How NASA turned exoplanets into tourist destinations

A team of designers and scientists at JPL has been producing retro travel posters that reimagine alien planets as if they were your next vacation spot.

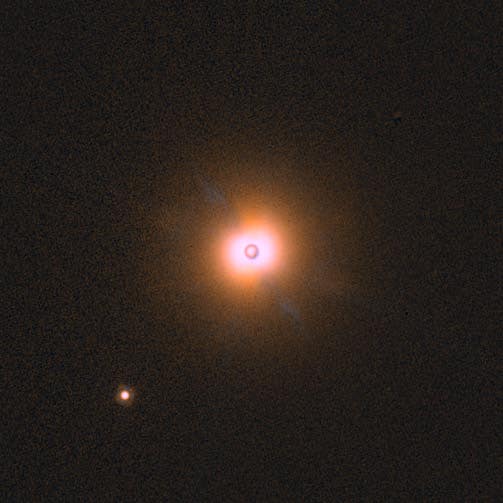

NASA’s Exoplanet Travel Bureau turned abstract data into retro travel posters, blending science and art to make alien worlds feel real. (CREDIT: ESO VLT SPHERE; Van Holstein et al.)

When scientists discovered the first planet orbiting another star in 1995, few outside astronomy circles noticed. That planet, 51 Pegasi b, opened the door to a field that now boasts more than 5,000 confirmed worlds. Yet despite this explosion of discoveries, the public rarely sees more than a faint speck of light in an image or a complicated chart of data. How do you turn something so distant and abstract into a place that feels real?

NASA’s Exoplanet Travel Bureau found a surprising answer: art. Since 2015, a team of designers and scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) has been producing retro travel posters that reimagine alien planets as if they were your next vacation spot.

The posters draw inspiration from 1930s Works Progress Administration designs that once promoted trips to America’s national parks. Instead of Yellowstone or Yosemite, however, these posters advertise Kepler-16b, with its twin suns, or the lonely PSO J318.5−22, where darkness never ends.

The project quickly captured global attention. Millions downloaded the posters for classrooms, office walls, and even film sets. People who had never heard of an exoplanet suddenly had one hanging in their living room.

When Science Meets Imagination

Behind the lighthearted designs lies a serious collaboration between scientists and artists. The travel bureau grew from a recognition that exoplanet research lacks eye-catching visuals. Hubble Space Telescope images of nebulae or Mars rover selfies can stir emotions and spark interest. But most exoplanet discoveries come from careful study of starlight, where the presence of a planet is inferred by tiny dips in brightness. Even rare direct photos of these worlds appear as blurry dots.

Communicator and researcher Ceridwen Dovey explored this challenge in a recent paper in the Journal of Science Communication. She described how the Bureau overcame two major hurdles: the lack of dramatic imagery and the inhospitable conditions of most exoplanets. Many of these distant worlds are far too hot, toxic, or storm-ridden for human visitors. Portraying them as tourist paradises required both creativity and constant dialogue with scientists.

The posters don’t pretend to be photographs. Instead, they walk a careful line between grounded science and bold speculation. A poster for Kepler-186f, for example, shows red-leafed plants, reflecting the fact that its cooler star emits a different color of light. The art doesn’t promise accuracy but builds on real science to suggest what might be possible.

Related Stories

- Astronomers discover a newborn gas-giant exoplanet circling a young 5 million-year-old star

- Exoplanets may capture dark matter and collapse into black holes

Building Worlds Together

Joby Harris, the lead illustrator at JPL, often describes the design process as “dancing with scientists.” One vivid case involved 55 Cancri e, a planet believed to be covered by oceans of lava. Early drafts imagined space trains crossing fiery landscapes. Scientists pushed back, noting that there might not be solid ground at all.

A later sketch pictured boats on molten seas, but that didn’t quite capture the mood. Then a scientist suggested that silicate particles could make the sky glitter. That idea inspired a hot-air balloon drifting over glowing lava, wrapped in a protective bubble. The final poster carried the tagline: “Skies sparkle above a never-ending ocean of lava.”

That back-and-forth happened again and again. Scientists corrected physical details, and artists found fresh ways to represent the worlds. Planetary scientist Morgan Cable recalled sketching ideas live with Harris during a conference. She said artists helped her notice practical design questions—like how spacecraft might touch down on alien ground—that she hadn’t considered. The posters didn’t just communicate science; they also nudged scientists to think differently about their own work.

From Outreach to Inspiration

NASA has a long history of working with artists, dating back to the 1950s when it commissioned paintings of rockets and lunar landscapes. The Exoplanet Travel Bureau followed that tradition but updated it with a style that felt nostalgic and futuristic at once.

When the first set of posters appeared online in 2015, they spread far beyond NASA’s own channels. They showed up at conferences, comic conventions, science festivals, and classrooms worldwide. Gary Blackwood, who managed NASA’s exoplanet program, noted that the posters often became “entry points” for people who might otherwise find the science overwhelming. A travel-style poster can spark curiosity, and curiosity can lead someone to learn about light curves, atmospheres, and orbital mechanics.

The campaign also offered virtual reality tours, bilingual stories, and interactive 360-degree experiences. If visiting an exoplanet in person is impossible—Proxima Centauri b, one of the closest, lies more than four light-years away—virtual exploration can still provide a sense of wonder.

Worlds You’ll Never Visit—But Can Picture

Despite the playful tone, the posters highlight a bittersweet truth: we may never set foot on another planet beyond our solar system. Even with the fastest spacecraft ever built, reaching the nearest star system would take tens of thousands of years.

Astrophysicist Joshua Winn has written that humans may never breathe the air of another world. But that hasn’t stopped scientists from trying to understand them. Telescopes such as Kepler and TESS revealed thousands of planets, while the James Webb Space Telescope now studies their atmospheres, searching for water, carbon dioxide, and perhaps signs of life.

Without rich images, the science risks feeling distant and cold. The posters fill that gap, turning points of light into places you can imagine standing on, if only for a moment. They embrace their speculative nature while remaining tied to research. That balance gives them power—inviting you to dream while still grounding the vision in data.

How Art Shapes Science

The collaboration behind the Exoplanet Travel Bureau reflects a broader trend in science communication. Scholars like Janet Vertesi and Lisa Messeri have written about “worlding,” the process of turning data into lived, imagined places. Dovey’s study showed that artists are not simply decorative add-ons at the end of a research project. Instead, they can help shape thinking from the start.

Australian poet Alicia Sometimes once asked whether art can inspire science as much as science inspires art. The Bureau seems to answer yes. Harris and his team gave scientists new ways to visualize their own ideas. In turn, scientists gave the artists a framework to imagine worlds no one has seen.

The posters occupy a space between fantasy and realism. They don’t try to trick anyone into thinking they are photographs. Instead, they admit their creative origins, making it easier for scientists to embrace them without fear of misleading the public. That openness, researchers argue, makes both sides more willing to experiment.

A Playful Invitation

Look closely at the posters, and you’ll see taglines that sell the fantasy: “Where your shadow always has company,” or “Nightlife never ends.” The humor is deliberate. It transforms dangerous, inhospitable worlds into destinations you can daydream about.

Dovey points out that this creative leap mirrors what scientists themselves must do. Turning streams of data into a mental picture of a real planet requires imagination. In that sense, the public isn’t doing anything different when they picture standing under twin suns or floating above a lava sea.

The posters remind us that art and science are not distant cousins but close partners. Both rely on curiosity, creativity, and the drive to make the unseen visible.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.