Early humans were prey, not predators, study finds

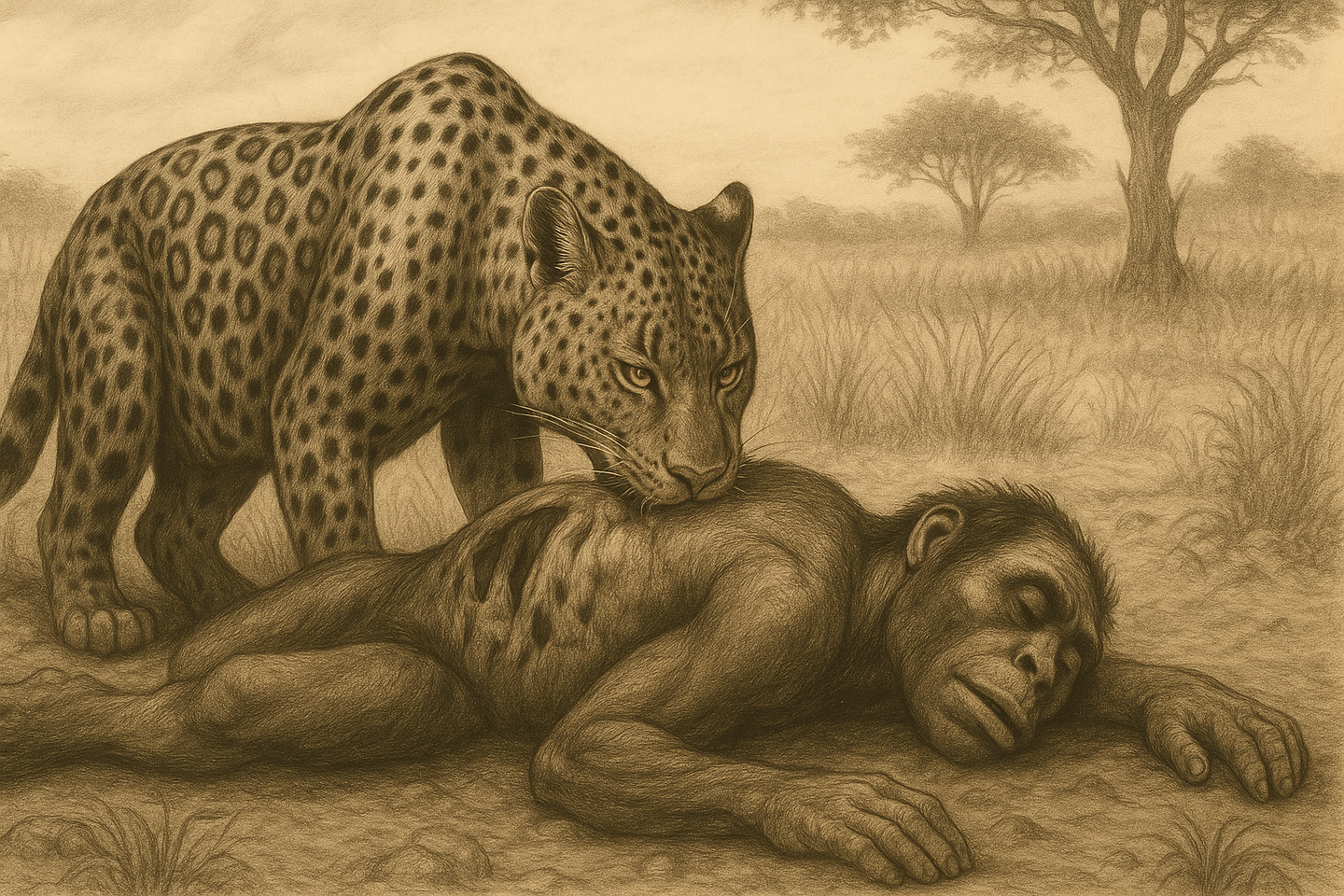

AI reveals Homo habilis was still hunted by leopards 2 million years ago, reshaping ideas about when humans became top predators.

A new study using artificial intelligence shows Homo habilis was still preyed upon by leopards 2 million years ago. (CREDIT: Rice University / YouTube)

For decades, textbooks painted a dramatic picture of early humans as tool-using hunters who rose quickly to the top of the food chain. The tale was that Homo habilis, one of the earliest representatives of our genus, was one of the first predators to dominate predators and lead humans down the path toward being top predators.

But new research that applies artificial intelligence indicates this ascent to power was much slower, more complicated, and much riskier than previously thought.

Research findings suggest that Homo habilis was not yet in control of its world 2 million years ago. Instead, the small-brained humans were still preyed upon, probably by leopards. That is, our ancestors remained vulnerable much longer than scientists have believed.

A Predator's Bite

The evidence comes from bones uncovered at Tanzania's Olduvai Gorge, a site that has yielded some of the most important human origins clues.

Anthropologists previously believed the markings on those bones were caused by tool use or scavenging. But the team led by Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo, an anthropologist at Rice University and co-director of Madrid's Institute of Evolution in Africa, wanted to test that assumption with new technology.

They taught machines in the guise of deep-learning algorithms to recognize the subtle tooth mark patterns of different carnivores. They supplied the system with thousands of samples, which learned to tell bites produced by lions, hyenas, wolves, crocodiles, and leopards apart.

When the AI scanned Homo habilis fossils at Olduvai, the findings were dramatic. "We found that these early hominids were consumed by other carnivores rather than taking over the landscape at the moment," Domínguez-Rodrigo explained. The leopard signature appeared repeatedly with strong confidence.

Rethinking the Balance of Power

This find disrupts the traditional narrative. Researchers, for many years, believed that around 2.5 million years ago, humans were capable of outsmarting large felines and hyenas by using stone implements and collective action. That would have been a transition from prey to predator.

But the bites have a different story to tell. Homo habilis, even though its brain was in development and it was making increasing use of tools, remained on the menu almost a half-million years later. "The origin of the human brain doesn't mean we knew everything right away," Domínguez-Rodrigo said. "This is a more nuanced tale. These early humans, these Homo habilis, were not the ones to effect that change."

Instead, the researchers suggest that the power balance shifted much more unevenly and gradually than was thought. Maybe it was Homo erectus, which existed alongside habilis, that played a larger role in the rise of human hunting dominance.

The Role of AI in Fossil Studies

What's new in this study is not so much the finding as the method. For many years, human scientists have simply looked at fossil bones, noting scratches, fractures, and dents and trying to decide whether the injury was caused by tools, predators, or natural forces. But where various predators leave corresponding tooth markings has always been a hypothesis.

Artificial intelligence flipped that on its head. Deep learning algorithms can now detect microscopic patterns that most scientists can't see and not only assert a predator was involved but which predator was involved. "AI is a game changer," Domínguez-Rodrigo said. "It's taking approaches that have been stable for 40 years past what we thought. For the first time, we can determine not only that these people were eaten but by whom."

It is now possible to associate bones with specific predators. Scientists are able to go back to collections of fossils from across Africa and the world to solve questions long in the making: When did hominids stop being prey? Where did they first become lords of their landscapes? Which predators were most deadly?

Living in a Dangerous World

The findings also reveal how Homo habilis might have lived their day-to-day lives. Since leopards were likely to hunt them, these early humans likely spent most of their time evading danger. They could have lived on hiding, scavenging leftovers, or hunting small prey instead of openly chasing big game. Their stone tools might have contributed to survival, but not sufficient to protect them from ambush cats.

Being prey influenced more than survival strategies—it impacted how our ancestors evolved. Ongoing threat from predators would have favored caution, cooperation, and accommodation. Rather than a simple ascent to dominance, the human story is more of an arduous struggle with fits and small victories.

A More Nuanced Past

The study also brings up new questions about the role of Homo erectus, with its larger brain and endurance runner body. Did erectus become top dog earlier, with cooperative hunting? Or did it occur even further along, with more advanced species? The evidence is still thin, but the leopard bites make one thing clear: Homo habilis was still not "king of the beasts."

Domínguez-Rodrigo and his co-researchers, Marina Vegara Riquelme and Enrique Baquedano, consider this research only the beginning. Supported by Spain's Ministry of Science and Innovation, Ministry of Universities, and Ministry of Culture, they hope to apply AI tools to other fossil records. Through patterns laid out over geospatiotemporal space, they hope to build a more comprehensive mosaic of when humans transitioned from being prey to becoming hunters.

"It is highly stimulating to be the first human being ever to lay eyes on something for the first time," Domínguez-Rodrigo said. "When you expose places that have been hidden from human eyes for more than 2 million years, you're contributing to how we reconstruct who we are. It's a privilege and highly stimulating."

Practical Implications of the Research

These findings alter the perspective on human evolution. Instead of a smooth leap from victim to predator, the process seems to be stumbling, full of vulnerability and accommodation. AI presents a grand new window for researchers to investigate ancient fossils and uncover information that was not visible earlier.

For human beings, this research is a reminder that flexibility and determination, and not brute dominance immediately, defined our ancestors. That perspective might be a model for survival, cooperation, and environmental studies today.

It also shows how new technology can shed new light on one of the very first mysteries about who we are and where we are from.

Research findings are available online in the journal Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

Related Stories

- Fossilized teeth reveal a risky diet change spurred human evolution

- Earth’s magnetic field failed 41,000 years ago - forever changing human evolution

- Surprising link between chimpanzee tool use and human evolution

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.