Is asteroid mining actually feasible? Meteorite chemistry data offers new insight

Meteorite chemistry shows which primitive asteroids may hold usable metals or water, and why most space mining remains difficult.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

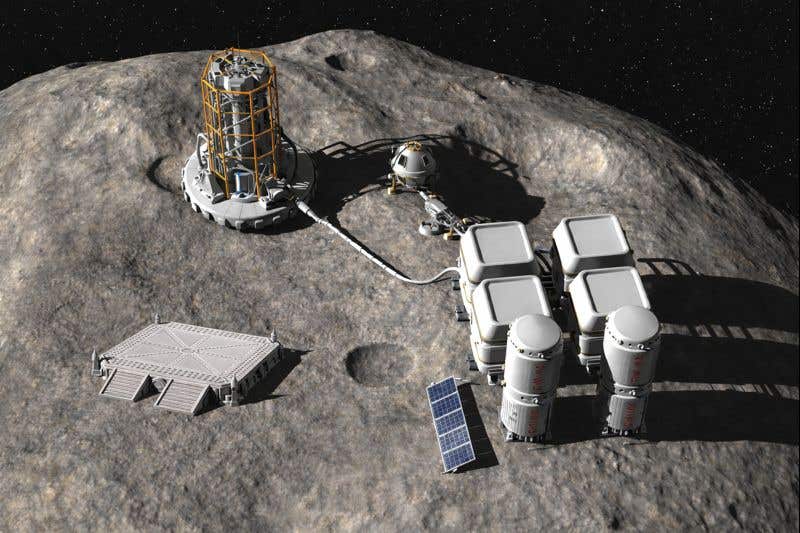

Meteorite chemistry shows which primitive asteroids may hold usable metals or water, and why most space mining remains difficult. (CREDIT: AI-generated image / The Brighter Side of News)

Space mining often sounds like a fast route to endless metals. In practice, the first question is simple: what are small asteroids actually made of, in measurable detail?

Researchers at the Institute of Space Sciences, part of the Spanish National Research Council, known as ICE-CSIC, tackled that question by studying carbon-rich meteorites that serve as stand-ins for C-type asteroids. The work was led by astrophysicist Josep M. Trigo-Rodríguez of ICE-CSIC, affiliated with the Institute of Space Studies of Catalonia, known as IEEC. The chemical analyses were carried out at the University of Castilla-La Mancha by Professor Jacinto Alonso-Azcárate, using mass spectrometry to map the elemental makeup of key meteorite groups. Jordi Ibáñez-Insa, a researcher at Geosciences Barcelona, known as GEO3BCN-CSIC, also contributed as a co-author.

Their findings, published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, use real meteorite chemistry to test which asteroid-mining claims hold up, and which do not.

These samples come from carbonaceous chondrites, fragile meteorites linked to primitive, undifferentiated asteroids. Only a small fraction of meteorite falls belong to this carbon-rich category. Many break apart in the atmosphere and never reach collectors, which is why deserts like the Sahara and Antarctica become key hunting grounds.

“The scientific interest in each of these meteorites is that they sample small, undifferentiated asteroids, and provide valuable information on the chemical composition and evolutionary history of the bodies from which they originate,” Trigo-Rodríguez said.

What “undifferentiated” really means for resources

Many commercial road maps focus on metal-rich, differentiated asteroids. Those bodies once melted, sorted into layers, and formed dense metal cores. If you can reach a core fragment, the thinking goes, you can harvest iron-nickel alloys and the elements that travel with them.

This study points you toward a different target class. Undifferentiated asteroids never fully melted. They kept a more mixed, early-solar-system recipe, with metals, rock-forming minerals, and in some cases, water-bearing materials. That makes them scientifically valuable, and potentially useful for selected resources.

But “primitive” does not mean “simple.” Over billions of years, impacts churn asteroid surfaces into regolith and breccias, turning loose grains into tough, mixed material. That history complicates any plan that assumes you can scoop, sift, and cleanly separate metal from rock.

“Although most small asteroids have surfaces covered in fragmented material called regolith -and it would facilitate the return of small amounts of samples-, developing large-scale collection systems to achieve clear benefits is a very different matter,” said Pau Grèbol Tomás, an ICE-CSIC predoctoral researcher.

Ibáñez-Insa added that the environmental motivation matters, even if the engineering remains hard. “In any case, it deserves to be explored because the search for resources in space could be susceptible to minimizing the impact of mining activities on terrestrial ecosystems,” he said.

How the team tested mining claims with laboratory chemistry

To move past speculation, the team measured bulk chemistry in six major carbonaceous chondrite families: CI, CO, CM, CK, CV and CR. The samples mostly came from NASA’s Antarctic meteorite collection, held in part through international curation networks that researchers can request access to for clean analyses. Orgueil, a well-known recovered fall, served as a check against weathering effects seen in some Antarctic finds.

At ICE-CSIC, the researchers selected and characterized specimens in controlled conditions, then sent them for chemical measurement. “At ICE-CSIC and IEEC, we specialize in developing experiments to better understand the properties of these asteroids and how the physical processes that occur in space affect their nature and mineralogy,” Trigo-Rodríguez said.

He also framed the paper as a long build. "The work now being published is the culmination of that team effort," he added.

In the lab, major elements and trace elements were measured with ICP-based techniques that can capture dozens of elements, from common rock formers to rare earth elements. The team reports successful measurement of 46 elements, spanning sodium through uranium, while noting that a few elements could not be measured because of method limits.

Which elements look promising, and which do not

"When our research team compared the carbonaceous chondrite groups, several patterns emerged. Some transition metals, such as titanium, appeared consistently enriched relative to CI baselines. Other elements, including copper and especially zinc, showed depletion in many groups," Ibáñez-Insa shared with The Brighter Side of News.

"That matters because mining only makes sense when concentration, collection, and processing line up. On Earth, many profitable mines exist because geology concentrates elements far above average crust levels. Bulk asteroid material often does not offer that same kind of natural concentration," he continued.

The rare earth results carry the same lesson. Some carbonaceous chondrite groups, especially CV, CK and CO, showed higher rare earth abundances than CI within the study’s dataset. Yet the paper argues that Earth’s upper crust, and especially terrestrial deposits, often still outcompete these meteorites on concentration by a wide margin. You can treat that as a warning against simplistic “rare earth asteroid” headlines.

The study also stresses a practical distinction that shapes target choice. If an asteroid experienced significant water-driven alteration, metals may oxidize and become less attractive for extraction. If an asteroid stayed relatively “dry,” native metals may remain in more useful forms. That tradeoff becomes central when you think about whether your mission aims for metals or water.

The best targets may be narrow, and mission planning matters

The team’s conclusion is not that asteroid mining is ready. It is that some targets look more sensible than others, and you need better “ground truth” to pick them.

One path involves linking meteorites to specific asteroid classes using remote spectral taxonomies. The study flags K-class asteroids, often associated with CO and CV-like material, because their reflectance spectra can show olivine and spinel absorption bands. Those signals may help identify more pristine parent bodies.

At the same time, the authors underline that sample-return missions remain essential. Small returned samples from missions such as Hayabusa2 and OSIRIS-REx have already reshaped how scientists link specific asteroids to carbonaceous meteorites. Those missions also show that a single asteroid can be chemically varied from place to place.

Trigo-Rodríguez said major progress will require industry-level engineering, not just scientific interest. “Alongside the progress represented by sample return missions, companies capable of taking decisive steps in the technological development necessary to extract and collect these materials under low-gravity conditions are truly needed,” he said. “The processing of these materials and the waste generated would also have a significant impact that should be quantified and properly mitigated.”

Grèbol Tomás framed the moment as familiar, even if it still sounds futuristic. “It sounds like science fiction, but it also seemed like science fiction when the first sample return missions were being planned thirty years ago,” he said.

Practical Implications of the Research

This work pushes asteroid mining discussions toward measurable chemistry and away from slogans. In the near term, that can help mission planners choose targets that match a specific goal, such as water extraction for propulsion or life support, or limited recovery of selected metals for in-space manufacturing. It also helps researchers prioritize which asteroid families deserve new sample-return missions, since returned material remains the strongest check on remote sensing.

For humanity, the biggest benefit may come from treating space resources as infrastructure for exploration, not as a replacement for Earth mining. If future missions can extract water from water-altered asteroids, that resource could reduce dependence on launches from Earth and support longer stays on the Moon or Mars. The research also sharpens planetary defense discussions by improving how you identify and characterize small bodies that pass near Earth. Better composition data can support better models of how an object behaves, and how you might respond.

At the same time, the study sets expectations. It suggests you should view most primitive asteroids as chemically interesting but economically challenging, unless technology changes the cost of collection, separation and processing under low gravity.

Research findings are available online in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Related Stories

- Asteroid Bennu samples reveal ancient water offering new clues about the origin of life on Earth

- 12-year-old Canadian discovers two new asteroids in NASA program

- Astronomers weigh nuclear option to stop Moon-bound asteroid

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer