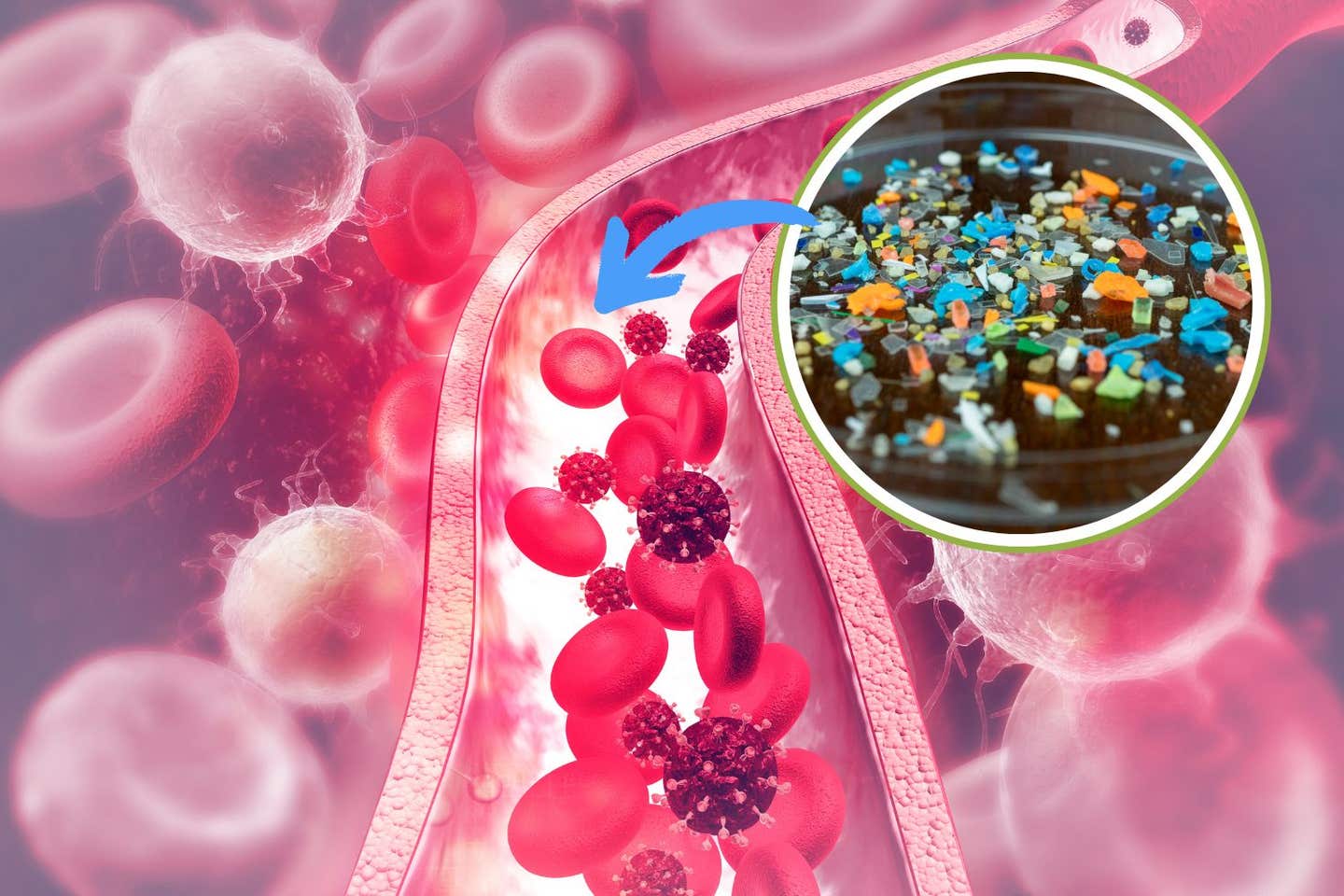

They make raincoats shed water, pans resist sticking, and carpets repel stains. They can even put out fuel fires. Yet these same compounds—PFAS, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances—linger in your body and the environment for decades. Nature has no easy way to destroy them, which is why scientists call them “forever chemicals.”

In the United States, it’s almost impossible to avoid exposure. “Every person in the United States, essentially, is walking around with PFAS in their body,” says Jennifer Schlezinger, a Boston University School of Public Health professor of environmental health. These chemicals have been linked to weaker vaccine responses, high cholesterol, liver toxicity, hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, and low birth weights in infants.

Schlezinger’s recent research offers hope. She found that taking a specific type of fiber supplement with meals might help your body flush out some PFAS. Her study, published in Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, suggests that gel-forming fibers may trap the chemicals in the digestive system and carry them away during digestion.

A Chemical Threat That Travels Through Water

PFAS are a family of more than 12,000 man-made chemicals with strong carbon-fluorine bonds, making them resistant to heat, oil, and water. Because they dissolve easily in water, they spread quickly through groundwater, rivers, and oceans. Contaminated drinking water is a major source of exposure, along with certain foods such as seafood, eggs, and brown rice.

“They’re water-soluble, and that’s part of the problem,” Schlezinger explains. “People are largely being exposed through contaminated drinking water, through contaminated food, and then, in part, from products within one’s home.”

Once PFAS enter your body, they bind to proteins in the blood and liver. Unlike many other toxins, they are not easily broken down or excreted. Over time, their concentration rises. “The longer something stays in the body, the more likely it is to cause toxicity,” Schlezinger says.

Related Stories

- New sensor offers cheap and fast way to detect harmful “forever chemicals” in drinking water

- New innovation destroys 90% of toxic 'forever chemicals' in water

From Lowering Cholesterol to Targeting PFAS

Schlezinger’s discovery began as a personal health experiment. She wanted to lower her cholesterol without taking medication, so she started looking into dietary solutions. Her research led her to gel-forming fibers, which form a thick substance when mixed with water. One example is cholestyramine, a fiber that binds to bile acids during digestion. The body replaces those lost bile acids by pulling cholesterol from the blood, lowering cholesterol levels.

She realized PFAS share some chemical features with bile acids. Both are surfactants, meaning they have a neutral end and a charged end, allowing them to stick to fibers. If a fiber can bind bile acids, maybe it can bind PFAS, too.

That idea became the foundation for her studies. Working with Dhimiter Bello at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, she tested samples from a clinical trial of oat beta-glucan, another gel-forming fiber. The results showed a statistically significant drop in PFAS levels in participants who took the fiber supplement.

Support From the Department of Defense

Their early findings drew interest from the Department of Defense’s Toxic Exposures Research Program. This program funds work aimed at reducing the health impact of toxic exposures, including those faced by military personnel. PFAS contamination is a known issue near some military bases due to firefighting foams.

Schlezinger’s team includes Chelsea Simone, an Army veteran and nurse practitioner who advises them on veterans’ concerns. With funding in place, Schlezinger expanded her work to test seven diets, each using different gel-forming fibers, to see which is most effective.

The initial human studies had limits. Participants took supplements for only four weeks, and researchers could not control for ongoing PFAS exposure from food and water. The trial included only men with high PFAS levels, since menstruation can naturally lower PFAS in the body. “We want to figure out if we’re right: Is the hypothesis correct when we are testing it in a very controlled scenario?” Schlezinger says.

She also suspects that mixing different gel-forming fibers could be more effective than using just one. “We want to maximize how well this approach works,” she adds.

The Current Regulatory Landscape

PFAS regulation in the U.S. is in flux. In March, the Trump administration announced rollbacks on limits for PFAS in drinking water. Schlezinger believes that’s a mistake, though she notes the changes have not yet taken effect. “It’s not good news by any way, shape, or form,” she says. “But PFAS are not threatening people any more than they are right now.”

While long-term policy decisions remain unsettled, her research focuses on practical, immediate steps people can take. She is careful not to suggest that eating a high-fiber diet alone will solve the problem. Instead, she recommends considering dietary supplements as a more accessible option. “It’s feasible,” she says. “I bought every single supplement, every single fiber that I’m testing, on Amazon.”

Fiber Supplements and Feasibility

One of the most well-known gel-forming fibers is psyllium, the active ingredient in Metamucil. Another is oat beta-glucan, which Schlezinger has been taking daily for over two years. She mixes a scoop into pomegranate juice and drinks it with meals. “It’s done amazing things for my cholesterol,” she says. “I don’t have to take any drugs. I’m back to normal.” Her husband, also a participant in the experiment, calls the taste “gross,” but takes it anyway.

Still, she warns against seeing fiber supplements as a quick fix. “I don’t want to imply that you’re going to take a fiber supplement for a few months and the PFAS are going to be gone,” she says. The process is gradual, and PFAS exposure continues for most people.

Before increasing fiber intake significantly, Schlezinger advises consulting a doctor. Fiber can affect digestion, medication absorption, and other aspects of health. But she sees promise in this approach, especially compared with older methods of reducing PFAS levels, like bloodletting.

The Bigger Picture

PFAS have been in use since the 1940s and are found in thousands of products, from fast-food wrappers to firefighting foam. Their durability means they can persist in soil and water for centuries. Cleaning them up at the environmental level is difficult and expensive. While research into large-scale solutions continues, finding ways to lower their levels inside the human body could make a big difference.

For Schlezinger, the work is both personal and professional. What began as an experiment to lower her cholesterol has turned into a potential public health tool. If gel-forming fibers can reduce PFAS levels safely and effectively, they could help people around the world protect themselves from an invisible but persistent chemical threat.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.