JWST solves a longstanding mystery of giant planet formation

New James Webb observations of the HR 8799 system reveal that even massive gas giants can form through core accretion, much like Jupiter.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

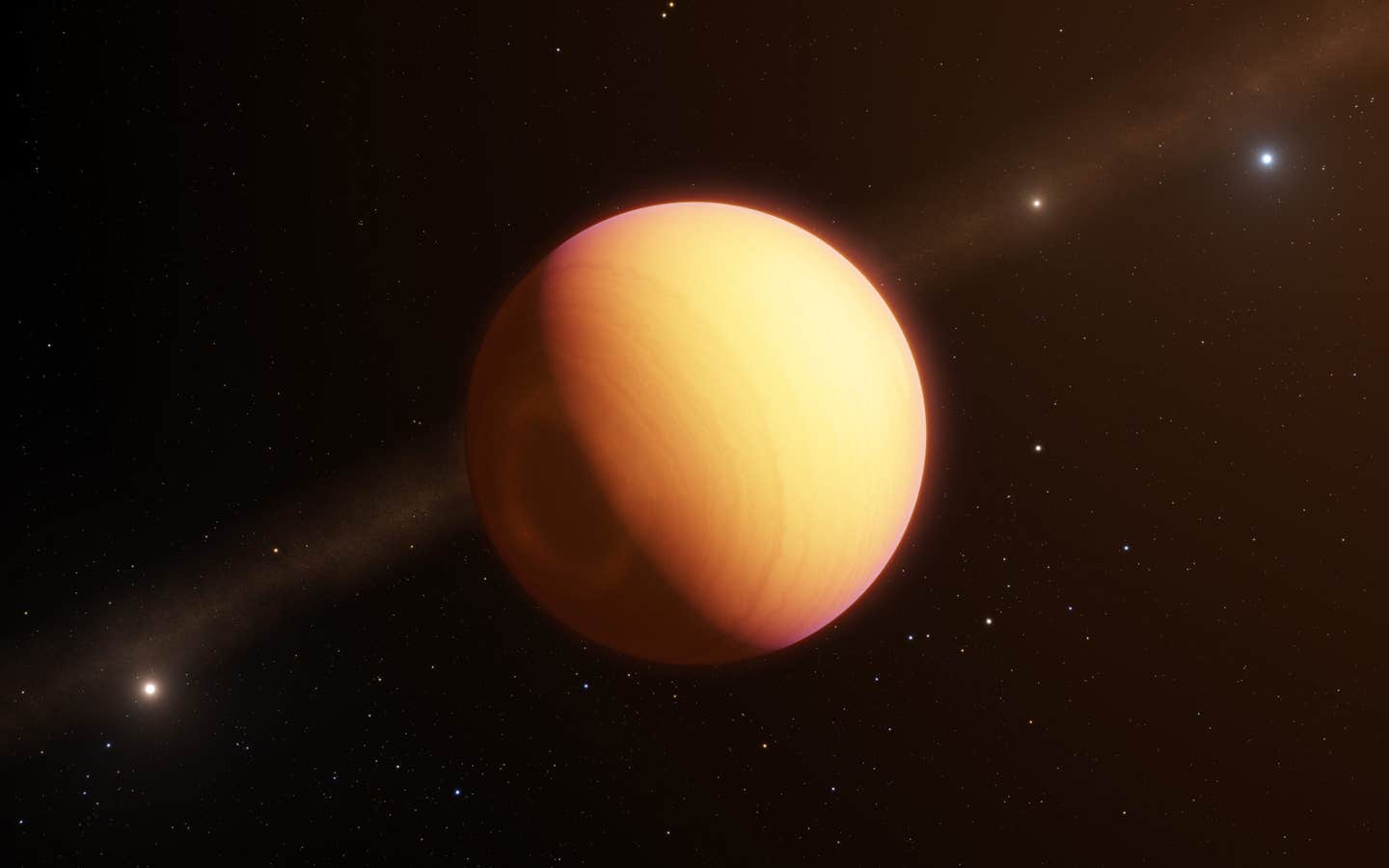

This artist’s impression shows the observed exoplanet, which goes by the name HR8799e. (CREDIT: ESO/L. Calçada/SpaceEngine)

Gas giants are massive worlds made mostly of hydrogen and helium. They lack solid surfaces, and in our solar system, Jupiter and Saturn are the best-known examples. Beyond our cosmic neighborhood, astronomers have found gas giants that dwarf Jupiter, blurring the line between planets and brown dwarfs, sometimes called failed stars. How these enormous planets form has been a long-running puzzle in astronomy.

Now, new research led by scientists at the University of California San Diego is offering a clearer answer. Using fresh data from the James Webb Space Telescope, the team studied a distant planetary system called HR 8799. Their findings, published in the journal Nature Astronomy, suggest that even the biggest gas giants can form in ways similar to Jupiter and Saturn, despite their extreme size.

The work was led by Jean-Baptiste Ruffio, a research scientist at UC San Diego, alongside Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics Quinn Konopacky. Jerry Xuan, a 51 Pegasi b Fellow at UCLA, played a key role by building detailed atmospheric models that helped decode the telescope data.

A Strange Solar System Look-Alike

The HR 8799 system sits about 133 light-years away in the constellation Pegasus. It has four known gas giants, each five to ten times heavier than Jupiter. These planets orbit far from their star, between 15 and 70 times the Earth’s distance from the sun. That spacing makes the system a scaled-up version of our own, which also has four outer giants stretching from Jupiter to Neptune.

Because these planets are so large and so far from their star, many scientists doubted they could have formed through core accretion. That process, which shaped Jupiter and Saturn, starts with small rocky and icy pieces clumping together. Over time, those cores grow heavy enough to pull in surrounding gas. Far from a star, this growth usually takes too long.

That doubt pushed astronomers to consider another idea, called gravitational instability. In that scenario, parts of the gas disk around a young star collapse quickly into giant objects. This method is more like how stars form and can create massive bodies fast.

Webb’s Sharp New Eyes

To test these ideas, researchers turned to the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST. The telescope’s powerful spectrograph can split light into fine detail, revealing which molecules are present in a planet’s atmosphere. Because HR 8799 is only about 30 million years old, its planets are still warm and bright, making them easier to study.

Earlier studies relied on ground-based telescopes and focused on molecules like water and carbon monoxide. Scientists later realized those gases can be misleading because they can come from both gas and solid material. Instead, the team searched for sulfur, a heavier element that stays locked in solids during planet formation.

“With its unprecedented sensitivity, JWST is enabling the most detailed study of the atmospheres of these planets, giving us clues to their formation pathways,” Ruffio said. “With the detection of sulfur, we are able to infer that the HR 8799 planets likely formed in a similar way to Jupiter despite being five to ten times more massive, which was unexpected.”

Pulling a Signal From the Noise

Finding sulfur was not easy. The planets are about 10,000 times fainter than their host star, and JWST was not built specifically for this task. Ruffio developed new ways to process the data and tease out the faint planetary signals.

“The quality of the JWST data is truly revolutionary and existing atmospheric model grids were simply not adequate,” Xuan said. “To fully capture what the data were telling us, I iteratively refined the chemistry and physics in the models. In the end, we detected several molecules in these planets, some for the first time, including hydrogen sulfide.”

The clearest sulfur signal came from HR 8799 c, the third planet in the system. The team believes sulfur is likely present in the other inner planets as well. Alongside sulfur, the planets showed higher levels of heavy elements like carbon and oxygen compared with their star.

Rethinking Old Models

Those chemical fingerprints point strongly toward core accretion. Gravitational instability would produce planets with compositions close to their star. Instead, these planets appear enriched by solid material.

“There are many models of planet formation to consider,” Konopacky said. “I think this shows that older core accretion models are outdated. And of the newer models, we are looking at ones where gas giants can form solid cores really far away from their star.”

The findings also raise new questions. Ruffio wonders how massive a planet can become while still forming like a planet.

“I think the question is, how big can a planet be?” he said. “Can a planet be 15, 20, 30 times the mass of Jupiter and still have formed like a planet? Where is the transition between planet formation and brown dwarf formation?”

For now, HR 8799 stands as a rare case. It is still the only known system with four directly imaged giant planets, though other systems with one or two massive companions are known.

Practical Implications of the Research

This study reshapes how scientists think about planet formation across the galaxy. It shows that core accretion can work under more extreme conditions than once believed, even far from a star. That insight will help astronomers refine models of how planetary systems grow and evolve.

The research also highlights JWST’s power to read the chemical history written in alien skies. As the telescope studies more worlds, scientists expect to uncover whether Jupiter-like formation is common or rare.

In the long run, understanding how giant planets form helps explain the architecture of planetary systems, including those that may host Earth-like worlds.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The original story "JWST solves a longstanding mystery of giant planet formation" is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- Sun-like star’s nine-month eclipse exposes a violent planetary past

- Deep magma oceans generate magnetic fields to protect planets and support life

- Gravitational lensing helps astronomers determine the true mass of a rogue planet

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.