Melting Antarctic ice could cripple a deep ocean climate engine

New modeling shows melting ice shelves and weaker sea ice near Cape Darnley can slow deep Antarctic waters that help stabilize global climate.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

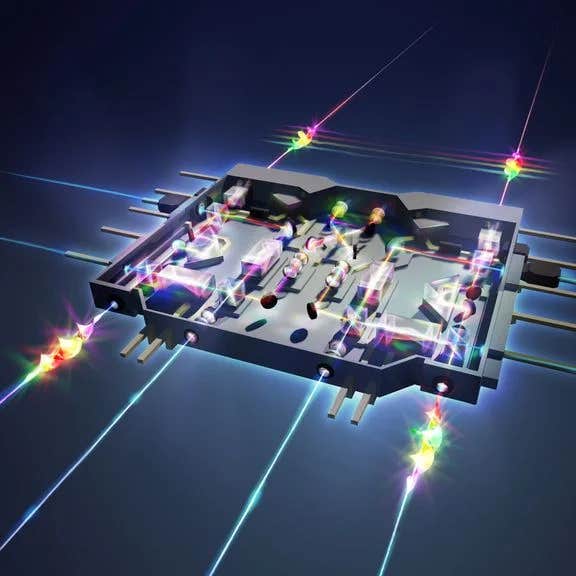

A new study from Australian scientists reveals that melting Antarctic ice shelves and shifting sea ice near Cape Darnley can sharply cut the production of Antarctic Bottom Water, the dense deep ocean flow that helps drive global currents. Even modest changes in this remote region could weaken a key climate “conveyor belt,” with knock on effects for rainfall, heat and weather patterns across the world. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

Cracking, creaking ice at the bottom of the world is quietly shaping the future climate you live in. New research from Australian scientists shows that melting Antarctic ice shelves and changing sea ice are disturbing one of the planet’s most important deep ocean engines, with potential ripple effects for rainfall, heat waves and storms far from the poles.

A team led by Dr David Gwyther at The University of Queensland has pinpointed competing forces around East Antarctica that control the birth of some of the coldest and densest water on Earth. This icy water mass, called Antarctic Bottom Water, helps drive global ocean circulation, like a hidden conveyor belt running along the sea floor. When that conveyor slows, the entire climate system can shift.

“This very cold, salty water, called Antarctic Bottom Water, is formed by the freezing of the ocean surface in sea ice factories that we call polynyas,” Dr Gwyther said.

How the Deep Ocean Conveyor Works

In winter, fierce coastal winds push sea ice away from Antarctica’s shores and open up dark patches of water called polynyas. These areas act like industrial freezers. As the exposed ocean surface refreezes, salt is left behind in the water below, which makes it heavier.

That heavy, briny water sinks to the ocean floor and then spreads northward along the bottom of the global ocean. It acts like a slow moving conveyor belt that helps drive currents around the world and redistributes heat and carbon. This deep circulation shapes climate patterns, from African rainfall to European temperatures.

“Our study shows the formation of bottom water is a fine balance between strong coastal winds, sea ice growth and the volume of fresh water released by melting ice shelves,” Dr Gwyther told The Brighter Side of News. When that balance changes, the amount of dense water that forms can rise or fall.

Cape Darnley, a Small Corner With Big Influence

Antarctic Bottom Water forms in only four known places around the continent. The new work focuses on one of them, near Cape Darnley in East Antarctica, roughly 3,000 kilometers from the Australian mainland. This region had long been a blind spot for scientists trying to understand how deep waters form.

“Until now we haven’t had a clear picture of what controls Antarctic Bottom Water formation at Cape Darnley,” Dr Gwyther said. To change that, the team built an advanced regional ocean model. The simulation combined data on salinity, temperature, currents, sea ice and winds to recreate how water moves and transforms along this remote coast.

The model revealed two neighboring systems that tug the deep ocean engine in opposite directions. Meltwater flowing from beneath the Amery Ice Shelf travels north toward Cape Darnley and makes the coastal water fresher. Fresher water is lighter, so it is less likely to sink and become dense bottom water.

When Ice Shelves Melt and Sea Ice Falters

Just west of Cape Darnley sits the Mackenzie Polynya, a key “sea ice factory” between the Amery Ice Shelf and open water. Strong winds there drive intense sea ice production, which increases salinity in the surface ocean. That extra salt makes the water heavier and strengthens dense water formation.

“Meltwater flowing from beneath the Amery Ice Shelf freshens the water flowing northwards to Cape Darnley and suppresses dense water formation,” Dr Gwyther said. “Conversely, sea ice production in the nearby Mackenzie Polynya region between the Amery Ice Shelf and Cape Darnley increases salinity and strengthens dense water formation. These two systems influence Cape Darnley’s dense water formation in opposite directions.”

The team then tested what happens when that delicate tug of war shifts. In one scenario, they doubled the amount of meltwater coming from under the Amery Ice Shelf. Dense water export from Cape Darnley dropped by about 7 percent. That is a modest change, but it shows how extra melting can quietly weaken the deep conveyor.

In a more extreme test, the researchers shut down sea ice production in the Mackenzie Polynya. Without that powerful salt pump, dense water export plunged by around 36 percent. That result shows how much the global ocean depends on a few wind swept, ice choked patches of Antarctic sea.

Why Changes Near Antarctica Reach Your Weather

It can be hard to connect a faraway polynya to the weather outside your window. Yet the chain is direct. When less dense water forms and sinks around Antarctica, the deep branch of the global circulation slows. That affects how much heat the ocean can store and how quickly it releases that heat back to the atmosphere.

“This is important, as changes to dense water production might over time impact global ocean circulation and affect climate patterns such as rainfall in Africa or temperatures in Europe,” Dr Gwyther said.

If ice shelves melt faster in a warming world, or if coastal winds and sea ice growth shift, the balance around Cape Darnley could tip. Over decades, that change might alter storm tracks, drought patterns and marine ecosystems that many communities depend on. The new study warns that melting ice shelves and shifting sea ice in Antarctica do not stay “down there” in any meaningful sense. They feed into deep processes that help set the climate your children and grandchildren will live in.

For now, the system still works. Dense water continues to form and slide into the abyss. But the research makes clear that this engine is not indestructible. It runs on a knife edge set by winds, salt, and the slow drip of meltwater from beneath the continent’s vast shelves of ice.

Practical Implications of the Research

These findings give climate scientists a sharper picture of how and where deep ocean waters form, which can improve global climate and ocean models. Better models help you get more accurate long range forecasts of sea level rise, marine heat waves and shifting rainfall.

For policymakers, the work underlines why protecting Antarctica’s ice is not just about saving distant glaciers. Steps that limit global warming also reduce ice shelf melt and help preserve the deep circulation that stabilizes climate patterns worldwide.

For communities, especially those in regions already vulnerable to shifting rainfall or changing ocean temperatures, this research reinforces that choices made today about emissions and ice monitoring will influence future weather risks. Understanding the Cape Darnley system helps scientists spot early warning signs if the deep conveyor begins to slow.

If that slowdown happens, the impacts will not be confined to the Southern Ocean. They will show up in altered storm tracks, stressed fisheries and new extremes in heat and rainfall. This study offers both a warning and a tool: a clearer view of one small but vital gear in the planet’s climate machine.

Research findings are available online in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Related Stories

- Scientists find trapped heat beneath Greenland — impacting ice sheet motion and future sea level rise

- Ocean storms under Antarctic ice found to rapidly boost melting

- Melting polar ice supercharges ocean ‘stirring’, threatening marine climate

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.