Early hominins walked on two legs 7 million-years-ago, study finds

3D scans of a 7-million-year-old femur reveal a key ligament attachment; strong evidence Sahelanthropus walked on two legs.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

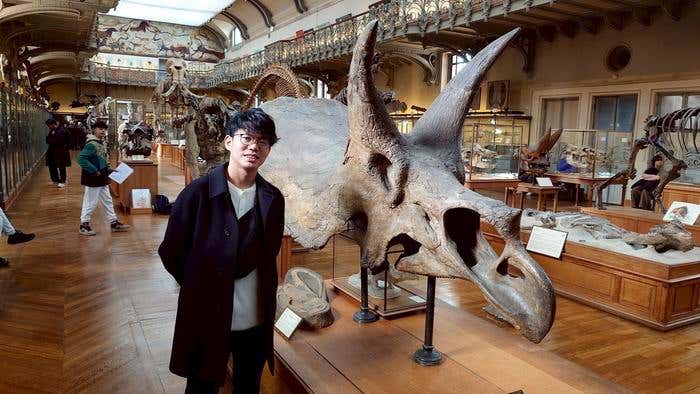

A reconstruction of Sahelanthropus tchadensis. (CREDIT: dctim1/Flickr)

A seven-million-year-old skull found in Chad sits at the center of a long argument about human origins. The species, Sahelanthropus tchadensis, was announced in the early 2000s as a possible early hominin. That label matters because it would place upright walking close to the split between the human line and the chimpanzee and bonobo line.

Now a team led by Scott Williams, an associate professor in New York University’s Department of Anthropology, says the strongest evidence yet comes from a different part of the body: a thigh bone. The group also included researchers from the University of Washington, Chaffey College, and the University of Chicago. Their findings appear in Science Advances.

At issue is bipedalism. If Sahelanthropus regularly walked on two legs, it fits more cleanly within the human lineage. If not, it may belong closer to other ancient apes, or even represent a mix that is harder to classify.

“Sahelanthropus tchadensis was essentially a bipedal ape that possessed a chimpanzee-sized brain and likely spent a significant portion of its time in trees, foraging and seeking safety,” said Williams. “Despite its superficial appearance, Sahelanthropus was adapted to using bipedal posture and movement on the ground.”

Reading bones in 3D

Sahelanthropus was discovered in Chad’s Djurab desert by University of Poitiers’ palaeontologists. Early work focused on the cranium. Later reports described limb bones found with the material, including parts of the femur and ulnae. Those later publications fueled doubt. Some researchers argued the limb bones looked ape-like, or even questioned whether the bones belonged to the same species.

"The new study leans on two approaches. First, the team compared many traits in the ulnae and femur to the same bones in living primates and fossil species. Second, they used 3D geometric morphometrics, a method that measures shape in fine detail. The comparisons included Australopithecus, a well-known early human ancestor that lived roughly four to two million years ago and helped cement the idea that upright walking came before large brains," Williams explained to The Brighter Side of News.

"In overall shape, the results may sound surprising. Both the ulna and the femur look most similar to Pan, the genus that includes chimpanzees and bonobos. Yet we believe that broad resemblance is not the full story. In our view, a lower limb can still preserve clear signals tied to upright posture, even when the forelimb reflects climbing and other tree-based behavior," he continued.

The team also tested whether the ulnae and femur likely “match” in size. Using breadth measures from each bone, they found a strong correlation between ulna and femur size. That pattern supports the idea that the bones could come from the same individual or similarly sized individuals.

Why one small bump matters

The central claim rests on three features in the femur that the authors say are hard to explain without bipedal walking.

First is a femoral tubercle, a small raised area linked to the iliofemoral ligament. That ligament is the strongest in the human body and helps stabilize the hip during upright standing and walking. The study reveals that this tubercle has so far been identified only in hominins. In Sahelanthropus, the researchers report a preserved tubercle that extends from the greater trochanter region and fits the expected attachment pattern.

Second is a natural twist in the femur, called femoral antetorsion, that helps the legs point forward. The fossil does not preserve the ends of the bone used in many clinical measurements, so the team calculated a torsion angle using planes on the shaft surface. The result, they reported, places the specimen with hominins rather than with great apes, which often show the opposite pattern.

Third is the gluteal complex. The study reported butt muscle attachment features that resemble early hominins and support hip stability during standing and walking. The team also noted what is missing. Some structures common in chimpanzees do not appear in this specimen, while a gluteal ridge and a feature interpreted as a gluteal tuberosity do appear.

The researchers added a fourth line of support from proportions. Apes tend to have long arms and short legs, while hominins trend toward longer legs. Sahelanthropus still looks closer to Pan than to humans, but it shows a relatively long femur compared with its ulna. The team argued this pushes the animal away from a purely ape-like body plan and toward a “mosaic” suited to both trees and ground travel.

“Our analysis of these fossils offers direct evident that Sahelanthropus tchadensis could walk on two legs, demonstrating that bipedalism evolved early in our lineage and from an ancestor that looked most similar to today’s chimpanzees and bonobos,” concluded Williams.

Practical Implications of the Research

These findings reshape how you can think about the earliest steps toward being human. If Sahelanthropus truly combined chimpanzee-like climbing with meaningful adaptations for upright walking, then bipedalism may have started as a flexible strategy, not a sudden switch.

That matters for future fossil work because it shifts what researchers look for. Instead of expecting a clean, human-like walking package right away, teams can test for smaller, targeted features that reveal how hips and knees handled body weight.

The study also offers predictions that can guide field searches. If future discoveries uncover a pelvis from this species, the authors expect an intermediate design between chimpanzees and later hominins. Clear, testable predictions like that help move debates from opinion toward evidence.

Over time, this kind of work can refine timelines for when key traits emerged, and it can sharpen how museums, textbooks, and educators explain human origins to the public.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

Related Stories

- Two ancient cousins of Lucy walked on two legs in different ways

- Million-year-old fossil changes what we know about human hands and feet

- 1.5 million-year-old footprints from two different co-existing human species found in Kenya

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.