Giant dinosaur was a “heron from hell”, study finds

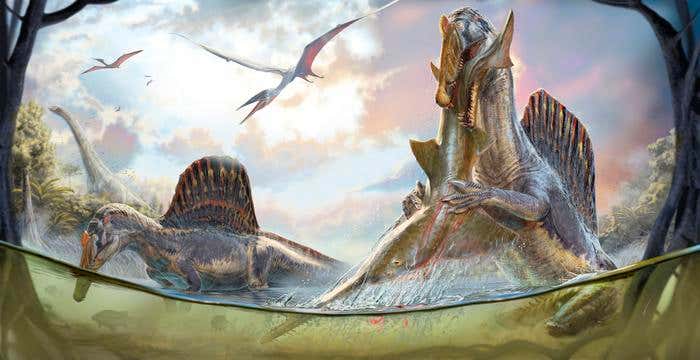

Controversy has surrounded the hunting habits of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, a sail-backed dinosaur from the Cretaceous era.

Controversy has surrounded the hunting habits of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, a sail-backed dinosaur from the Cretaceous era. (CREDIT: Daniel Navarro)

Controversy has surrounded the hunting habits of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, a sail-backed dinosaur from the Cretaceous era. As one of the largest predators ever known, its lifestyle—whether it was an aquatic dweller diving deep for prey or a shoreline predator snatching meals from shallow waters—has intrigued scientists for years.

A recent study led by paleontologists from the University of Chicago seeks to shed light on this debate by analyzing the bone density of Spinosaurus, offering new insights into its aquatic behavior.

The discussion on whether Spinosaurus was a deep-water swimmer or a shoreline predator has been ongoing. Initial descriptions of a nearly complete Spinosaurus specimen in 2014 portrayed it as a creature adept at stalking shorelines or swimming on the surface, rather than a fully aquatic predator.

The Spinosaurus thigh bone (left) was thin sectioned with a diamond saw (middle) to reveal under magnification its bone structure (right). (CREDIT: Stephanie Baumgart and Evan Saitta)

However, in 2020, an international team of researchers suggested in a study published in Nature that Spinosaurus propelled itself underwater akin to an eel, challenging the earlier interpretation.

Building upon this, a 2022 study published in Nature by many of the same researchers provided further evidence supporting the idea that Spinosaurus had dense bones, enabling it to dive like a penguin. They also proposed that other spinosaurids, such as Suchomimus, may have been waders rather than deep divers.

To delve deeper into these hypotheses, a team of paleontologists from UChicago, in collaboration with researchers from other institutions, conducted a study published in eLife in 2022. Using digital models, they found that both Spinosaurus and Suchomimus would have been unstable when swimming at the surface and too buoyant to fully submerge.

Related Stories

Now, this same team, led by senior author Paul Sereno from UChicago and first author Nathan Myhrvold, Founder and CEO of Intellectual Ventures, has revisited the question of bone density in Spinosaurus.

Their study, titled “Diving dinosaurs? Caveats on the use of bone compactness and pFDA for inferring lifestyle,” was published in PLOS ONE.

Sereno explained their approach: “We made thin sections of these species for bone density calculations, but encountered various factors that led to a range of values, undermining previous conclusions.”

Variation of Cg at different points along a single Nothosaurus dorsal rib. (CREDIT: PLOS)

The team addressed new questions regarding bone density, including methods for digitizing thin sections and considerations for selecting bone samples. They highlighted the complexity of understanding bone density, particularly in extinct species, where factors such as air sacs and body mass must be considered.

Collaborating with Myhrvold, the team reevaluated the statistical technique used in previous studies, known as phylogenetic flexible discriminant analysis (pFDA). Myhrvold emphasized the importance of addressing statistical prerequisites and ensuring consistent comparisons for accurate results.

Pneumatic features in the dorsosacral column in spinosaurids. (A) Suchomimus tenerensis (MNBH GAD500) precaudal column and pelvic girdle showing pneumatic features in (B) D2 in lateral view with coronal (B1) and axial (B2) CT cross sections, (C) D13 in lateral view with axial (C1) and sagittal (C2, 3) CT cross sections, and (D) S2 in ventral view with axial (D1) and coronal (D2) CT cross sections. (CREDIT: PLOS)

“This technique requires sufficient data and careful comparisons, which were lacking in earlier studies,” Myhrvold noted. “As a result, previous conclusions did not withstand scrutiny.”

The findings of their study aim to guide paleontologists in avoiding pitfalls associated with broad statistical analyses like pFDA. Sereno stressed the importance of using objective criteria and considering measurement errors and individual variations when assessing bone density.

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus precaudal column and pelvic girdle showing pneumatic features in (F) ~D2 in lateral, anterior, and dorsal views with coronal (F1, 2) and axial (F3) CT cross sections, (G) ~D6 in dorsal and lateral views showing coronal (G1) and axial (G,2, 3) CT cross sections, (H) ~D8 in dorsal and lateral views with axial (H1) and coronal (H) CT cross sections, and (I) S3 centrum in ventral and lateral views with coronal (I1) and axial (I2) CT scan sections. (CREDIT: PLOS)

“We believe Spinosaurus relied on extra bone strength to support its weight on its hind limbs,” Sereno commented. “It likely waded into waterways, anchoring itself in the mud to ambush prey, rather than diving deep.”

The study offers valuable insights into the aquatic behavior of Spinosaurus, underscoring the need for rigorous methodology and careful interpretation in paleontological research.

For more science stories check out our New Discoveries section at The Brighter Side of News.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News under a Creative Commons license. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.