Every self-help book ever, boiled down to 11 simple rules

[July 25, 2020: Mashable] The first self-described self-help book was published in 1859. The author’s name, improbably, was Samuel…

[July 25, 2020: Mashable]

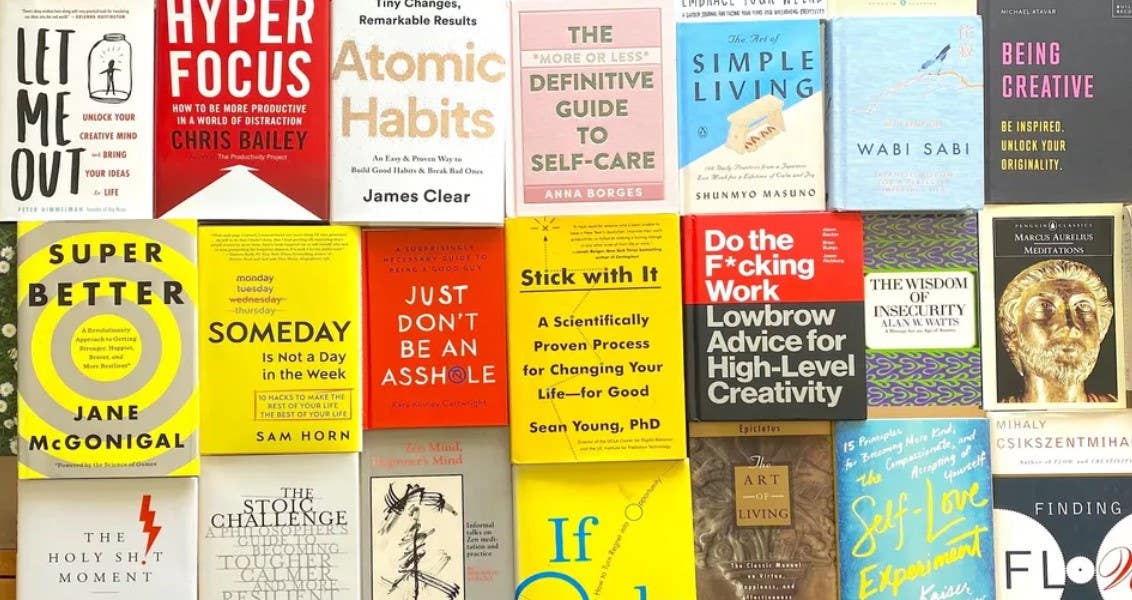

The first self-described self-help book was published in 1859. The author's name, improbably, was Samuel Smiles; the title, even more improbably, was Self-Help. A distillation of lessons from the lives of famous people who had pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, it sold millions of copies and was a mainstay in Victorian households. Every generation since had its runaway bestseller, such as How to Live on 24 Hours a Day (1908), Think and Grow Rich (1937), or Don't Sweat the Small Stuff (1997).

By now, the $11 billion self-help industry is most definitely not small stuff. Yet when you strip it down, there's very little new information. After all, we were consuming self-help for centuries before Smiles, just under different names. Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius gave tweet-sized advice in Meditations; so did Benjamin Franklin in Poor Richard's Almanack. Even self-help parody isn't new. Shakespeare did it with Polonius' "to thine own self be true" speech in Hamlet: basically a bullet-point list from a blowhard.

The 21st century has seen a measure of self-awareness about our self-help addiction. There's the wave of sweary self-help bestsellers I wrote about, such as The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck. They hover somewhere between parody and dressing up the same advice as their forebears in earthier language. More recently, there's a trend you might call meta-self-help: books in which people write about their experiences following self-help books, such as Help Me! (2018) and How to Be Fine (2020), based on the similar self-help podcast By the Book.

But hey, if it's all pretty much the same stuff — and it is — why stop at distilling it into a single book? Why not condense the repeated lessons of an entire genre into one article? That's what I've attempted here, after reading dozens of history's biggest bestsellers so you don't have to. Here is the essence of the advice I've seen delivered again and again.

Like these kind of stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

1. Take one small step.

Your daily habits aren't just important; they're the whole ballgame. Aristotle knew this when he wrote "we are what we repeatedly do." And despite your natural desire to fix everything at once, the best way to get big results is to make tiny, continuous changes to daily habits. In Japan, this is known as kaizen, a concept introduced to American readers in Stephen Covey's 1989 bestseller The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

Habit adjustment got a lot of help in the 21st century from groundbreaking studies into human behavior. These are outlined in the 2014 bestseller The Power of Habit. Then came Atomic Habits (2018), which points out that improving any metric by one percent at a time adds up to exponential growth over the long term. What matters in the short term is the repetition, which takes your behavior out of the limited realm of willpower and makes it automatic.

Personally I like the summary in Mini Habits (2013): Make your daily practice "too small to fail." Ensure you exercise for five minutes every day, for example, and you'll soon find yourself eager to do more.

2. Change your mental maps.

Time to enter the world of sports cliché. "If you believe it, the mind can achieve it": These motivational-poster words are attributed to the NFL's Ronnie Lott, but also reflect what nearly every self-help book has tried to tell us since The Power of Positive Thinking (1952). In achieving any goal, basically, you have to thoroughly visualize your preferred end result, then work backwards in precisely-planned steps.

The planning part is key. Take it away.... MORE