Florida house cat named Pepper helped researchers discover new strain of virus

A Florida virologist’s cat brought home a shrew, leading to the discovery of a new virus strain with unknown risks to animals and people.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

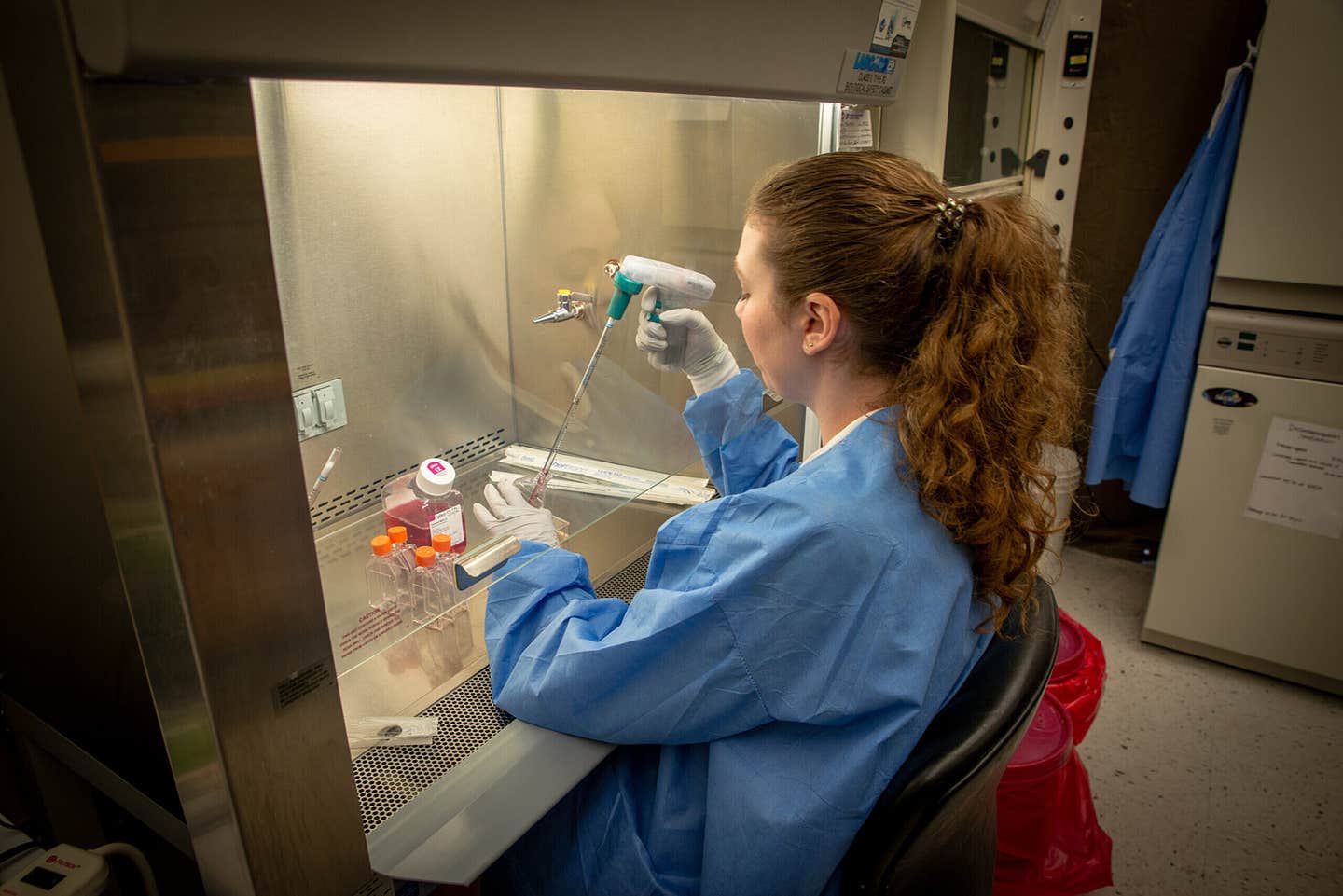

Scientists identify a new orthoreovirus strain in a shrew caught by a cat in Florida, raising questions about cross-species virus spread. (CREDIT: Andy Williams)

In a laboratory in Florida, a house cat named Pepper has again been involved in the unanticipated discovery of a new virus as a result of its habit of bringing home dead mammals. This time, it was a dead shrew.

What looked like a simple backyard casualty turned out to be a scientific breakthrough. Inside the animal, researchers identified a new strain of a virus that could have implications for both animals and people.

A Surprise Inside the Shrew

Pepper, the cat belonging to virologist Dr. John Lednicky at the University of Florida, is no stranger to discovery. Last year, Pepper helped to lead the scientists to the first known case of a jeilongvirus in the U.S. Pepper's most recent contribution to research was in bringing home an Everglades short-tailed shrew, prompting another round of testing, which uncovered new findings.

The shrew was not just a shrew but was shown to contain an unidentified strain of mammalian orthoreovirus, a family of viruses known to infect a considerable variety of mammals, including humans, bats, and deer. The strain was later identified and named Gainesville shrew mammalian orthoreovirus type 3 strain UF-1.

Dr. Lednicky is a research professor at the University of Florida's College of Public Health and Health Professions and is affiliated with the Emerging Pathogens Institute. His original focus was on mule deerpox virus, and then, through this discovery, more complicated research efforts began.

Although orthoreoviruses are not new to the scientific community, they were once labeled orphan viruses and did not appear to be associated with disease. However, recent research has indicated that they could contribute to respiratory, stomach, and brain diseases.

In isolated instances, these viruses have been associated with severe illnesses in children, such as encephalitis, meningitis, and gastroenteritis. "At the end of the day, we need to begin to understand orthoreoviruses, and we need to learn how to detect these viruses quickly," said Lednicky.

Not a one-time discovery

This new virus did not just a one-time fascination but is simply another virus in the soccer laboratory's growing viral list from the last few years. The team has also described two other novel viruses they discovered in farmed white-tailed deer. One virus was described in 2019 and exhibited near-identical genes to an orthoreovirus found in minks in China and also an ill lion in Japan.

That unexpected result left scientists baffled. How could the same strain of virus — or at least one that had the same genes — arise in animals that were completely separated by continents? One hypothesis that arose was that animal feed could be the vector, because the animals came from the same supplier, despite being on different continents.

Like the influenza virus, orthoreoviruses can genetically mix in situations where two strains co-infect the same cell. This mixing is termed reassortment and can generate novel viral strains. The fact that these viruses can change quickly is enough to track.

As noted by Emily DeRuyter, the study's principal author and a Ph.D. candidate from the university's One Health program, it represents only one piece of the puzzle. "Mammalian orthoreoviruses were previously assumed to be 'orphan' viruses, present in mammals, including humans, but not causing illness," explained DeRuyter. "More recently, these viruses have been associated with respiratory, central nervous, and gastrointestinal disease."

The entire genetic coding sequence of the newly identified virus was reported in the journal Microbiology Resource Announcements, a peer-reviewed avenue for short reports of genome data for microbial species.

The Bigger Picture: Why These Viruses Matter

The discovery of Gainesville shrew mammalian orthoreovirus type 3 strain UF-1 is important not because it poses an immediate danger to human health, but because of what it reveals about the underlying viral world. With so many mammals sharing viruses, understanding how infections start, circulate, and transmit is critical. Even though a new strain has not been shown to cause disease in humans, it remains uncertain.

The orthoreovirus group consists of many strains, and each strain might impact species differently. In some cases, a virus might have mild or even "invisible" effects. In other cases, particularly if a virus is capable of swapping genes with all or part of another virus's genome, the effects might be more severe.

The evolution of viruses in this manner indicates that even strains which are benign today could be harmful at a future date. "If you look, you will find, and that’s why we are constantly finding new viruses," said Lednicky.

The concern is that there is still much we don’t know about the behavior of these viruses or how they circulate in a host species or transmit to other species. Do the viruses spread via ingestion---eating, contact--- dirtying their hands or paws? or do they spread via insects in the air? In the end, there are more questions than answers.

What is next for the researchers?

For Gainesville orthoreoviruses, the next steps are serology and immunologic studies to determine if the virus poses a risk to humans, pets, or wildlife. Researchers will look for evidence of past infections by testing blood samples, and will also better understand immune responses.

Although these types of studies take time, the sequencing discovery is already informing their future research. The plan is to establish better early detection and understand the potential threats posed by these viruses before they pose a threat.

Lednick's approach to virus discovery is both practical and passionate. "This was just an opportunistic study," he said, "If you have an animal die, why not test it before you just bury it? You can gain a lot of knowledge." So far, that attitude has paid off. With some help from a curious cat and some incredibly skilled lab work, a tiny dead shrew was turned into an example of a new chapter of viral evolution.

As for Pepper, the furry scientist-in-residence remains alive and healthy. After he ventured outdoors, there were no signs of illness in him. He may not know it, but with every new find he brings, the researchers are closer to understanding the puzzle of the viruses that move from animals to people.

Research findings are available online in the journal Microbiology Resource Announcements.

Related Stories

- Common plant virus shows stunning results in targeting and destroying cancer cells

- Breakthrough new vaccine protects against Zika virus while preventing serious side effects

- Tiny alpaca nanobody blocks two deadly human viruses, study finds

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Mac Oliveau

Writer

Mac Oliveau is a Los Angeles–based science and technology journalist for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication focused on uplifting, transformative stories from around the globe. Passionate about spotlighting groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, Mac covers a broad spectrum of topics including medical breakthroughs, health and green tech. With a talent for making complex science clear and compelling, they connect readers to the advancements shaping a brighter, more hopeful future.