How did massive elliptical galaxies appear so early after the Big Bang

A collapsing protocluster seen 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang shows how giant ellipticals may form fast.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

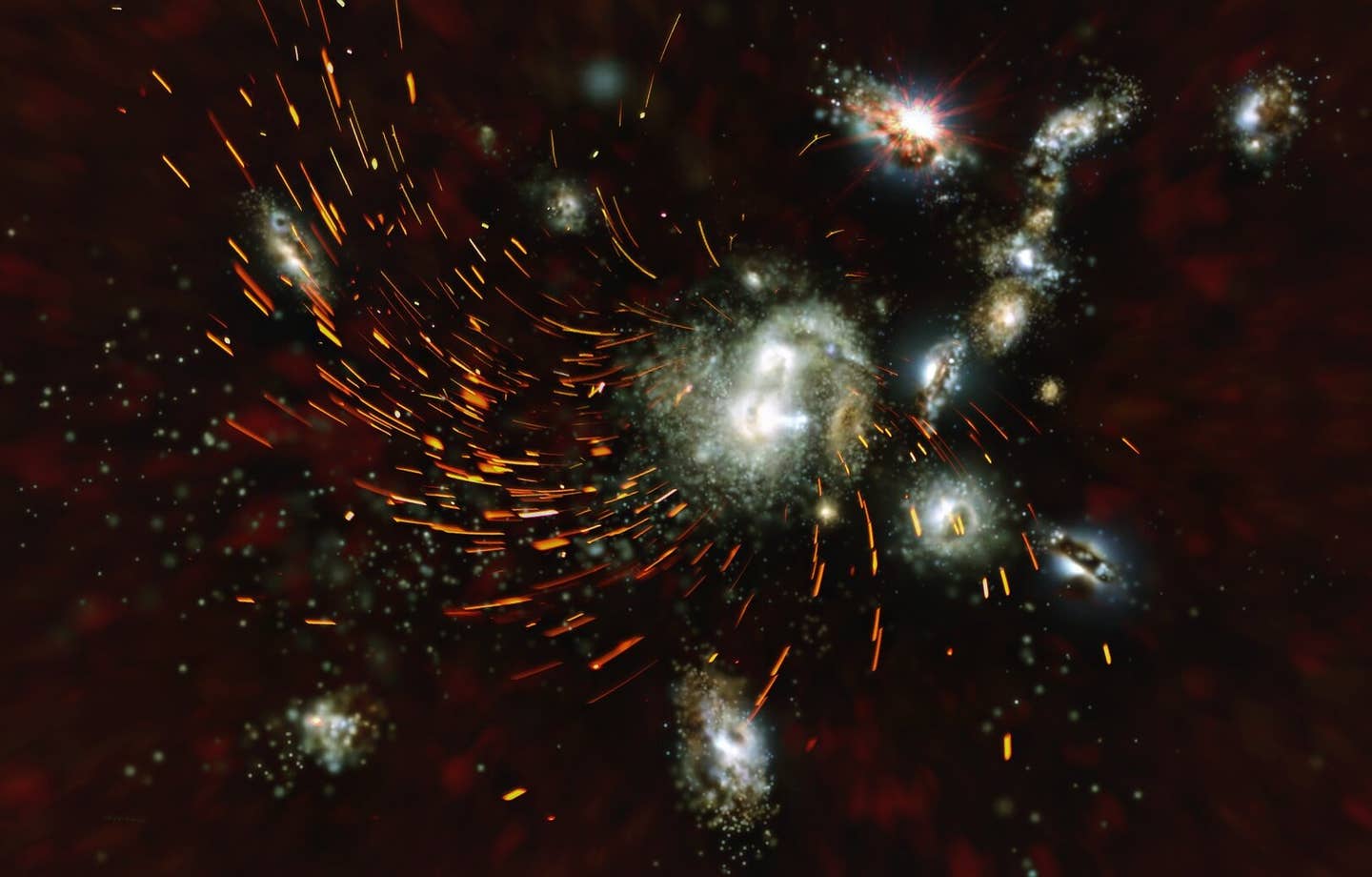

An artist’s rendering of protocluster SPT2349-56 captures clashing galaxies in varied shapes and sizes, with orange gas ripped apart and superheated by tidal forces. (CREDIT: N.Sulzenauer, MPIfR)

Four galaxies crowd the center of a collapsing structure 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang. Each one is churning out stars at a pace that defies comparison with the present-day universe. Around them, long tidal arms sweep outward at 300 kilometers per second, glowing brightly in ionized carbon emission.

Astronomers have puzzled for decades over how massive elliptical galaxies appeared so early in cosmic history. The standard picture suggests large galaxies slowly assembled through repeated mergers over billions of years. Yet observations show mature, gas-poor ellipticals already in place when the universe was still young.

Now, an international team led by Nikolaus Sulzenauer and Axel Weiß of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, has taken a close look at one of the most extreme protoclusters known. Their findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal, offer a rare view of what may be the rapid birth of a giant elliptical galaxy.

A Stellar Factory at Record Speed

The object at the center of the study is SPT2349−56, located in the constellation Phoenix. It sits at redshift z = 4.303, just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang. This system was first identified in the South Pole Telescope SPT-SZ survey and later resolved into multiple components with APEX and ALMA.

SPT2349−56 hosts an extraordinary star formation rate of about 6,700 solar masses per year within 400 kiloparsecs. That is the highest known rate for a group-sized halo of roughly 10¹³ solar masses. For comparison, the Milky Way forms only a few stars per year.

At the core, Sulzenauer and colleagues focused on four tightly interacting galaxies. According to Ryley Hill of the University of British Columbia, these galaxies forge one star every 40 minutes. The Milky Way needs about a year to produce three or four.

The quartet is not quiet. It launches giant tidal arms that extend over regions larger than our galaxy. These arms glow intensely in the [C II] 158 micrometer line of ionized carbon, their brightness enhanced by shock waves that excite the gas.

That bright emission allowed the team to trace gas motions in remarkable detail.

A Beads-on-a-String Collapse

The tidal debris forms what Sulzenauer describes as a gravitationally ejected spiral, resembling beads on a string encircling the protocluster core. Clumps of debris link to a chain of 20 additional colliding galaxies farther out.

Altogether, about 40 gas-rich galaxies populate this core. Most will not survive as separate systems. The team estimates they will merge and transform into a single giant elliptical galaxy within less than 300 million years.

“In a universe where larger galaxies grow hierarchically through gravitational interactions and mergers of smaller building blocks, some giant ellipticals must have formed completely differently than previously thought,” Sulzenauer explains.

Instead of gradually assembling mass over 14 billion years, he suggests that a massive elliptical can emerge within only a few hundred million years. The collapse and coalescence of a primordial overdense structure may do the job in roughly the time it takes the Sun to orbit the Milky Way once.

The researchers find that the densest structures likely decoupled from cosmic expansion when the universe was only about 10 percent of its current age. From there, rapid assembly followed.

For the first time, the team says, astronomers are witnessing the onset of a cascading merging transformation.

Ionized Carbon as a Cosmic Tracer

To study this collapse, the group relied on the [C II] fine-structure line at 1900.537 GHz. This line is a primary cooling channel of the cold interstellar medium and is widely used at redshifts above 2 to estimate molecular gas mass and star formation rates.

The emission mainly arises from photodissociation regions on the surfaces of molecular clouds, though some originates in hot ionized gas. Because of its brightness, it serves as a powerful tracer of cold gas dynamics in dusty star-forming galaxies.

Earlier work by Hill and collaborators had reported a giant [C II] arc near three ultraluminous infrared galaxies in the core of SPT2349−56. Sulzenauer’s team built on that discovery, mapping the arc and surrounding structures in greater detail.

The motion of the gas and the distribution of tidal debris suggest intense gravitational interactions. Shock heating from collisions boosts the [C II] emission by roughly a factor of ten in parts of the system.

That enhancement made it possible to measure gas kinematics across the collapsing core.

Simulations Bridge Past and Present

To connect these observations with the broader history of galaxy clusters, Duncan MacIntyre and Joel Tsuchitori, undergraduate students at the University of British Columbia, ran detailed numerical simulations.

The simulations indicate that such an extreme concentration of submillimeter galaxies is dynamically unstable. The system should collapse rapidly into a single proto–brightest cluster galaxy with a stellar mass near 10¹² solar masses within 100 to 300 million years.

The match between the simulated outcome and mature galaxy clusters seen at later cosmic times is striking. It supports the idea that simultaneous major mergers play a central role in forming the most massive galaxies.

Yet not everything is settled.

Scott Chapman of Dalhousie University notes that many interactions remain poorly understood. “While our findings offer exciting new insights into rapid elliptical galaxy assembly, the various interactions between the merger shocks, gas heating from the growth of supermassive black holes, and their effect on the fuel for star-formation, remain big mysteries,” he says.

Radio observations have detected emission consistent with a radio-loud active galactic nucleus in one of the central galaxies. X-ray data provide further support. Black hole growth may already be influencing the environment.

A Challenge to Formation Models

Brightest cluster galaxies today sit deep in gravitational wells and are embedded in hot, X-ray-bright gas. Their stellar ages suggest that much of their mass formed before redshift 4.

That timing has long challenged models of structure formation. Simulations often struggle to reproduce the observed number of galaxies with stellar masses above 10¹¹ solar masses at such early epochs.

SPT2349−56 occupies this rare regime. Objects of this type have a number density near 10⁻⁵ per cubic comoving megaparsec, where many models underpredict their abundance.

The extreme star formation rate density in this system, about 4 × 10⁴ solar masses per year per cubic megaparsec, exceeds that of any comparable high-redshift group known.

At the same time, only about 55 percent of the submillimeter flux detected by APEX was recovered with ALMA. That shortfall highlights the importance of a multiphase circumgalactic gas reservoir that may feed and regulate the collapse.

Research findings are available online in The Astrophysical Journal.

The original story "How did massive elliptical galaxies appear so early after the Big Bang" is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- Computer models reveal how early black holes grew so quickly after the Big Bang

- Astronomers reveal what happened less than a second after the Big Bang

- What came before the Big Bang? Supercomputers take on Einstein's equations

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.