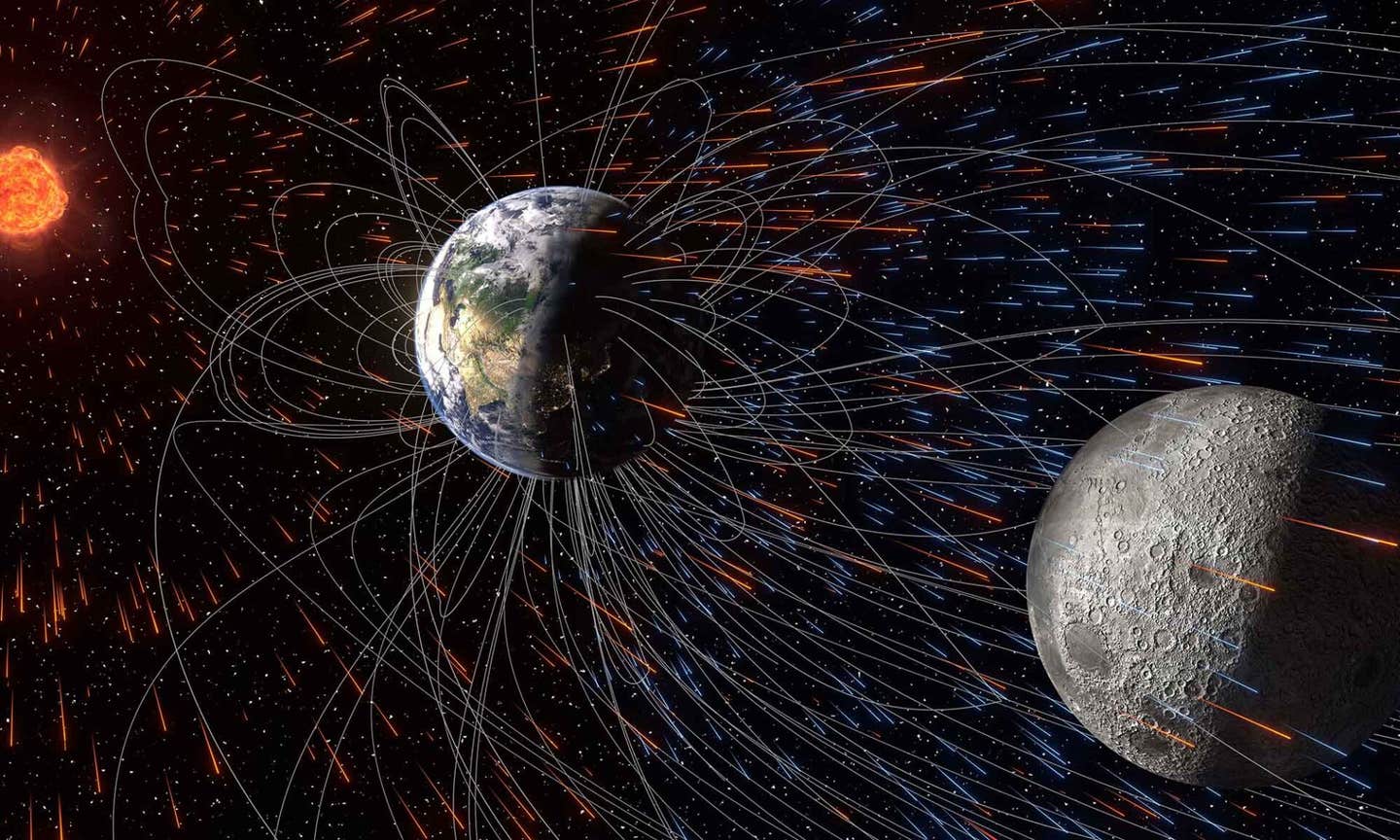

Earth’s magnetic field funneled atmospheric elements to the Moon over billions of years

New research suggests Earth’s magnetic field helped funnel atmospheric particles to the Moon, leaving chemical traces in lunar soil.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Study findings suggest the history of the terrestrial atmosphere, spanning billions of years, could be preserved in buried lunar soils. (CREDIT: Nature Communications Earth & Environment)

Lunar rocks are famously dry. They contain almost none of the volatile elements that easily escape into space, such as hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, and light noble gases. Yet those same elements appear in the Moon’s loose surface soil, known as regolith. Because they are largely missing from solid rock, their presence in soil points to sources beyond the Moon itself.

One obvious contributor is the solar wind. This steady stream of charged particles from the Sun directly strikes the lunar surface. It can explain some light elements, but it falls short for others. Nitrogen stands out. Lunar soils contain too much nitrogen, and its isotopic balance between nitrogen-15 and nitrogen-14 varies far more than expected from solar input alone. This mismatch became known as the lunar nitrogen conundrum.

Since the Apollo missions, scientists have proposed many explanations. Some suggested chemical sorting during lunar processes. Others pointed to comets, asteroids, or interplanetary dust. Cosmic rays can generate nitrogen through spallation, but measured amounts exceed what this process allows. These gaps suggested an extra-solar source, possibly closer to home.

Could Earth have seeded the Moon?

One long-standing idea is that Earth itself supplied some of these volatiles. Ions can escape Earth’s upper atmosphere and drift into space. Several studies proposed that this “Earth wind” could implant material into lunar soil. Earlier work linked this process to periods when Earth lacked a strong magnetic field, assuming a magnetic shield would block escape.

Spacecraft observations later complicated that picture. Instruments detected terrestrial ions flowing down Earth’s magnetotail, a long extension of the magnetic field on the nightside. Other research suggested this flow could help form lunar surface water. Yet many models did not track how Earth wind and solar wind mix or how ions escape in the first place.

A key question remained unresolved. Does Earth’s magnetic field block atmospheric loss, or can it help guide ions toward the Moon?

New research from the University of Rochester tackles that problem directly. The study appears in Nature Communications Earth and Environment. It combines detailed computer simulations with isotope data from Apollo samples to test how Earth’s atmosphere could have reached the Moon.

“By combining data from particles preserved in lunar soil with computational modeling of how solar wind interacts with Earth’s atmosphere, we can trace the history of Earth’s atmosphere and its magnetic field,” says Eric Blackman, a physics and astronomy professor at the University of Rochester and a scientist at its Laboratory for Laser Energetics.

Modeling winds from the Sun and Earth

The research team built a three-dimensional model that follows how solar wind flows past Earth and interacts with its atmosphere. The simulations include tracer particles that separate pure solar material from ions escaping Earth. They track both flows as they move toward the Moon over a full lunar month.

The team tested two main scenarios. One represents a modern Earth with a strong magnetic field and present-day solar wind. The other models an early Earth without a magnetic field, exposed to a much stronger young Sun. In both cases, the total atmospheric mass remains fixed, allowing direct comparisons.

As the Moon orbits Earth, it encounters different plasma environments. Most of the time, it sits in direct solar wind. At certain phases, it passes through shocked regions near Earth’s magnetic boundary. These crossings create peaks in particle flux that form a double-horned pattern over a lunar month.

Inside the magnetotail, solar wind intensity drops sharply. Earth wind ions appear only there. The simulations show that magnetic fields do not simply block escape. Instead, they stretch the upper atmosphere into a long tail, allowing ions to survive farther from Earth.

Under modern conditions, the average Earth wind reaching the Moon changes little whether Earth has a magnetic field or not. Under extreme solar wind pressure, however, a magnetic field can reduce escape by about an order of magnitude.

From bulk flows to isotope fingerprints

To connect these flows to real lunar samples, the team added a photoionization model. Solar ultraviolet and X-ray radiation ionize gases high above Earth, creating charged atoms of hydrogen, nitrogen, helium, neon, and argon.

The study introduces a hydrodynamic escape boundary. This boundary marks the lowest altitude where ions can escape and still match observed isotope ratios. Ions created above it are swept away by solar wind and carried into the magnetotail.

Once picked up, Earth wind ions mix with solar wind in a collisionless plasma. They accelerate to similar speeds and travel together toward the Moon. Some implant into the lunar nearside when it passes through the magnetotail. Over time, layers of soil record these arrivals.

The researchers treated lunar regolith as a mixture of two sources. One is pure solar wind. The other is non-solar material, modeled as Earth wind. Using mixing equations, they compared predicted isotope ratios to Apollo measurements.

For modern Earth conditions, the results matched well. Nitrogen and hydrogen data fit when the escape boundary lay below about 300 kilometers altitude. Helium, neon, and argon ratios also aligned, with best fits near 250 kilometers. These matches appeared across multiple isotope plots.

What the Moon reveals about Earth’s past

The early Earth scenario told a different story. With no magnetic field and a stronger solar wind, the simulations produced a mixture dominated by solar particles. Earth wind contributions fell short of explaining the non-solar fractions seen in lunar soil.

This contrast suggests that most terrestrial material reached the Moon during Earth’s long magnetized history, not during a brief unmagnetized phase. The magnetic field did not prevent escape. Instead, it helped channel ions along field lines that extend to the Moon.

One exception remains. Hydrogen in lunar soil cannot be explained by Earth wind alone. Its source likely includes solar or other external contributions.

“These results show the Moon carries a long-term record of Earth’s atmosphere,” says Shubhonkar Paramanick, a graduate researcher involved in the study. The findings also refine views of magnetic protection. A magnetic field can both shield and extend an atmosphere, depending on conditions.

"Taken together, the simulations and mixing analyses suggest that the Moon’s volatile inventory was built up mainly during Earth’s long-lived magnetized phase, not during any brief unmagnetized interval early in its history. The lunar soil appears to record a time when solar wind strength was closer to present conditions and Earth’s dynamo was active, allowing Earth wind ions to be carried down the magnetotail and implanted on the nearside," Eric Blackman told The Brighter Side of News.

Over billions of years, tiny amounts of Earth’s air appear to have settled onto the lunar surface. That quiet exchange left chemical clues that scientists are only now learning to read.

Practical Implications of the Research

The findings reshape how scientists view Earth’s magnetic field and atmospheric escape. They show that a magnetic field can guide particles into space rather than fully blocking them. This insight improves models of planetary habitability and atmospheric evolution.

Lunar soil may preserve a chemical archive of Earth’s past atmosphere. Studying it could reveal changes in climate, oceans, and biological conditions over deep time. The work also informs studies of Mars and other worlds that lost magnetic protection.

For future exploration, the research suggests lunar regolith contains more usable volatiles than once thought. Nitrogen and noble gases could support sustained human activity on the Moon. That reduces reliance on supplies from Earth and strengthens plans for long-term lunar missions.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

Related Stories

- Scientists discover new planet-wide electric field that is fundamental to Earth's atmosphere

- Surprising new study finds that Earth’s atmosphere can clean itself

- Earth’s atmosphere may be source of some lunar water

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a Nor Cal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.