Fermilab experiment finds no evidence for a fourth neutrino, ending a long-debated theory

Fermilab’s precision MicroBooNE experiment finds no evidence for a fourth neutrino, closing a long-debated theory.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

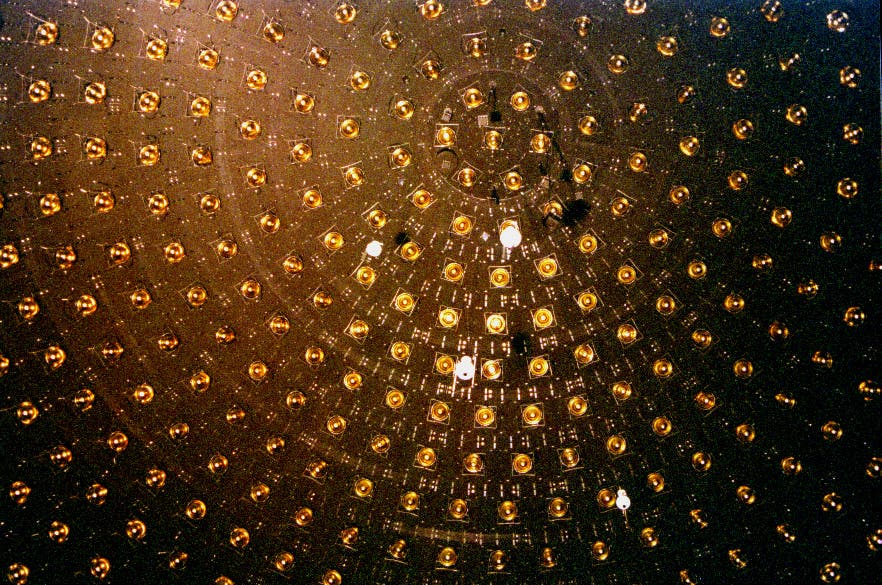

The inside of the MiniBooNE neutrino detector. A precision test at Fermilab finds no sign of a fourth neutrino, ruling out the simplest sterile model. (CREDIT: Wikimedia / CC BY-SA 4.0)

For three decades, a riddle has followed neutrinos, the near-weightless particles that stream through Earth by the trillions each second. They change identities as they fly, shifting among three known types: electron, muon and tau. That shape-shifting is supposed to be fully explained by the Standard Model of particle physics. Yet a handful of experiments kept hinting the story might not be complete.

Those earlier measurements suggested neutrinos were flipping identities too quickly, over distances that felt too short for the known rules. A bold idea took hold: maybe a fourth kind of neutrino existed. This extra particle, unlike the others, would not feel the weak force and would be almost impossible to detect directly. Physicists called it sterile. If real, it could help explain dark matter and reveal new forces at work.

Now one of the most careful tests yet says that simple answer does not fit the evidence.

An international team working at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory reported in Nature that the MicroBooNE experiment has found no sign of a fourth neutrino. The result rules out the simplest version of the sterile idea with about 95 percent confidence.

“We know that the Standard Model does a great job describing a host of phenomena in the natural world,” said Matthew Toups, a Fermilab senior scientist and co-spokesperson for the experiment. “And at the same time, we know it’s incomplete. It doesn’t account for dark matter, dark energy or gravity.”

MicroBooNE does not solve those mysteries. But it closes one promising path toward them.

Why the sterile idea was tempting

Neutrinos move in three “flavors,” yet each flavor is made from a blend of three tiny masses. As the mix shifts during flight, the flavor you detect can change. Experiments at power plants, with cosmic neutrinos, and on particle beams have confirmed the math behind that dance.

Trouble started in the 1990s. At Los Alamos National Laboratory, a detector called LSND saw a hint that muon neutrinos were turning into electron neutrinos faster than they should. Years later, Fermilab’s MiniBooNE experiment reported a similar glow of extra electron-like events. On the reactor side, a few short tests saw fewer electron neutrinos than expected.

A single new particle could patch the holes. Add one more mass, let it mix slightly with the three known types, and you might explain both the excesses and the shortages. Because measurements of the Z boson proved only three neutrinos take part in the weak force, the newcomer had to be invisible to that force. Hence, sterile.

The catch was never theory. It was consistency. Some experiments saw hints, others saw nothing. The picture never fully lined up.

Inside a detector that can tell electrons from impostors

MicroBooNE was built to cut through that fog. It sits in Illinois, bathed in neutrino beams from two directions. The device is a tank of liquid argon wired like a camera, able to trace the path and energy of every charged particle sparked by a passing neutrino. Unlike older detectors, it can tell an electron from a photon with high accuracy.

That matters. MiniBooNE could not always tell whether a shower came from an electron or a gamma ray. MicroBooNE can. It also views two beams at once: a nearby beam with few built-in electron neutrinos, and an off-axis beam with many more. If extra neutrinos were appearing or disappearing, the two beams would not mislead the detector in the same way.

Researchers divided millions of interactions into 14 detailed samples, including electron events, muon events and neutral pions that mimic electrons. They then used the richer muon data to fine-tune expectations for electron counts and to pin down uncertainties in the beams and detector.

What the data say

When the team compared predictions with what the detector saw, the simplest answer fit best. The three-neutrino model matched the energy patterns in all four main electron samples from both beams. Statistically, the agreement was strong.

Allowing a sterile neutrino into the math did not help. The fit barely improved. In formal tests, the standard model of three neutrinos still won.

The consequences are direct. The new limits wipe out the region that once looked promising after LSND. They erase most of the territory suggested by MiniBooNE. Reactor hints also lose ground under the new measurements.

Two quirks in the data even tightened the noose. One beam showed a slight dip in electron candidates, which works against any extra appearance. The other showed more muons than expected, shrinking the error bars on predicted electrons. Together, they push the sterile idea further into a corner.

The hunt goes on

The team is careful not to declare victory over every exotic option. More complex models, with several new particles or unusual decays, remain on the table. And MicroBooNE has more data to analyze.

At Fermilab, two additional argon detectors have joined the same beam, forming the Short Baseline Neutrino program. With three checkpoints instead of one, future studies will watch neutrinos change across distance in finer detail.

Justin Evans, a University of Manchester professor and another co-spokesperson, summed up the moment: “They saw flavor change on a length scale that is just not consistent with there only being three neutrinos. And the most popular explanation over the past 30 years to explain the anomaly is that there’s a sterile neutrino.”

Then came the turn. “With this latest result we’ve closed one door, but the anomaly still remains unexplained. The simplest answer is now ruled out, which means the real explanation could be far more exciting. At Columbia, we’re racing to explore whether neutrinos might be our portal into an entirely hidden ‘dark sector’, one of the last remaining viable explanations,” said Mark Ross-Lonergan of Columbia University.

Ten members of the Columbia Neutrino Group, led by Georgia Karagiorgi, Ross-Lonergan and Mike Shaevitz, helped guide simulations, steer the analysis and vet the results before publication.

For now, one mystery survives intact, while a neat solution falls away.

The Three Confirmed Neutrino Flavors

There are three verified types of neutrinos, confirmed by particle physics experiments over several decades. They’re called flavors, and each is linked to a matching charged particle:

- Electron neutrino (νₑ)

- Associated with the electron.

- Produced in huge numbers by the Sun and in nuclear reactors.

- First detected in the 1950s.

- Muon neutrino (ν_μ)

- Associated with the muon (a heavier cousin of the electron).

- Commonly produced in cosmic ray interactions and particle accelerators.

- Discovered in 1962.

- Tau neutrino (ν_τ)

- Associated with the tau particle (even heavier than the muon).

- Hardest to detect because it requires very high energies to produce.

- Experimentally confirmed in 2000.

One Key Twist: They Change Identity

Neutrinos can oscillate between flavors as they travel. An electron neutrino created in the Sun can arrive at Earth as a muon or tau neutrino. This behavior proves neutrinos have mass, which was a major discovery because the Standard Model originally assumed they were massless.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Related Stories

- Neutrinos may hold the key to solving the universe’s biggest secrets

- Strange neutrino interactions could change how stars die, study finds

- Physicists record the most precise neutrino mass measurement ever

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.