Most Europeans had dark skin until 3,000 years ago, study finds

Ancient DNA reveals most Europeans had dark skin until 3,000 years ago

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Ancient DNA from hundreds of graves shows dark skin dominated Europe for most of its history. (CREDIT: RTE)

For most of Europe’s history, the people who lived there did not resemble the pale figures often shown in history books. New genetic research now shows that dark skin, dark hair, and dark eyes dominated Europe for tens of thousands of years and that lighter traits became common only very recently.

When you picture early Europeans, you might imagine icy landscapes filled with blue-eyed faces. A major DNA study challenges that image and asks you to rethink it from the ground up.

Researchers at the University of Ferrara in Italy studied the genomes of 348 people who lived between 45,000 and 1,700 years ago across Europe and western Asia. Their findings show that about 63% of ancient Europeans had dark skin. Only about 8% had pale skin. The rest had tones in between.

Dark Skin Was the Rule, Not the Exception

The oldest people in the study lived more than 40,000 years ago. Nearly all of them had dark eyes, dark hair, and dark skin. They were not so different from their ancestors in Africa.

Even thousands of years later, these traits remained common. In the Mesolithic period, between 14,000 and 4,000 years ago, dark skin still dominated Europe. Only a few people in places like Sweden and France showed lighter tones.

One rare individual from Sweden, known as NEO27, stood out about 12,000 years ago. That person had blue eyes, blond hair, and light skin. But the exception proved the rule. Most of their neighbors still carried darker features.

The Neolithic period brought farming and migration from Anatolia, now modern Türkiye. With farmers came new genes, including some tied to lighter skin. Even then, change was slow. Dark eyes and dark hair remained common across Europe for several thousand more years.

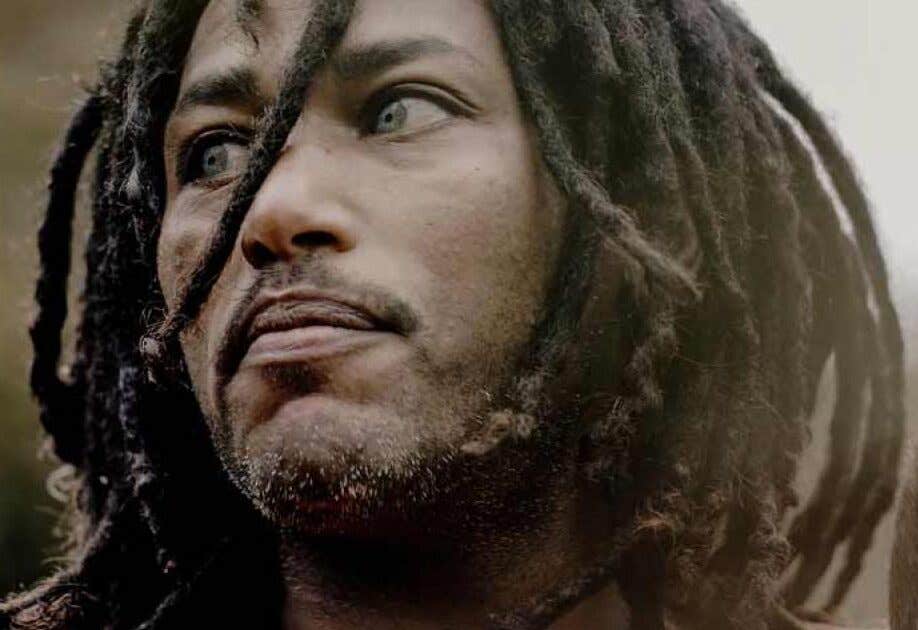

Faces You Thought You Knew

Famous ancient Europeans fit this updated picture.

Ötzi the Iceman, who died over 5,000 years ago in the Alps, had darker skin than many modern southern Europeans. “It’s the darkest skin tone that has been recorded in contemporary European individuals,” anthropologist Albert Zink, study co-author and head of the Eurac Research Institute for Mummy Studies in Bolzano explained when Ötzi’s genetic analysis was released.

Another surprise came in 2018 when scientists analyzed Cheddar Man, Britain’s oldest complete skeleton. The 10,000-year-old man had dark brown skin and blue eyes. These results shocked the public at first, but they now look far less unusual.

By the Bronze Age, between about 7,000 and 3,000 years ago, lighter traits appeared more often. Still, dark skin did not vanish. Both appearance types existed side by side across Europe, Central Asia, and parts of the Middle East.

Even during the Iron Age, from about 3,000 to 1,700 years ago, dark features remained common in places such as Italy, Spain, and Russia.

Why Did Skin Color Change So Slowly?

Light skin is often explained as an adaptation to weak sunlight. Paler skin absorbs more ultraviolet light, which helps the body produce vitamin D.

That explanation still matters. But it is not the whole story.

Diet also played a role. Early Europeans relied heavily on meat, fish, and wild foods rich in vitamin D. When farming spread, diets changed. Grain-based foods lack vitamin D. Over time, lighter skin may have helped boost vitamin D production when food could not.

Population mixing did the rest. As farmers migrated from the east, they introduced new genetic variants tied to lighter skin. One key variant appeared in the genes TYR and SLC24A5. These variants were not present in the oldest Europeans but showed up later in individuals with lighter traits.

Researchers also confirmed that modern Europeans did not inherit pale skin from Neanderthals, despite shared ancestry. Lighter skin evolved independently within Homo sapiens.

How Scientists Read Color from Ancient DNA

Studying ancient appearance is not simple. Old DNA breaks easily. It is often incomplete and badly damaged. That makes predicting skin or eye color difficult.

For years, scientists relied on a system called HIrisPlex-S. It predicts pigmentation from 41 genetic locations. It works well with modern, clean DNA.

Ancient DNA is different.

When DNA coverage is low, missing information must be filled in. Many scientists used a shortcut called imputation, which guesses missing letters using modern DNA databases.

The Ferrara team tested that method. They found it often produced wrong answers, especially for skin color.

Instead, the researchers used a probabilistic approach. Rather than choosing one guess, they ran thousands of possible genetic combinations. A trait was accepted only if it appeared in 90% of those trials.

When coverage fell below eight DNA reads per location, errors spiked. Imputation performed worst. The probabilistic approach performed best, though it still had limits.

The difference matters because many ancient portraits rely on poor-quality DNA.

Why the Method Matters

If the methods are flawed, the faces are too.

When scientists show ancient Europeans as pale by default, they may be building fiction from thin data. Overconfident reconstructions shape public ideas about race, history, and identity.

This study urges caution. It asks researchers to admit uncertainty instead of hiding it and to avoid forcing modern assumptions onto prehistoric people.

Ancient humans were not a single type. They were diverse, mobile, and shaped by their surroundings.

Practical Implications of the Research

This research changes how you understand European history. It shows that light skin is a recent trait, not an ancient one. That insight challenges harmful myths that link appearance to belonging or worth.

In forensic science, these findings improve accuracy. Investigators working with damaged DNA must rethink how they interpret genetic clues, especially in criminal or disaster cases.

Museums and textbooks will likely change, too. Future generations may see reconstructions that reflect genetic truth rather than long-held assumptions.

For health researchers, understanding how skin color evolved helps explain how genes, diet, and sunlight affect disease risk and vitamin D levels today.

Above all, the work reminds you that human appearance is fluid. It shifts with climate, culture, and movement. The past was richer and more complex than you were taught.

Research findings are available online in the journal PNAS.

Related Stories

- New AI model reveals key genetic, social, and lifestyle factors impacting skin cancer risk

- Surprising discovery connects skin tone, genetic ancestry and skin cancer

- Neanderthal DNA sheds new light on the structure of the modern human face

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.