MIT engineers give biohybrid robots a power upgrade with synthetic tendons

Engineers build artificial tendons that let muscle-powered robots move faster and pull harder, marking a major step for biohybrid machines.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

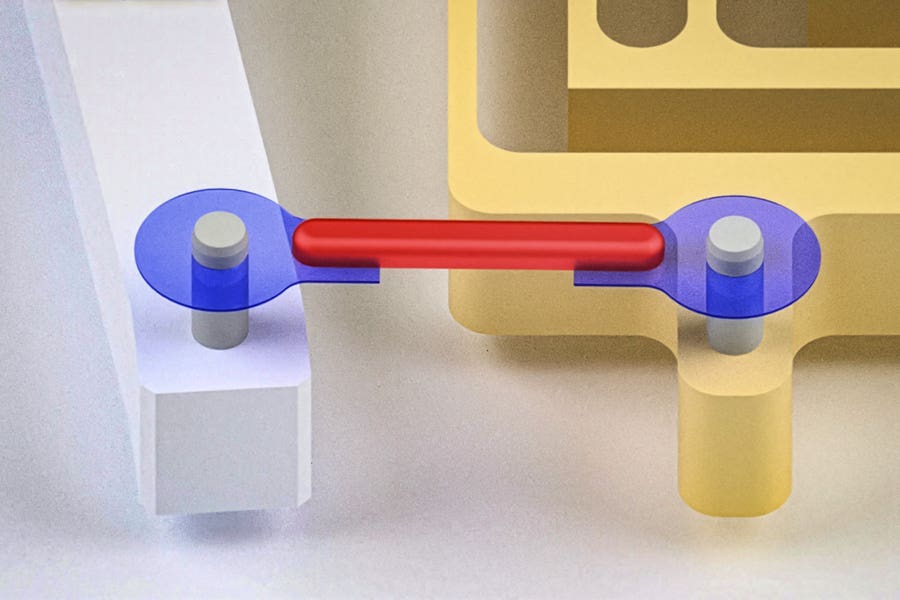

Researchers have developed artificial tendons for muscle-powered robots. They attached the rubber band-like tendons (blue) to either end of a small piece of lab-grown muscle (red), forming a “muscle-tendon unit.” (CREDIT: Ritu Raman et al)

Biohybrid robots that run on real muscle are shifting from science fiction toward workable machines. In labs around the world, engineers have built tiny walkers, swimmers and gripping devices powered by living tissue. These systems can adapt, repair small injuries and move with lifelike smoothness. Yet one stubborn problem has kept them from doing serious work: soft muscle does not connect well to stiff plastic or metal. The mismatch wastes energy and often damages tissue.

A new study shows a solution borrowed straight from biology. In your body, muscles never clamp directly onto bone. They connect through tendons, which form a muscle–tendon unit that transfers force efficiently and reduces damage. By copying this system in the lab, researchers have built a stronger and more efficient way to link living muscle to robotic structures.

The work, published in the journal Advanced Science, comes from engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and collaborators. They designed artificial tendons from hydrogel and used them to connect strips of lab grown muscle to a mechanical gripper. The result was a device that moved faster and pulled with far more force than earlier designs.

In tests, the gripper pinched about three times faster and delivered roughly 30 times more force than similar robots without tendons. It also survived more than 7,000 movement cycles without the connections failing. Those are major steps for a field that has long struggled with weak links between biology and engineering.

Copying the body’s design

In vertebrates, tendons form a smooth bridge from soft muscle to rigid bone. Muscle tissue is flexible and contracts easily, while bone resists motion with great strength. Tendons sit in between, both in stiffness and function. They absorb shock, guide movement and allow bulky muscles to control distant joints through thin, cable-like links.

The MIT team recreated this setup by making a small muscle–tendon unit in the lab. Each unit consisted of a narrow strip of engineered skeletal muscle with a synthetic tendon attached at each end. These units could then be fitted onto different robot frames much like a standard part.

The muscle strips were grown from mouse cells commonly used in laboratory studies. Over about two weeks, the cells fused into fibers that could contract when stimulated by blue light. This let the team control each unit without touching it, a useful feature for tiny machines.

For the tendons, the group turned to hydrogel, a rubbery material that can be tough or soft depending on its mix. The version used here combined two polymers that form a strong network when bonded together. The gel was also treated with a chemical that lets it form a tight bond with biological tissue.

Each tendon was attached to the end of a muscle strip with a tiny overlap, just one millimeter wide. Even at that small size, the bond handled far more force than the muscle could produce, which meant the joint did not fail during testing.

Tests also showed the tendon material did not harm the living cells. Muscles grown with the gel stayed as healthy as those grown alone, an important check for any device that relies on living tissue.

From model to machine

Before building the full robot, the researchers created a simple model to predict how the muscle, tendon and skeleton would interact. They treated the system like three springs connected in a line, each with its own stiffness. This helped them calculate how firm the tendons should be to move a mechanical joint without wasting force.

From the model, they learned the artificial tendons needed to be much stiffer than the muscle. Once the gel was mixed to that level, the motion of the real setup closely matched what the math had predicted.

They also tested how much the muscle should be stretched before use. Units that were slightly taut performed best. When the tissue was overstretched, performance did not improve and risk increased. At the right tension, the muscle moved the skeleton with the greatest efficiency.

Speed tests showed another benefit of the tendon design. Muscles mounted directly on frames lost motion at higher rates of stimulation. Those linked by tendons kept moving well even when activated four times per second. At still higher rates, the muscles held steady contractions, showing potential for continuous force when needed.

Fatigue remained an issue, but not because of the tendons. Over half an hour of nonstop pulsing, the muscle tired and its motion dropped. Similar wear occurs in designs without tendons. The key finding was that the synthetic links stayed intact throughout thousands of contractions.

The team then placed the units on a much stiffer robot frame shaped like a two-fingered gripper. In this tougher setup, the advantage of tendons became clear. The system transmitted about 29 times more useful force than on a softer frame. This confirmed that tendons allow living muscle to work with rigid machines that would otherwise tear it apart.

Why it matters

One of the most striking results was improved efficiency. With older designs, much of the muscle worked only as a fastener rather than a motor. The new setup let nearly all the tissue focus on pulling. Power output per unit of weight rose more than tenfold.

“Our goal is to make muscle actuators easier to use, like off the shelf parts,” said Ritu Raman, lead author of the study and an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at MIT. “We are introducing artificial tendons as interchangeable connectors between muscle actuators and robotic skeletons.”

Her vision goes beyond a single gripper. Because each muscle–tendon unit is modular, the same part could drive many types of machines. Engineers could combine units like building blocks to create more complex systems.

MIT colleagues also played key roles. Professor Xuanhe Zhao helped design the hydrogel, while Professor Martin Culpepper contributed to the mechanical design of the gripper. Graduate students and postdoctoral researchers assembled and tested the system.

Outside experts took note. Simone Schürle-Finke, a biomedical engineer at ETH Zürich, said the work “successfully merges biology with robotics” by solving a problem that has limited earlier designs.

The study does come with limits. Only one tendon material was tested, and the artificial joints do not yet copy the gradual change in stiffness found in real tissue. Long term effects on living cells remain unknown. For now, the muscles come from a mouse cell line. Using human cells could improve performance but adds complexity.

Still, the basic idea stands. By copying how your own body joins muscle to bone, engineers have taken a major step toward robots powered by living tissue that are strong, efficient and adaptable.

Practical Implications of the Research

The artificial tendon system could change how small robots are built. In medicine, muscle powered tools may someday assist with delicate tasks inside the body, such as moving tissue or delivering drugs. In exploration, tiny machines might enter spaces too dangerous for people, then heal minor damage on their own and keep working.

In research, the units offer a new way to study how living muscle performs when linked to machines, which may reveal insights about injury, fatigue and repair in human tissue.

As materials improve and control systems advance, these designs could lead to a new class of machines that combine the strength of engineering with the adaptability of biology.

Research findings are available online in the journal Advanced Science.

Related Stories

- First-ever multi-directional artificial muscles could revolutionize robotics

- Cutting-edge synthetic skin and a new specialized AI enables robots to sense pain

- Robots are safer and softer thanks to new artificial ‘muscles’

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer