Dark Energy Survey delivers its most precise cosmic map yet

The Dark Energy Survey’s final results narrow the mystery of dark energy, offering sharper questions and new tools for future cosmic exploration.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

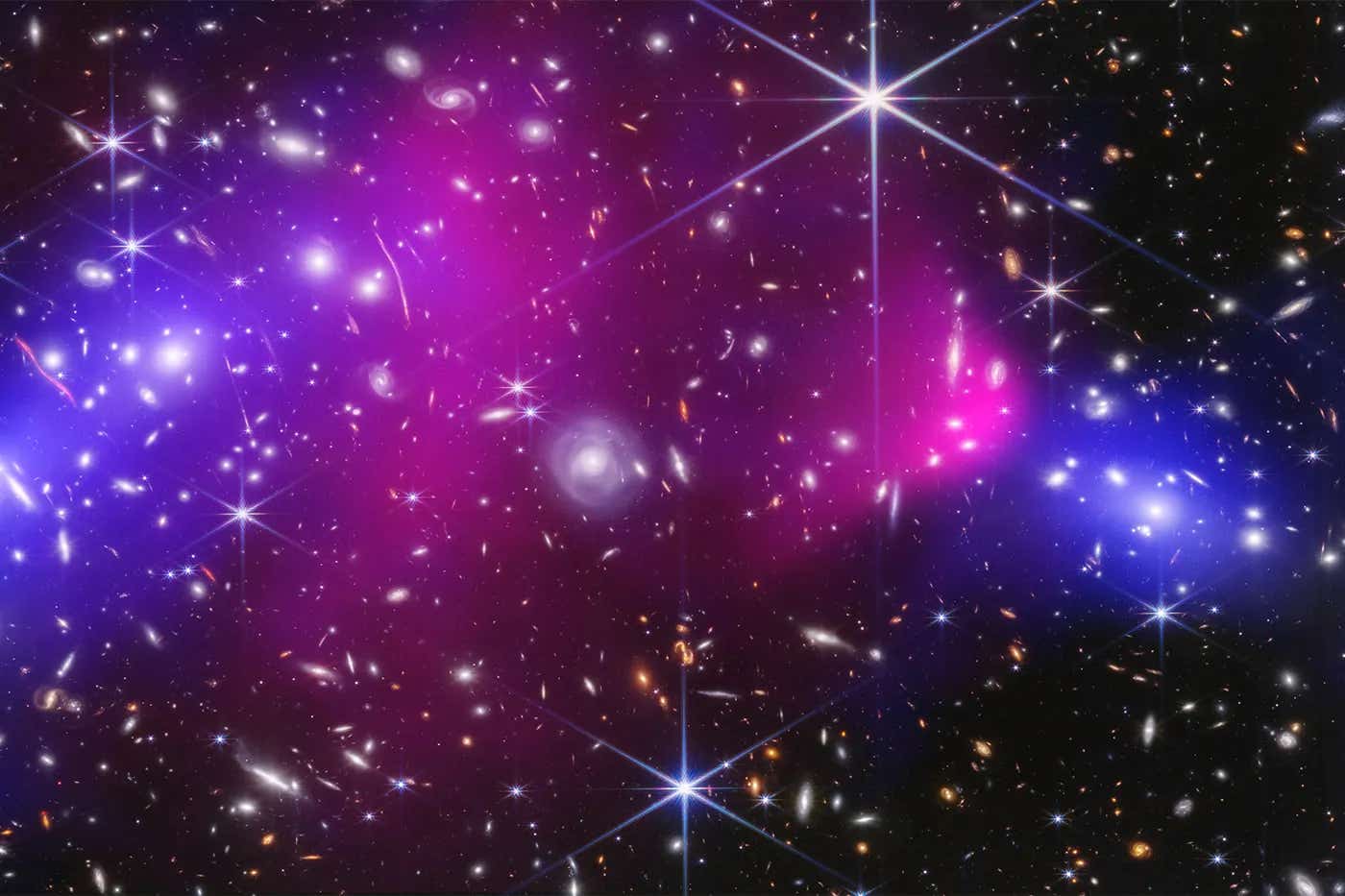

The Dark Energy Survey attempts to chart the force behind the universe’s accelerating expansion. (CREDIT: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, CXC)

Dark energy remains one of the most stubborn puzzles in modern science. Despite decades of observation and increasingly powerful telescopes, its true nature is still unknown. Now, scientists involved in the Dark Energy Survey, a six-year international project led by researchers from institutions including Northeastern University and supported by U.S. and global partners, have released their final results. The findings do not deliver a breakthrough explanation, but they narrow the field and sharpen the questions guiding future research.

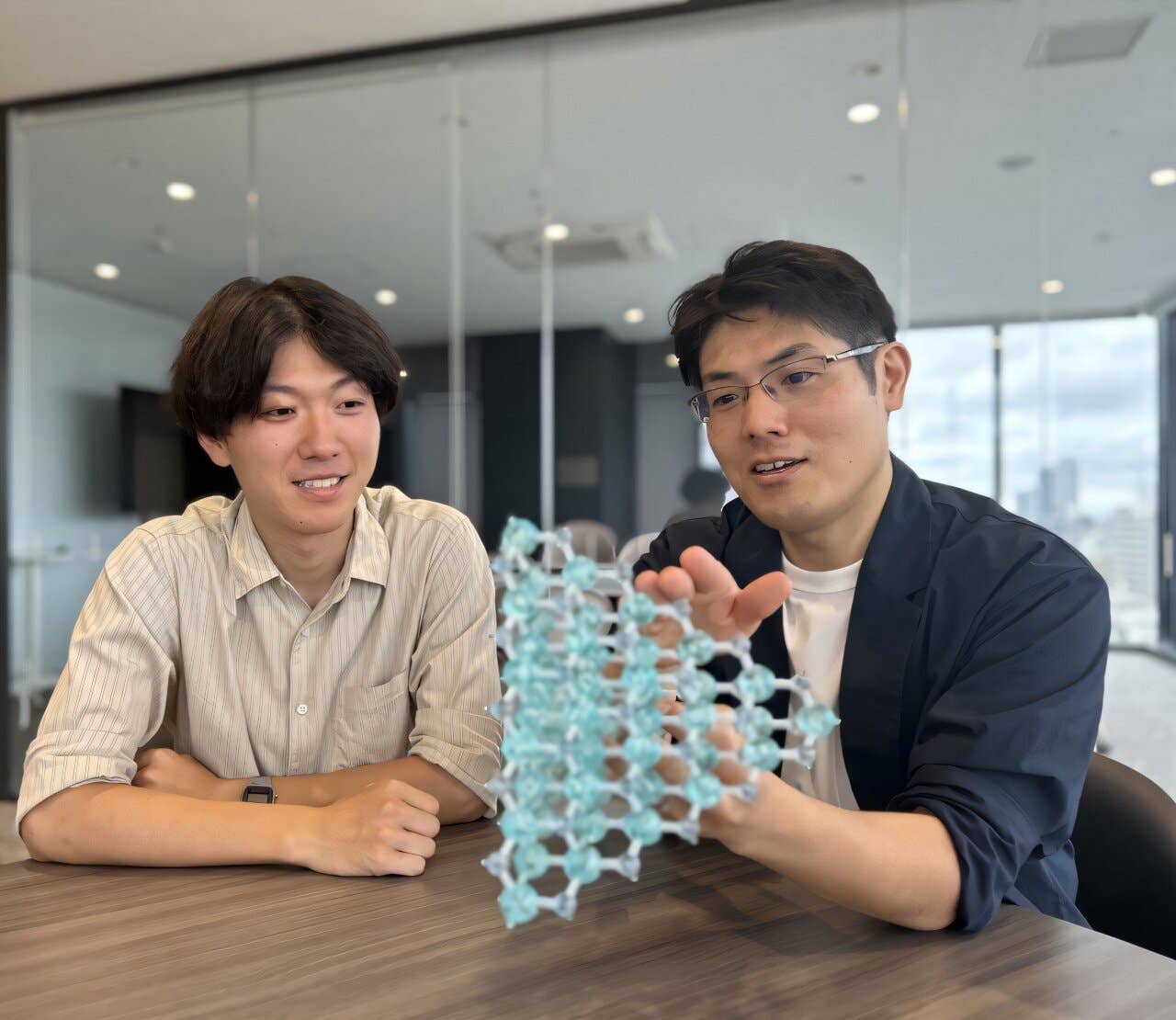

Jonathan Blazek, Northeastern University physics assistant professor and co-lead of the survey’s modeling and analysis team, indicates there is advancement made through precision. “While we've offered some hints as to what dark energy may be, we've yet to answer all of these questions,” said Jonathan Blazek. “What we do know is, better than ever before, what questions we should pursue and how to approach them.”

The survey of dark energy, commonly referred to as DES, was performed by an international group of more than 400 scientists. The six-year survey produced one of the most comprehensive catalogs available for future cosmology projects. It is now an essential resource for future cosmology research.

Why Should Anyone Care About Dark Energy?

About 13.8 billion years ago, the universe started to expand during a process called the Big Bang. Following this initial expansion, gravity slowed the expansion of the universe. However, in 1998, researchers on two separate research teams independently found surprising results from their studies of distant exploding stars. Approximately 9 billion years after the Big Bang, the expansion of the universe began to accelerate.

"The unexpected acceleration suggested there is a force we cannot see, referred to as dark energy. We refer to it as “dark” because even though we cannot directly observe it, or at least we cannot currently directly see it, it appears to be acting in such a way that it is separating the universe’s components. Most objects that have gravity are attractive and tend to pull things closer together. Therefore, dark energy is the opposite of what we would expect based on our current understanding of how gravity works," Blazek explained to The Brighter Side of News.

According to NASA, about 68 to 70 percent of the universe is made up of dark energy, while ordinary matter, the materials that comprise stars, planets, humans, and more, makes up only about 5 percent of it. The balance of the universe is made up of dark matter, an additional form of matter we cannot see and can only detect by its effect on matter through gravity.

Testing Competing Models of the Universe

Most cosmological theories currently support the idea of dark energy being a constant characteristic of the universe, as represented by the cosmological constant in the ΛCDM model of cosmology. Some competing models of cosmological evolution suggest dark energy could vary slowly over time. To test these competing models, scientists need extensive datasets that can be analyzed statistically. Therefore, the Dark Energy Survey provides this.

Developed to effectively collect data that could potentially help scientists prove or disprove the presence of dark energy is the Dark Energy Camera, or DECam, built specifically for the Dark Energy Survey. The DECam has 570 megapixels of digital camera capability and was constructed by the United States Department of Energy at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. It was mounted on a four-meter telescope operated by the National Science Foundation and located in Chile.

The telescope was used by the Dark Energy Survey to obtain observational data over the course of 758 very long nights between 2013 and 2019. This effort provided data on 669 million galaxies, as far away as billions of light-years, from all over the universe. The survey covered roughly one-eighth of the universe’s observable area.

Mapping the Universe in Unprecedented Detail

The data led to the creation of the most extensive and detailed map of the universe created to date. “I believe that this is extremely significant,” stated Martin Crocce, the co-coordinator for the DES analysis. “This usage is unique to this generation of dark energy experiments.”

DES used many techniques instead of relying on a single measurement. Astronomers combined observations of galaxy groups with measurements of how gravity from galaxies distorts other galaxies, a phenomenon known as weak gravitational lensing. These approaches were used together to determine galaxy distribution.

You can make a map of “invisible matter.”

Gravitational lensing is one of the most important pieces of information in producing these findings. Massive objects bend the light of objects located in the background, causing slight distortions. By measuring these distortions, astronomers can determine how much mass exists along the path of light, even though that mass cannot be seen directly.

Precision Measurements and What They Reveal

“You can make a map from gravitational lensing and find out where the matter is located in the universe,” said Blazek.

Utilizing advanced statistical techniques, the DES scientists combined the positions of galaxies, shapes of galaxies, and lensing signals within the same statistical measurement, referred to as a “3x2 Point.” By bringing together this large amount of data, they were able to provide more precise measurements than in previous DES analyses. The accuracy nearly doubled after analyzing data from the final six years of observations.

From the complete analysis, scientists evaluated different possible models for explaining the existence of dark energy. One model assumes it is constant throughout time, with no change in strength. Another model allows for variable strength throughout the history of the universe but does not vary over time. The consistency of the DES measurements with previous results is a strong indication of this finding.

The results show that the measurements are consistent with the most commonly used types of dark energy. Without giving evidence for a change of dark energy over time, the data remain consistent with the cosmological constant, the simplest explanation currently available in cosmology.

What Comes After the Dark Energy Survey

“We get the same type of answer time after time, regardless of the uncertainty associated with our measurements,” stated Blazek. “You answer some questions. You have ruled out some possibilities.”

In conjunction with this, the measurements have also provided one of the best depictions of the large-scale distribution of matter within the universe to date. Although there are mild differences between the large-scale matter distribution observed by DES and that seen in measurements of the cosmic microwave background, these differences are not statistically significant enough to overturn current models.

The Dark Energy Survey, by releasing its final dataset to the public, has reached the end of its scientific program. However, the impact of this program is only beginning to be seen. The majority of researchers involved with DES are now working on the next generation of scientific experiments, which will collect significantly more data than DES was able to obtain.

Ending One Era and Beginning Another

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, also located in Chile, is expected to build on DES by conducting the Legacy Survey of Space and Time. In addition, space-based missions such as the European Space Agency’s Euclid mission and NASA’s Roman Space Telescope are designed to perform further high-precision measurements of dark energy.

“The end of the DES is the transition of power to the next generation,” said Blazek. “Scientifically, there is a legacy associated with this. Our work has had an enormous influence and is training us for future generations.” It really feels like an era is ending and a new one is beginning.

Research findings are available online in the journal arXiv.

Related Stories

- 10 billion-year-old supernova sheds new light on cosmic expansion and dark energy

- Dark matter and dark energy may not exist, new research finds

- UChicago astrophysicists believe dark energy may be evolving

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.