Mysterious structures within Earth’s mantle may explain why we exist

New research shows Earth’s core may have shaped huge deep-mantle structures that helped make the planet livable.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

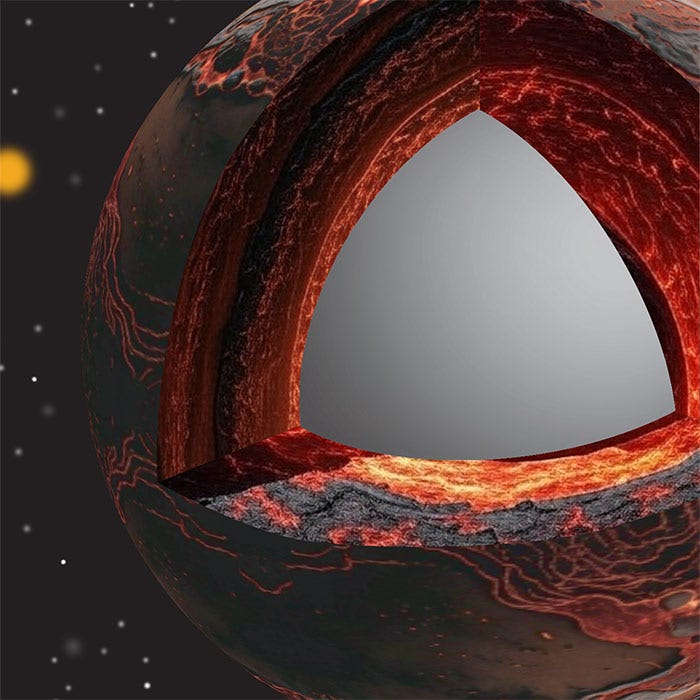

The illustration shows a cutaway revealing the interior of early Earth with a hot, melted layer above the boundary between the core and mantle. Scientists think some material from the core leaked into this molten layer and mixed in. Over time, that mixing helped create the uneven structure of Earth’s mantle that we see today. (CREDIT: Yoshinori Miyazaki)

Far below your feet, nearly 1,800 miles beneath oceans and continents, Earth carries two massive scars from its violent youth. They are so large they rival continents in size, yet no human will ever see them. Scientists call them large low-shear-velocity provinces, or LLSVPs, and they sit at the border between Earth’s mantle and its blazing hot core. One lurks under Africa, the other under the Pacific Ocean.

Nearby are thinner, stranger features known as ultra-low velocity zones, or ULVZs. These look like puddles of partially melted rock clinging to the top of the core. Both types of regions slow down earthquake waves, which tells scientists that something down there is different from the rest of the mantle.

For decades, researchers have wondered what these hidden giants mean and why they exist at all. A new study in Nature Geoscience suggests they may be ancient leftovers from Earth’s chaotic birth, shaped not only by melting rock but also by material leaking from the core itself.

“These are not random oddities,” said Yoshinori Miyazaki, an assistant professor in Earth and planetary sciences at Rutgers University and lead author of the study. “They are fingerprints of Earth’s earliest history. If we can understand why they exist, we can understand how our planet formed and why it became habitable.”

A Planet Once Made of Fire

Early Earth did not look like the blue world you know today. After a massive collision that formed the Moon, much of the planet was likely covered by a global ocean of magma. This sea of molten rock slowly cooled and hardened, creating the layered interior scientists study today.

For years, models suggested this magma ocean should have frozen into tidy chemical layers, like oil separating from water. But seismic images of Earth’s interior tell a messier story. Instead of neat layers, the bottom of the mantle holds giant piles of unusual rock and thin patches that seem partly molten.

“That contradiction was the starting point,” Miyazaki said. “If we start from the magma ocean and do the calculations, we don’t get what we see in Earth’s mantle today. Something was missing.”

When the Core Joins the Conversation

The missing ingredient, the team argues, is the core itself.

Unlike earlier ideas, this new work suggests Earth’s core did not stay sealed away after it formed. Over billions of years, certain elements may have slowly escaped upward. The core contains silicon, magnesium and oxygen dissolved in liquid metal. As the core cooled, tiny solid particles of these materials likely formed and drifted toward the boundary with the mantle.

If the mantle was still molten when those particles arrived, they would have dissolved into the magma like sugar in hot coffee. That steady trickle of new material changed the chemistry of the deep mantle and altered how it froze.

The scientists call this hybrid layer a “basal exsolution contaminated magma ocean.” It is a mouthful, but the idea is simple. Earth’s deep magma ocean was not pure. It was continually flavored by the core.

The models show this extra input kept the bottom of the mantle from becoming too dense and too simple in composition. Instead of forming one thick heavy blanket around the core, the material was free to clump into piles.

Those piles look a lot like today’s giant underground structures.

Making Sense of Strange Rock and Volcano Clues

This idea also helps explain clues carried to the surface by volcanoes.

Lava from places like Hawaii and Iceland has a chemical signature different from lava at mid-ocean ridges. Some of these island volcanoes release helium that seems more ancient than the planet’s surface rocks. They also show odd ratios of tungsten and silicon isotopes that hint at a source deep inside Earth.

According to the study, small amounts of core-influenced material rising in plumes from the mantle could create those signals. When less than one percent of this deep material mixes with normal mantle rock, it can reproduce the odd patterns measured in some island lavas.

The most extreme silicon readings still puzzle scientists. Those may involve other processes that remain unclear. But the overall match is strong enough that the link between the deep mantle and the core now seems far more than coincidence.

“This work is a great example of how combining planetary science, geodynamics and mineral physics can help us solve some of Earth’s oldest mysteries,” said Jie Deng of Princeton University, a co-author of the study. “The idea that the deep mantle could still carry the chemical memory of early core interactions opens new ways to understand Earth’s evolution.”

A New View of Earth’s Living Heart

The findings go beyond rocks and minerals. They speak directly to why Earth became a place where life could grow.

Movement inside the planet fuels volcanoes, rebuilds land and shapes oceans. Heat rising from the depths drives plate tectonics, which recycles carbon and stabilizes the climate over long ages.

Miyazaki believes core-mantle mixing may have helped Earth cool in just the right way. Too fast, and the planet might have frozen. Too slow, and it could have turned into a runaway furnace.

“Earth has water, life and a relatively stable atmosphere,” he said. “Venus has an atmosphere this thick with carbon dioxide, and Mars barely has one at all. We don’t fully understand why. But what happens inside a planet, how it cools and how its layers evolve, could be a big part of the answer.”

The deep structures also appear tied to surface activity. Seismic imaging suggests rising plumes from these underground piles may feed volcano chains at the surface. In that sense, the planet’s hidden heart still speaks through fire and smoke.

A Story Still Being Written

This study does not close the book on Earth’s interior. It opens new chapters.

Scientists still need sharper images of the mantle and better measurements of exotic minerals at high pressure. Future experiments will test how these materials behave under conditions no lab naturally creates. More data from earthquakes will also sharpen the picture of what lies thousands of miles down.

Yet each step brings you closer to understanding the engine beneath your world.

“Even with very few clues, we’re starting to build a story that makes sense,” Miyazaki said. “This study gives us a little more certainty about how Earth evolved and why it’s so special.”

Practical Implications of the Research

This research reshapes how scientists understand Earth’s engine. It links the core, mantle and surface as parts of one evolving system rather than isolated layers. That helps researchers build better models of volcanic risk, long-term climate stability and heat flow inside the planet.

In the future, it could improve predictions of where deep mantle plumes rise and how continents shift over time. It also offers a new guide for studying other planets, helping scientists judge whether distant worlds might hold conditions friendly to life.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Related Stories

- 4.5 billion-year-old proto-Earth fragments found in Earth’s mantle

- Scientists discover strange mantle zones that challenge current understanding of plate tectonics

- First-ever rocks recovered from the Earth’s mantle could reveal secrets of Earth’s history

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Mac Oliveau

Writer

Mac Oliveau is a Los Angeles–based science and technology journalist for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication focused on uplifting, transformative stories from around the globe. Passionate about spotlighting groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, Mac covers a broad spectrum of topics including medical breakthroughs, health and green tech. With a talent for making complex science clear and compelling, they connect readers to the advancements shaping a brighter, more hopeful future.