Mass extinction helped jawed vertebrates rise, study finds

A Science Advances study links the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction to the later rise and diversification of jawed vertebrates.

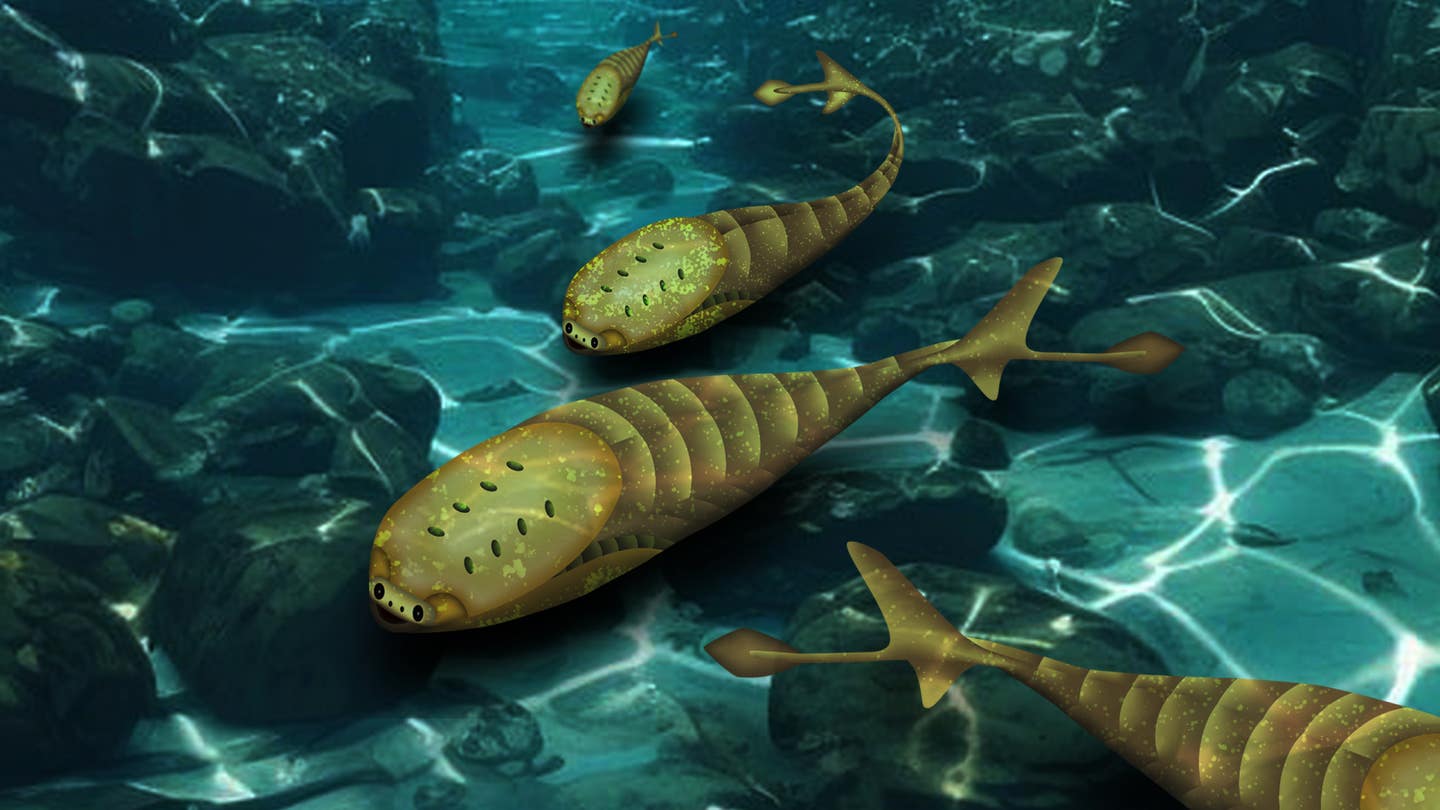

After an ancient extinction killed about 85% of marine species, survivors in isolated refuges helped jawed vertebrates diversify and later dominate. (CREDIT: Kaori Serakaki (OIST))

About 445 million years ago, Earth’s oceans turned into a danger zone. Glaciers spread across the supercontinent Gondwana, and shallow seas shrank fast. Ocean chemistry also shifted hard. In what scientists call the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction, about 85% of marine species died. Most life on Earth lived in the sea then.

A new study argues that this disaster also lit a fuse. Researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology say the extinction helped set jawed vertebrates on their path to dominance. That group includes jawed fishes, and it later includes every vertebrate line you know today.

“We have demonstrated that jawed fishes only became dominant because this event happened,” said senior author Professor Lauren Sallan of the Macroevolution Unit at OIST. She said the team connected the fossil record to ecology and geography in a new way.

The study also pulls the camera back on a confusing chapter in evolution. Vertebrates existed before this extinction. Yet the fossil record shows many major vertebrate groups appearing later. The new work suggests that delay was not just chance. It reflected real ecological bottlenecks and then a long, powerful rebound.

A World of Warm Seas, Then a Sudden Freeze

During the Ordovician Period, from about 486 to 443 million years ago, the planet looked unfamiliar. Gondwana dominated the south. Vast, shallow seas covered huge areas. The poles had no ice. Warm water spread widely under a greenhouse climate.

Life in those seas looked strange by modern standards. Conodonts, described as large-eyed and lamprey-like, moved through the water. Trilobites crawled along the seafloor. Mollusks formed dense swarms. Giant nautiloids with pointed shells stretched up to five meters. Sea scorpions reached human size.

In that busy world, the ancestors of jawed vertebrates were rare. They did not rule the seas. They lived among many other successful animals.

Then came a sharp before-and-after line. “While we don’t know the ultimate causes of LOME, we do know that there was a clear before and after the event. The fossil record shows it,” Sallan said.

The extinction came in two pulses, the researchers said. First, Earth flipped from greenhouse to icehouse conditions. Glaciers covered much of Gondwana. Many shallow habitats dried out. A few million years later, as life started to recover, the climate flipped again. Ice melted. Warmer water returned, but it came with harsh chemistry. The researchers describe it as warm, sulfuric, and low in oxygen.

Survivors Huddled in Refugia, Then Life Rebuilt

"As the oceans changed, survivors did not spread evenly. Many ended up in refugia. These were isolated hotspots where life could persist. Deep ocean stretches separated them, and those waters acted like barriers," Sallan explained to The Brighter Side of News.

"In these refugia, the study suggests, surviving jawed vertebrates had an edge. They faced ecosystems full of open roles. Many competitors, including jawless vertebrates and other animals, had died," she continued.

First author Wahei Hagiwara said the team rebuilt the story using an unusually broad fossil record effort. “We pulled together 200 years of late Ordovician and early Silurian paleontology,” he said. Hagiwara worked as a research intern at OIST and is now a PhD student there.

The team created a new database from fossils across the world. With it, they reconstructed refugia ecosystems and measured genus-level diversity. Their analysis shows a clear trend. After the extinction pulses, jawed vertebrates increased in diversity over several million years. The pattern was gradual, but dramatic.

“And the trend is clear; the mass extinction pulses led directly to increased speciation after several millions of years,” Hagiwara said.

This is not a story of instant takeover. It is a story of pressure, isolation, and time. In refugia, small populations could diversify. They could also explore empty ecological space without the same level of competition.

Tracing a Global Shuffle After a Global Shock

The study also focuses on where these survivors lived and how they moved. Sallan said the team could track species movement across the globe. “This is the first time that we’ve been able to quantitatively examine the biogeography before and after a mass extinction event,” she said.

That geographic lens matters because it helps explain why jaws became so important. The researchers argue that jawed vertebrates did not evolve jaws simply to invent a new lifestyle. Instead, they likely stepped into existing roles first. Then they diversified further.

“Did jaws evolve in order to create a new ecological niche, or did our ancestors fill an existing niche first, and then diversify?” Sallan asked. “Our study points to the latter.”

The team points to a striking example in what is now South China. There, they see the first full-body fossils of jawed fishes linked directly to modern sharks. Those fishes stayed concentrated in stable refugia for millions of years. Later, they evolved the ability to cross open ocean and expand into other ecosystems.

The study compares that process to a more familiar case. Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos Islands diversified their diets to survive. Over time, their beaks shifted to match those roles. In the new study, early jawed vertebrates appear to have followed a similar logic. They found opportunity first. Morphology followed with time.

Jawless relatives did not vanish right away. The study says they continued evolving elsewhere and dominated wider seas for the next 40 million years. Some developed alternative mouth structures. That parallel story underscores a key point. Jawed vertebrates did not win immediately. Their later dominance still holds a mystery.

A “Diversity-Reset Cycle” That Keeps Returning

The researchers describe the extinction as an ecological reset, not a total wipeout. Ecosystems rebuilt, but with different players. Early vertebrates stepped into roles left open by conodonts and arthropods. Over time, the overall structure of ecosystems returned, even as the species changed.

The team calls this a recurring “diversity-reset cycle.” After similar environmental shocks in the Paleozoic, evolution often rebuilt ecosystems toward familiar functional designs. The species lists changed, but the jobs in the ecosystem filled again.

Sallan says this integrated view helps answer big questions. It helps explain why jaws evolved, why jawed vertebrates later prevailed, and why modern marine life traces back to these survivors. It also shows how long-term patterns can hide in plain sight. You only see them when you combine location, ecology, morphology, and diversity.

The result is a more personal view of deep time. Earth’s worst moments can shape what comes next. The path to today’s vertebrate world ran through an ancient crisis, and it ran through the small refuges where survivors endured.

Practical Implications of The Research

This study gives researchers a clearer way to connect extinction events to later evolutionary success. It links fossils with ecology and geography to explain cause and effect.

The work highlights refugia as engines of recovery and innovation. Future studies can look for similar hotspots after other mass extinctions.

The “diversity-reset cycle” idea offers a framework for testing repeated patterns in the Paleozoic. Researchers can ask if ecosystems rebuild toward similar functional designs after similar shocks.

By clarifying how jawed vertebrates rose, the study helps explain why modern vertebrate life traces back to particular survivors. That context can guide new fossil searches and new databases.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

Related Stories

- Severe drought pushed the ‘hobbits’ of Flores toward extinction 61,000 years ago

- New fossil discoveries reveal life before Earth’s greatest extinction

- What drove North America’s large mammals to extinction after the last ice age

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Hannah Shavit-Weiner

Medical & Health Writer

Hannah Shavit-Weiner is a Los Angeles–based medical and health journalist for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication focused on uplifting, transformative stories from around the globe. Passionate about spotlighting groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, Hannah covers a broad spectrum of topics—from medical breakthroughs and health information to animal science. With a talent for making complex science clear and compelling, she connects readers to the advancements shaping a brighter, more hopeful future.