Popping the top off the mystery of how many bubbles are in a glass of beer

Let’s set the scene. It’s a little past midnight and you are hunched over a pint at your favorite watering hole, 4 pints to the wind…

[Apr. 21, 2021: American Chemical Society]

Let's set the scene. It's a little past midnight and you are hunched over a pint at your favorite watering hole, 4 pints to the wind and wondering what will become of the rest of the night. Suddenly, through increasingly slitted eyes you notice a single bubble slowly fighting its way to the top of your glass. How did it get there and how many friends does he have? Maybe not surprisingly, scientists may now have your answer.

After pouring beer into a glass, streams of little bubbles appear and start to rise, forming a foamy head. As the bubbles burst, the released carbon dioxide gas imparts the beverage's desirable tang. But just how many bubbles are in that drink? By examining various factors, researchers reporting in ACS Omega estimate between 200,000 and nearly 2 million of these tiny spheres can form in a gently poured lager.

Worldwide, beer is one of the most popular alcoholic beverages. Lightly flavored lagers, which are especially well-liked, are produced through a cool fermentation process, converting the sugars in malted grains to alcohol and carbon dioxide. During commercial packaging, more carbonation can be added to get a desired level of fizziness. That's why bottles and cans of beer hiss when opened and release micrometer-wide bubbles when poured into a mug. These bubbles are important sensory elements of beer tasting, similar to sparkling wines, because they transport flavor and scent compounds. The carbonation also can tickle the drinker's nose. Gérard Liger-Belair had previously determined that about 1 million bubbles form in a flute of champagne, but scientists don't know the number created and released by beer before it's flat. So, Liger-Belair and Clara Cilindre wanted to find out.

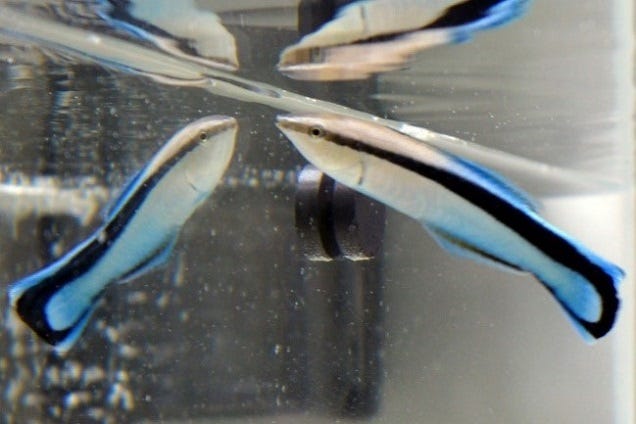

The researchers first measured the amount of carbon dioxide dissolved in a commercial lager just after pouring it into a tilted glass, such as a server would do to reduce its surface foam. Next, using this value and a standard tasting temperature of 42 F, they calculated that dissolved gas would spontaneously aggregate to form streams of bubbles wherever crevices and cavities in the glass were more than 1.4 μm-wide. Then, high-speed photographs showed that the bubbles grew in volume as they floated to the surface, capturing and transporting additional dissolved gas to the air above the drink.

As the remaining gas concentration decreased, the bubbling would eventually cease. The researchers estimated there could be between 200,000 and 2 million bubbles released before a half-pint of lager would go flat. Surprisingly, defects in a glass will influence beer and champagne differently, with more bubbles forming in beer compared with champagne when larger imperfections are present, the researchers say.

Like these kind of stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter

The authors acknowledge funding from the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS).

The paper is freely available as an ACS AuthorChoice article here.

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS' mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a specialist in scientific information solutions (including SciFinder® and STN®), its CAS division powers global research, discovery and innovation. ACS' main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

Tags: #New_Discovery, #Beer, #The_Brighter_Side_of_News