Early humans started making and using tools 2.75 million years ago

New research reveals 300,000 years of steady stone toolmaking in Kenya, between 2.75 and 2.44 million years ago.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

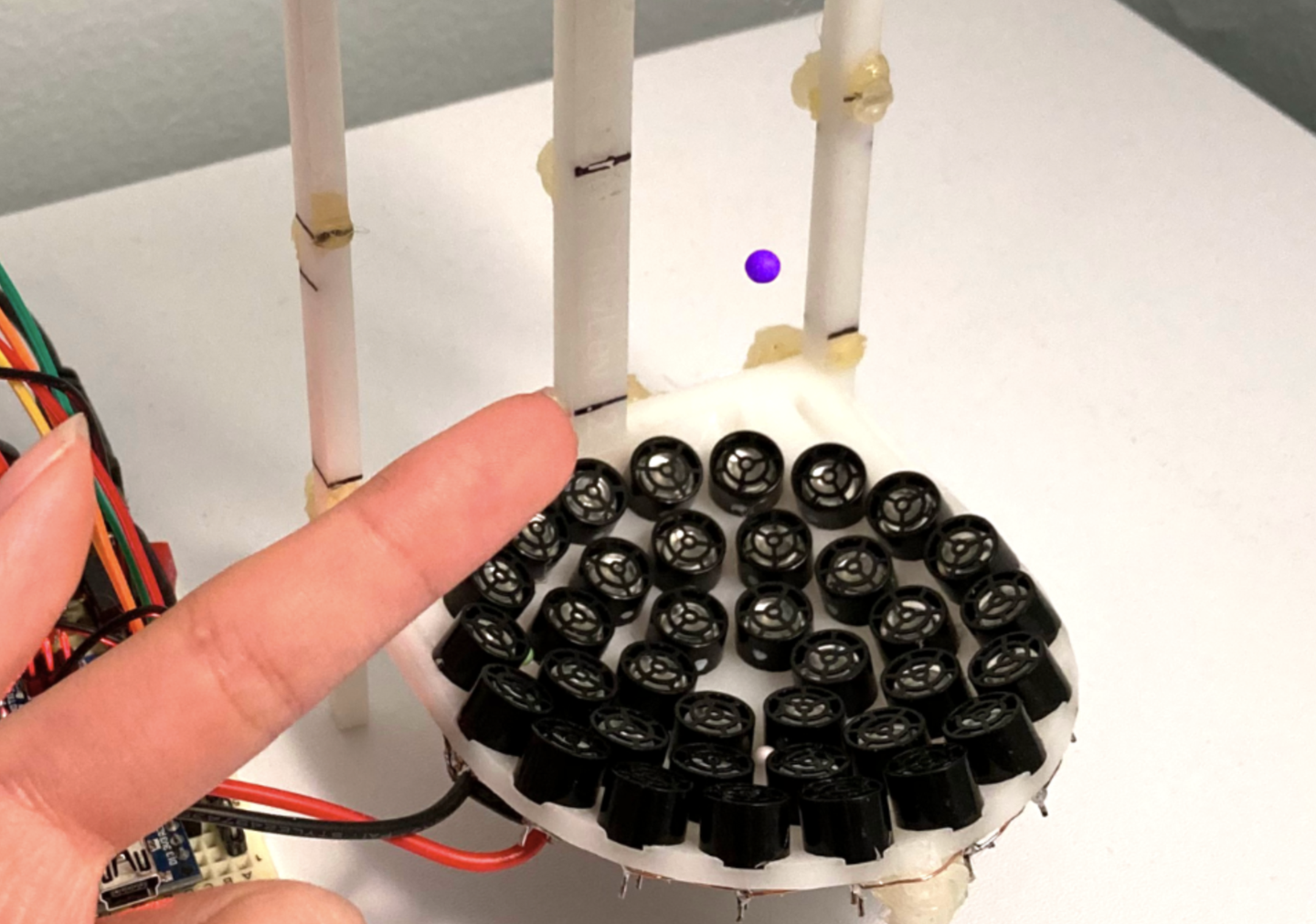

The evidence shows that early hominins returned to the same area again and again between 2.75 and 2.44 million years ago. (CREDIT: Wix)

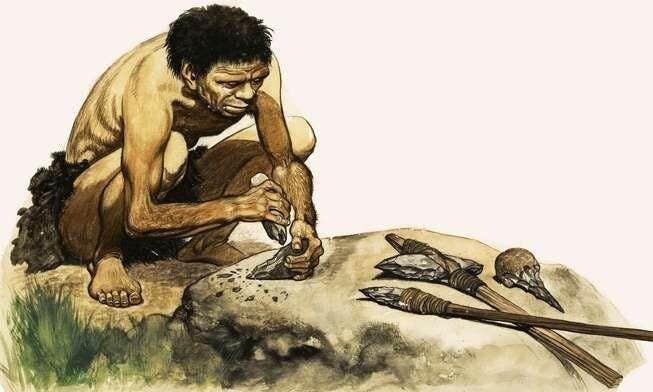

Long before cities or farms, the earliest humans were standing in a changing northern Kenyan landscape, striking stone to stone with steady hands. Their world was noisy with wind, heat, wildfires, and frightened animals moving across open grasslands.

Through all of that, they continued to make sharp flakes that cut flesh from bone and opened difficult plants. When you see this ancient work, you can imagine the sensation of living amid hunger and risk and long droughts, while still clinging to a familiar tool that aided in survival.

A newly discovered archaeological site in the Turkana Basin called Namorotukunan now gives you a rare invitation to peek into that long length of time. The evidence is a return of early hominins over and over again to the same spot between 2.75 and 2.44 million years ago.

They not only experimented, but they also stuck with the basic toolkit for nearly 300,000 years. That long period of commitment is changing how researchers think about the onset of stone technology and an early leap towards the modern human mind.

An Older History of the Oldowan Way of Life

Additional Oldowan sites older than 2.6 million years provide only brief glimpses. Namorotukunan is different; the three separate horizons, spaced across thousands of generations, have almost identical tool-making patterns. You see mostly sharp flakes and simple stone cores. Between 79.4 and 94.2 percent of the artifacts are in those two forms, which suggests that cutting edges were extremely important.

The people who made these tools were not yet advanced flintknappers. They turned the cores only a few times, but they were still adept at striking stones at consistent angles. They highly favored chalcedony and high-quality rocks to knap, which was rare in the local gravels. These choices facilitate imagining someone searching the riverbank, looking for the right stone, and returning to the relative safety of a riverbank to work on it.

The researchers recovered a total of 1,290 artifacts from the site. Even the smallest slivers of flake show clear characteristics of controlled knapping: percussion bulbs and distinct clean platforms. A few of the artifacts also exhibit butchery marks consistent with the 2.58-million-year layer, indicating that these tools had come into contact with animal tissue. These tools had been used to open carcasses, extract high-value nutritional resources, and expand a challenging diet in a challenging environment.

Rivers, Climate Shifts, and the struggle to survive

This life and landscape were volatile for the Turkana Basin during this time period. From around 2.8 to 2.7 million years ago, a wetter floodplain environment transitioned to a drier landscape provided primarily by seasonal river channels, with mean annual rainfall ranging from about 231 to 855mm.

The local flora shifted from broad, wetland plants to shrubs and grasses that were drier-adapted. Phytolith data indicate an increasing C4 vegetation, and plant-wax biomarkers support the proliferation of open grasslands. Microcharcoal counts indicate high-frequency fires. There is also local fauna: equids, antelope grazers, and open country pigs, contributing to the picture.

If you lived there, you would have felt the land drying underfoot. You may have observed rivers changing course, seen fire scourges ravage landscapes, or felt hot earth crack beneath your feet. And that very instability may have propelled early hominins deeper into tool dependence.

Sharp flakes allowed them to cut roots, slice tougher plants, and claim meat from both the objects of their hunt and from scavenging a deceased animal. Technology allowed early hominins to navigate instability and led to a life populated by loss and uncertainty.

Rivers were important for the above context. Braided channels that moved cobbles into the landscape had it in place about 2.7 million years ago, the same moment the earliest artifacts occur. Sediments from deeper in the stratigraphy lack these cobbles; therefore, prior capable ancestors likely did not make stone tools at this site. Access to raw materials provides opportunity.

Global forces also influenced future hominin technology. Once the Panama Seaway was closed, monsoon shift cycles and circulation changes made East Africa more arid. Those persistent and slow processes likely encouraged tool usage as a strategy of consistency for survival.

How researchers pieced together the story

The research undertaken was a very large, careful study. Between 2013 and 2022, every artifact found along the strata was excavated and mapped to millimeter accuracy. More than 275 cores were scanned in 3D and analyzed using morphometrics.

Geological profiles were logged and incorporated into a composite column. A series of volcanic ash bands was used to further assist in determining the ages of the objects; the magnetic field history was useful in confirming ages. Analytical investigations of soils, plant microfossils, and charcoal fragments proved useful for reconstructing climate histories.

“This site tells an amazing story of cultural continuity,” stated David R. Braun of the George Washington University and the Max Planck Institute, while Susana Carvalho of Gorongosa National Park referred to the site as “a rare lens to a changing world long gone.” Likewise, Dan V. Palcu Rolier of GeoEcoMar and Utrecht University observed that the team’s work suggests “the roots of one of our oldest habits: the use of technology to steady ourselves against change.”

Other researchers supported these sentiments. Niguss Baraki pointed out that the evidence suggests early technological skill, making sharp tools. Frances Forrest pointed to butchery marks on bones as evidence of increasingly expansive diets. Rahab N. Kinyanjui documented the stunning shift to a dry, fire-prone grassland where sustained toolmaking productivity occurred.

What the tools say about early resilience

Across all the lines of evidence, a specific narrative unfolds - during a time of radical climate fluctuations, early hominins secured their survival in a relatively reliable cutting technology. They repeated the same actions, struck the same rocks, and created the same flakes for hundreds of millennia. The simple act of carefully shaping sharp edges helped them adjust to the biologically humming, culturally local, and often biomechanically unyielding world.

Practical Implications of the Research

The research is evidence that long-term stability in a technology does not necessarily indicate stagnation. In fact, it may reveal a powerful fit between a working tool and the challenges of daily life.

This research provides a clearer timeline for the onset of stone tool technology and helps attribute early technology to climate pressures. The research also provides empirical evidence that resilience and adaptation played a role in shaping human behavior during the initial emergence of technology.

By tracing how early ancestors engaged with simple stone flakes to food-system disruptions, researchers can begin to gain insight into how modern humans may respond to changes in climate stressors.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Related Stories

- Ancient stone tools reveal how early seafarers from Asia became America’s first people

- Archeologists discover the first stone toolmakers from 2.9 million years ago

- 1.4 million year old stone balls reveal early human toolmaking abilities

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.