How a young Jupiter saved Earth from falling into the Sun

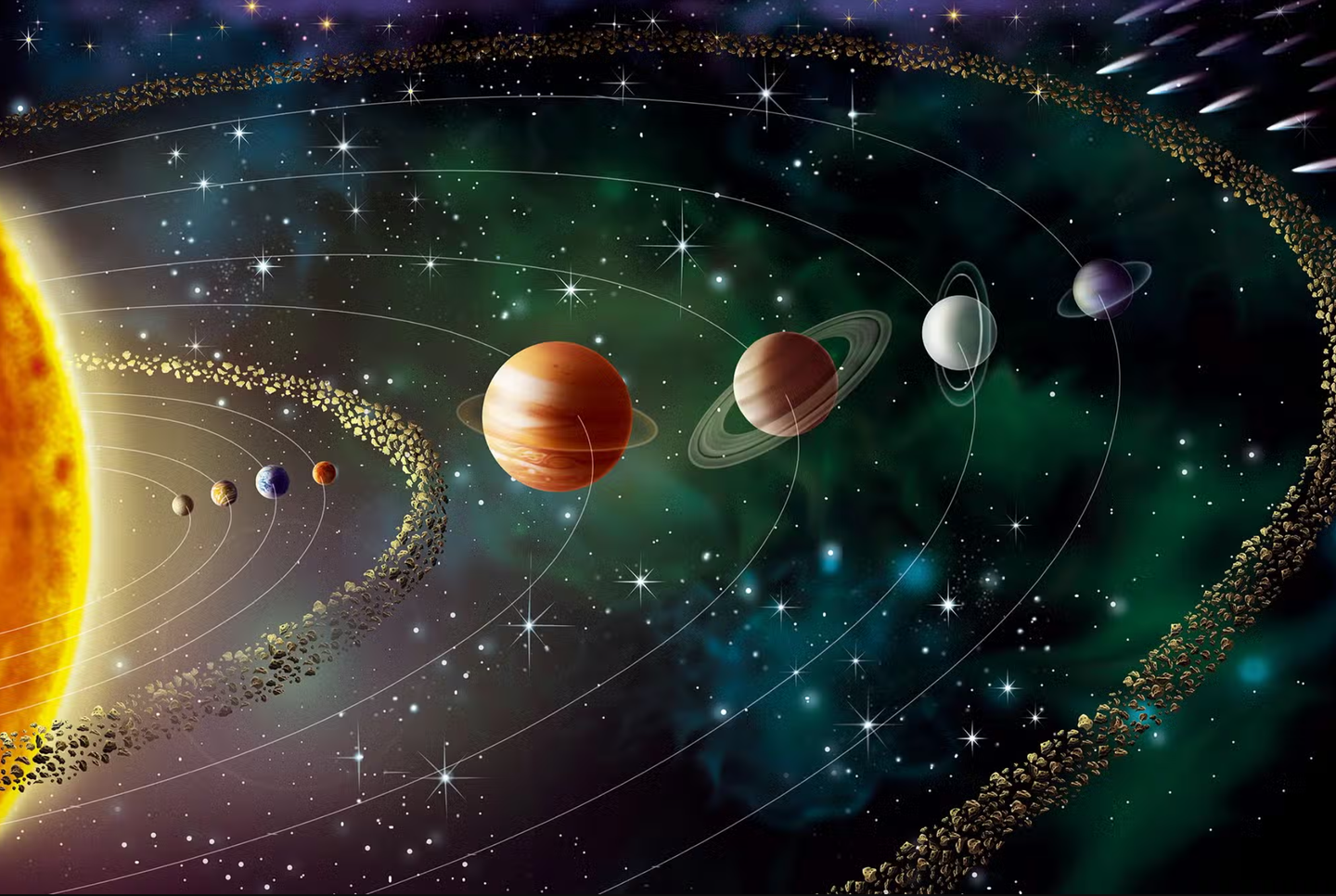

Jupiter’s early growth shaped Earth’s formation by trapping dust, forming rings, and protecting planets from spiraling into the Sun.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

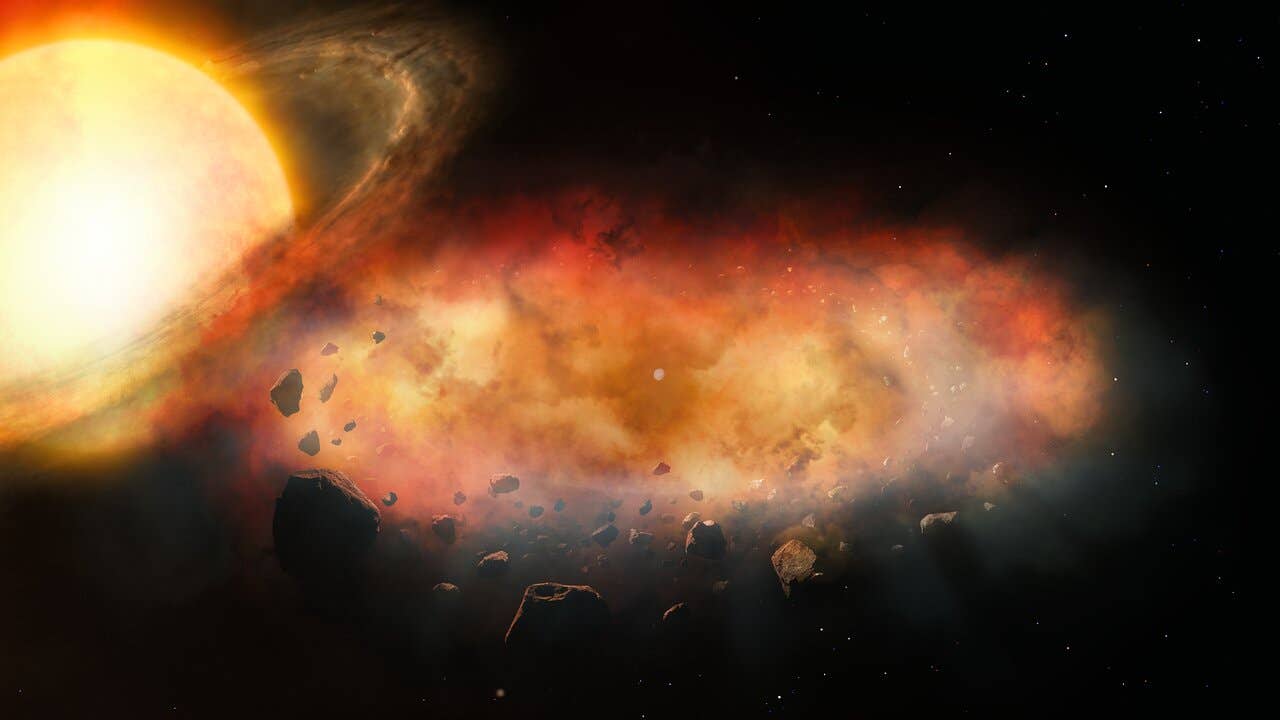

Jupiter’s early growth shaped Earth’s formation by trapping dust, forming rings, and protecting planets from spiraling into the Sun. (CREDIT: Wikimedia / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Not all of the solar system's building blocks formed simultaneously. Some of the first solid bodies, or planetesimals, formed in the first million years after the Sun was born. Others, including the parent bodies for ordinary and enstatite chondrites, two types of stony meteorites, took another two to three million years to form. Scientists couldn't explain the delay for decades.

The recent Rice University research finally offers an explanation, showing how juvenile Jupiter defined the solar system and rewrote its destiny.

How Jupiter Redefined the Solar System

Using the aid of sophisticated computer models, planetary scientist André Izidoro and Baibhav Srivastava modeled how Jupiter's initial rapid growth reshaped the disk of dust and gas that had formed around the Sun. What they discovered, say a paper in Science Advances, is that Jupiter grew not simply into a gas giant—Jupiter grew into a solar system builder.

Because Jupiter's enormous gravity pulled gas, it generated waves in the Sun's protoplanetary disk that featured spiral shock waves that formed a profound gap. They swept gas into the Sun like cosmic super-brooms, speeding its eviction from the inner system. In low-viscosity disks, this occurred in only 300,000 years—seven times faster than without Jupiter. That early clearing prevented young planets from straying too close to the Sun and getting lost, allowing Earth and Venus to remain around 1 astronomical unit (the distance between the Earth and Sun) away.

At the same time, Jupiter's gravity carved out rings and "pressure bumps" that served as dust traps. These were regions where drifting particles could settle instead of spiraling inward. These traps, in time, became fertile ground for new planetesimals—the rocky seeds of planets—to form long after the initial ones had already emerged.

The Mystery of Late-Born Meteorites

The study connects two ancient mysteries: why some meteorites formed millions of years later than others and how Earth-like planets were clustered together in the habitable zone. The solutions are found in meteorites known as chondrites. They are among the most primitive material ever found, having preserved minute molten droplets called chondrules and chemical signatures of the early solar system.

Chondrites are solar system birth capsules of the early times," said Izidoro. "The question has been: Why did some of these meteorites form so late, 2 to 3 million years after the first solids? Our results show that Jupiter itself created the conditions for their late birth."

As planetesimals and embryos formed early on and collided, they produced a steady shower of dust and debris. That material flowed inward until it hit the pressure humps carved out by Jupiter. There, the dust rained in to the densities where gravity could make it coalesce into a new generation of planetesimals—just in the 2 to 3 million-year window stored in chondritic meteorites.

A Stable Neighborhood for Rocky Planets

Jupiter's influence went far beyond dust traps. The planet's early formation also shaped the orbits of rocky worlds. Without Jupiter, simulations predict many young worlds would have migrated into the Sun and been lost. But Jupiter's early existence created "zero-torque zones," regions where inward migration slowed or stopped. That allowed rocky embryos to stay close to 1 astronomical unit and build the stable neighborhood where Earth, Venus, and Mars would eventually thrive.

Baibhav Srivastava explained that this interaction between gas flow, dust trapping, and planet migration solves two problems at once. "Jupiter formed early, opened a gap in the gas disk, and the process also protected the inward-outward solar system material separation," he explained. "It created new regions where planetesimals could form much later too.".

The model also explains why the solar system lacks the tightly grouped strings of tiny, close-in planets that are common in other star systems. Jupiter's gravitational shield cut off the flow of solids and gas pouring inward, preventing new planets from being formed close to the Sun.

Lessons from Other Star Systems

The new findings verify high-resolution pictures captured by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. ALMA astronomers spotted striking ring-and-gap features encircling youthful stars—likely a sign of giant planets being formed. Those images reveal what may have happened in our own solar system over more than 4.5 billion years ago.

"Watching those youth disks, we see the giant planets form and their birth place redrawn," Izidoro said. "The same was true in our own solar system. Early development of Jupiter deposited a signature we can perhaps still read today in the meteorites that rain down on Earth."

Practical Implications of the Research

This research changes everything scientists think about the ancient solar system. The early formation of Jupiter not only made it the largest planet—it determined the ordering of all the others. Its gravity protected the early Earth from being absorbed by the Sun, and its pressure stops recycled dust and debris into new worlds.

The findings can also inform the structure of other planetary systems. By identifying similar rings and gaps in young stellar disks, scientists can infer the presence of giant planets that are not visible and watch how they shape the development of smaller, possibly habitable planets.

Ultimately, the study provides a blueprint for how planetary systems such as Earth are created—and why life-bearing planets could be scarce throughout the universe.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

Related Stories

- How old is Jupiter? Tiny molten spheres embedded in meteorites have the answer

- Jupiter was once double its current size, study finds

- Jupiter’s colorful clouds are different than scientists previously thought

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.