Groundbreaking water-driven gear works without teeth or direct contact

NYU researchers develop gears that use fluid instead of teeth, offering flexible, durable alternatives to traditional mechanics.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

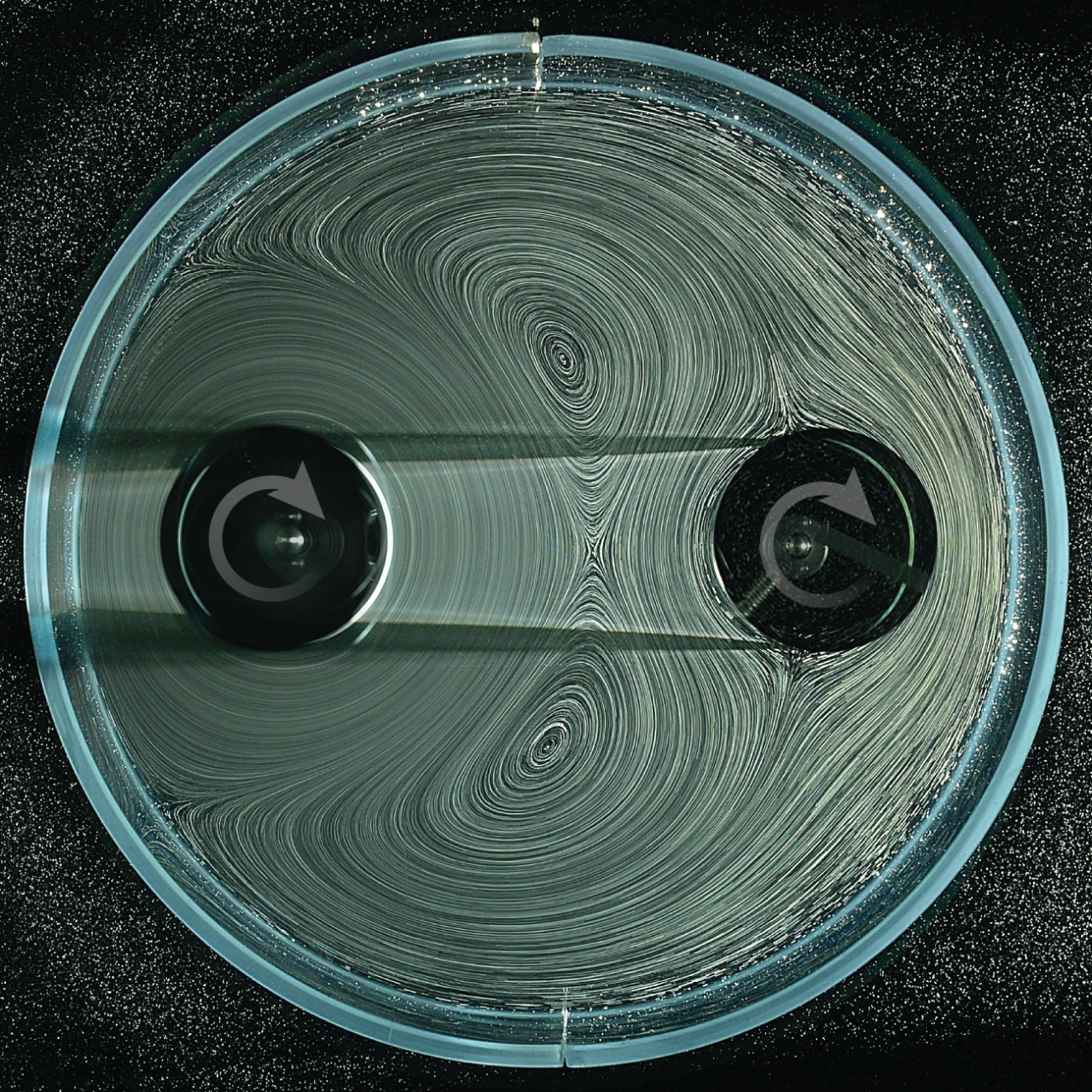

Two spinners inside a circular container and surrounded by liquid with bubbles that help to visualize the flows. The left spinner is actively driven to rotate with a motor (not shown) and the right one passively rotates due to the flows. (CREDIT: NYU’s Applied Mathematics Laboratory)

Scientists at New York University and NYU Shanghai have developed a new kind of gear that works without teeth or direct contact. Instead of metal parts locking together, the system relies on flowing liquid to transfer motion. The work, led by Jun Zhang, a professor of mathematics and physics at NYU and NYU Shanghai, appears in the journal Physical Review Letters and points to a different way of thinking about one of humanity’s oldest mechanical tools.

“We invented new types of gears that engage by spinning up fluid rather than interlocking teeth—and we discovered new capabilities for controlling the rotation speed and even direction,” Zhang says.

Gears have existed for roughly 5,000 years. Early versions appeared in ancient China, where they helped guide chariots across the Gobi Desert. Since then, gears have powered devices from the Antikythera mechanism of ancient Greece to clocks, windmills, and modern robots. Yet traditional gears share a weakness. Their solid teeth must align perfectly. Even minor defects, dirt, or wear can cause jamming or breakage.

That limitation pushed Zhang and his colleagues, Leif Ristroph, an associate professor at NYU’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, and Jesse Etan Smith, an NYU doctoral researcher, to ask a simple question. Could a gear-like system work without teeth or even physical contact?

Turning fluid into a mechanical link

The researchers turned to fluid motion for an answer. Air and water already drive turbines and propellers, so the team wondered if carefully shaped flows could also transmit rotation between objects. In their experiments, they placed two identical vertical cylinders, called rotors, into a thick glycerol-water mixture. One rotor was actively driven by a motor. The other was passive and free to move.

Tiny air bubbles were added to the liquid so the researchers could see how the fluid moved. By adjusting the distance between the cylinders and the speed of the driven rotor, the team tracked how liquid motion transferred force from one cylinder to the other.

At close distances and low speeds, the behavior resembled familiar gears. Fluid trapped between the cylinders acted like invisible teeth, causing the passive rotor to spin in the opposite direction of the active one. This counterrotation matched expectations.

But as conditions changed, the behavior shifted in surprising ways.

When gears behave like belts

At higher speeds or larger separations, the fluid no longer stayed confined between the rotors. Instead, it wrapped around the outside of the passive cylinder. In that case, the passive rotor began spinning in the same direction as the driven one, similar to a belt connecting two pulleys.

“Regular gears have to be carefully designed so their teeth mesh just right, and any defect, incorrect spacing, or bit of grit causes them to jam,” Ristroph explains. “Fluid gears are free of all these problems, and the speed and even direction can be changed in ways not possible with mechanical gears.”

This switch from opposite rotation to same-direction rotation did not depend on the system’s history. When researchers increased or decreased the driving speed, the outcome depended only on the current setup. That reliability matters for practical designs.

A simple setup reveals complex physics

Although the experiment used only two cylinders, the results speak to a larger mystery in fluid physics. Scientists have long known that moving objects influence one another through surrounding liquids. Schools of fish, swarms of bacteria, and even wind turbines interact through swirling flows. Yet most studies focus on objects moving through space, not spinning in place.

By reducing the problem to two rotors, the NYU team isolated how rotation alone drives interaction. The tall shape of the cylinders ensured the flow stayed mostly two-dimensional, making it easier to interpret.

What emerged was a detailed map showing when the system behaves like gears, when it behaves like belts, and when the passive rotor does not move at all. Small changes in spacing, speed, or confinement could flip the direction of rotation.

Competing forces in the flow

"Closer analysis showed why these flips happen. Fluid sliding along the inner side of the passive rotor tends to push it one way. Fluid sweeping around the outer side pushes it the opposite way. The rotor’s motion depends on which effect is stronger," Zhang told The Brighter Side of News.

"At very small gaps, the inner shear region shrinks, letting outer flow dominate and causing same-direction rotation. At intermediate gaps, inner shear regains control, restoring counterrotation. At larger distances, the overall flow pattern reorganizes again, flipping the outcome once more," he continued.

Speed also plays a prove role. Faster spinning increases inertial effects in the fluid. Instead of looping tightly, the flow spirals outward, weakening inner shear and strengthening outer shear. Once that balance tips, the passive rotor reverses direction.

Why this matters beyond the lab

The findings show that even the simplest rotating systems can behave in unexpected ways. They also suggest new design paths for machines that must work in harsh or confined environments, where traditional gears struggle.

Because fluid-based gears do not touch, they resist wear and tolerate misalignment. Their behavior can also be tuned on the fly by changing speed or spacing, something solid gears cannot do.

Practical Implications of the Research

This research could influence future designs in robotics, soft machines, and micro-scale devices where flexibility and durability matter.

Fluid-based gears may work better in dusty, wet, or sealed environments where solid parts fail. At smaller scales, similar principles could help engineers control microscopic rotors used in medical or chemical applications.

The study also provides a clearer framework for understanding how rotating objects interact in fluids, which could improve models of wind farms, biological systems, and engineered swarms.

Research findings are available online in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Related Stories

- Scientists create microscopic machines powered by light

- New bladeless wind turbine generates clean, quiet, bird-safe power

- Russia patents a modular spacecraft designed to create artificial gravity

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.