Could a child have painted that Jackson Pollock?

Poured paintings carry unique patterns shaped by age, movement, and balance, offering fresh insight into art and perception.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

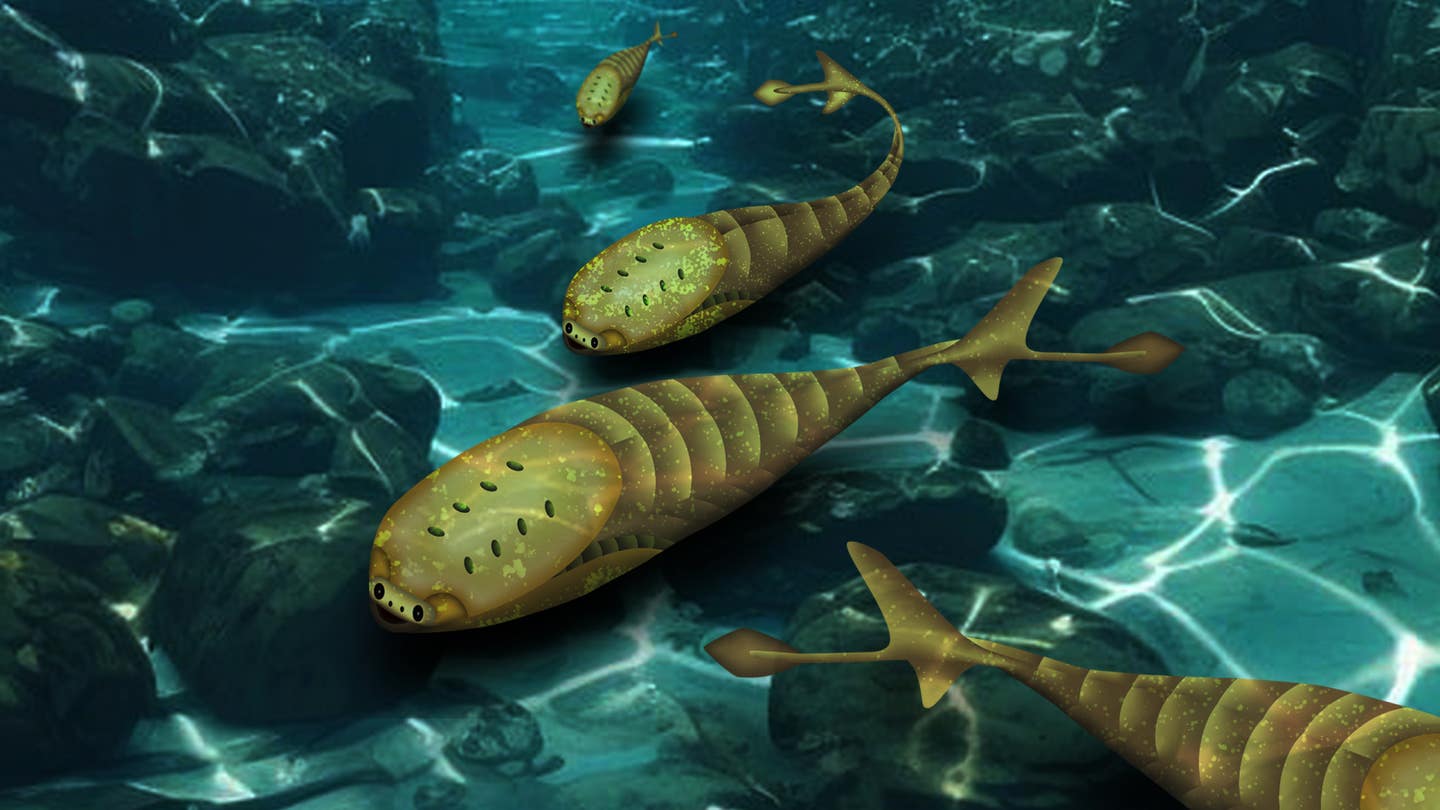

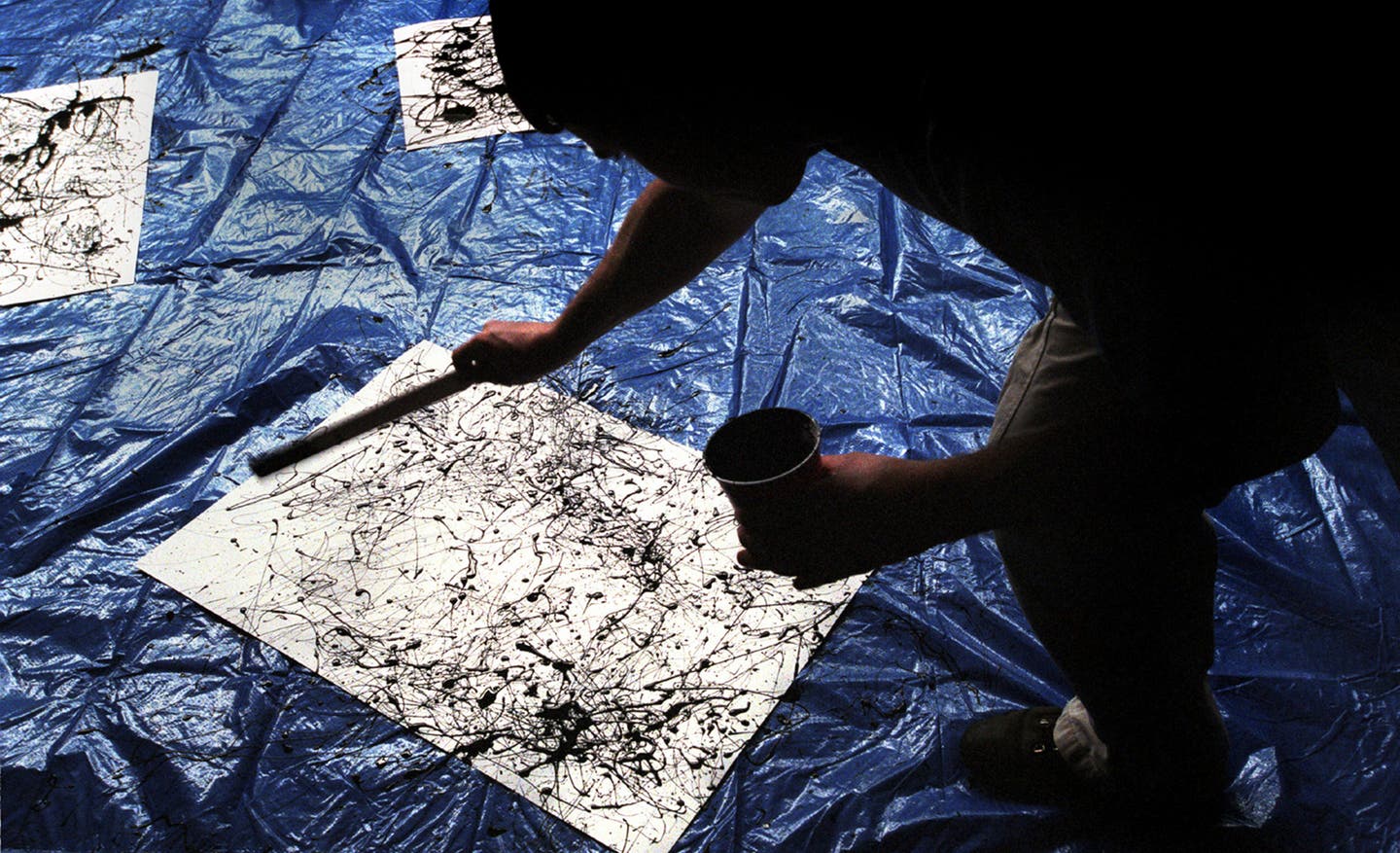

During the ‘dripfest’ experiment adults and children were asked to recreate a painting in Pollock’s style. (CREDIT: Richard Taylor)

At first glance, the act of pouring paint across a canvas looks wild. Paint drops through the air, twists with each motion of the wrist, and splashes into tangled paths that seem to follow no plan. Yet you may sense something deeper in those swirling lines. A new study suggests that these patterns reveal much more about the person holding the stick than anyone realized.

Scientists have long asked whether artists who drip and sling paint have real control over the final image. Jackson Pollock is the most famous example. He worked above horizontal canvases, letting liquid paint scatter across the surface. Many critics saw his pieces as disorder without structure. Others believed the technique carried a kind of personal signature that reflected the artist’s movements. This new research brings that debate into the lab.

A Closer Look at Poured Art

The project began with a simple question. Can a poured painting show whether it was made by an adult or a young child? To test that idea, researchers from the United States asked 18 children between four and six years old and 34 adults between 18 and 25 to create Pollock-style pieces. Everyone used the same tools, the same diluted vinyl paint, and the same size paper on the floor. Each person saw the same reference images and followed the same instruction to make something in the spirit of Pollock.

When the paintings dried, they were scanned at high resolution and turned into black and white images. This step helped the team focus only on the patterns made by the paint. Two famous poured works were added for comparison: Pollock’s “Number 14, 1948” and Max Ernst’s “Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly.”

To measure the structure of each piece, the team used two tools. The first was fractal analysis. Fractals appear in nature and repeat at different scales. You see them in trees, rivers, and clouds. In poured art, fractal measures show how much detail fills a surface as you zoom in and out. Higher values mean the pattern has more branching and complexity.

The second tool was lacunarity. This looks at how evenly or unevenly empty spaces appear in a pattern. High lacunarity means the gaps are irregular and clumpy. Low values mean the gaps are smoother and more uniform.

What Age Reveals on the Canvas

The results were clear. Adults created paintings with much higher fractal dimensions. Their lines were richer, more varied, and denser. The paint often shifted direction, changed thickness, and filled the space with many small features.

Children’s paintings looked different. Their lines were simpler, smoother, and far less varied. Their pieces showed more clumping and more space between paint clusters. Their lacunarity values were much higher. On average, adults reached a fractal dimension of D₀ = 1.907. Children reached 1.688. The contrast held across other measures as well.

According to the researchers, these results may reflect motor control and balance. Young children move differently because their bodies are still developing. Earlier studies show they make simpler motions and fewer fine-scale corrections. Adults make more precise shifts in weight and direction. When paint falls through the air, even small changes in body movement shape how lines twist, break, or drip.

Prof. Richard Taylor of the University of Oregon, senior author of the study, explained the discovery. “Our study shows that the artistic patterns generated by children are distinguishable from those created by adults when using the pouring technique made famous by Jackson Pollock,” he said. “Remarkably, our findings suggest that children’s paintings bear a closer resemblance to Pollock paintings than those created by adults.”

How Viewers Respond to Poured Paint

The team also tested how people perceive poured paintings. Ninety-one adults viewed nineteen pieces made by the adult volunteers. They rated each one on complexity, interest, and pleasantness.

The three ratings were strongly linked. When a painting was seen as more complex, it was also rated as more interesting and more pleasant. But complexity on its own did not match fractal values in this dataset. Earlier studies found that link only across a wider range of fractal dimensions.

The most surprising result came from lacunarity. Paintings with more clumpy spacing were rated as more pleasant and interesting. Since the children’s work showed higher lacunarity, this trend hints that their pieces may appeal to viewers in ways the adults’ pieces do not.

Taylor believes this response may stem from the natural world. “Our previous research indicates that our visual systems have become ‘fluent’ in the visual languages of fractals through millions of years of exposure to them in natural scenery,” he said. “This ability to process their visual information triggers an aesthetic response. Intriguingly, this means that the children’s poured paintings are more attractive than the adult ones.”

How Famous Works Fit Into the Picture

Pollock’s painting fell within the adult ranges for all measurements, although it rested close to the children’s boundary. The Ernst painting landed squarely in the children’s range. That may reflect his use of a swinging pendulum to drip paint, a tool that reduced the influence of natural body movement.

Taylor noted that many artists face physical limits that shape their style. “Along with Claude Monet’s cataracts, Vincent van Gogh’s psychological challenges, and Willem de Kooning’s Alzheimer’s condition, art historical discussions of Pollock’s limited biomechanical balance serve as a reminder that conditions that present challenges in aspects of our daily lives can lead to magnificent achievements in art,” he said.

Practical Implications of the Research

This work suggests that poured paintings hold measurable traces of human movement. Those traces may someday help experts study artistic style, authenticity, and motor behavior.

The findings also support earlier research showing that certain fractal patterns reduce stress, a topic that grew more relevant during the Covid-19 pandemic. By linking body mechanics to the visual appeal of fractals, the study may inspire new uses in art therapy, wellness, and design.

Future studies using motion sensors could show exactly how balance, posture, and gesture produce the structures we see in poured paint.

Research findings are available online in the journal Frontiers in Physics.

Related Stories

- Art as medicine: Viewing paintings helps mental health, study finds

- Advanced AI cracks 500 year-old art mystery

- AI-Powered FRIDA robot collaborates with humans to create art

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Science & Technology Journalist | Innovation Storyteller

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. With a passion for uncovering groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, she brings to light the scientific advancements shaping a better future. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs and artificial intelligence to green technology and space exploration. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.