Nearby red giant challenges how stars spread the building blocks of life

Detailed observations of the nearby red giant R Doradus reveal that dust grains lack the force needed to drive stellar winds, challenging long-standing theory.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

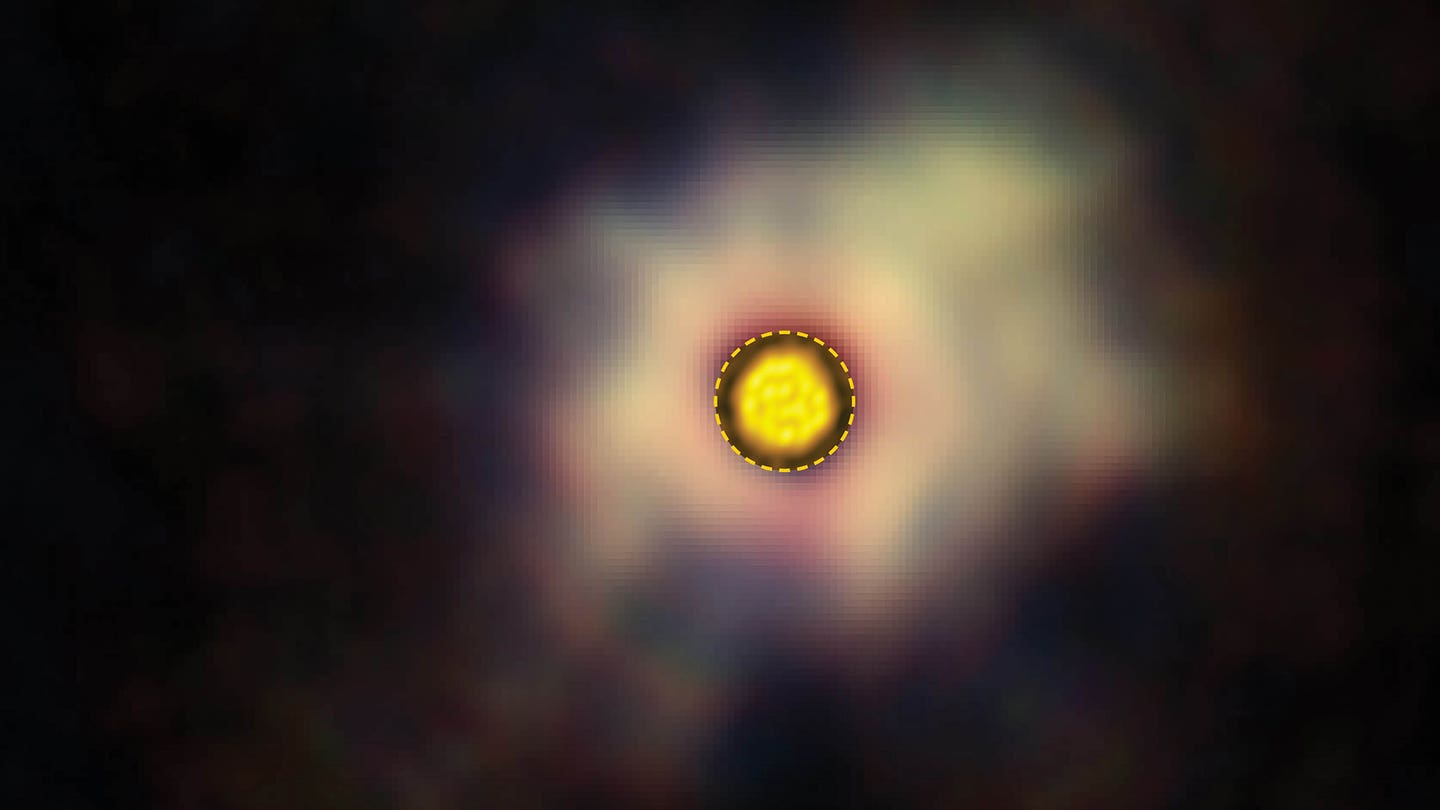

Dust clouds reflect starlight around the star R Doradus. (CREDIT: ESO/T. Schirmer/T. Khouri; ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO))

You are watching a long-held idea in stellar physics face serious scrutiny. Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, working with colleagues at the University of Gothenburg, have taken a close look at how aging stars shed material into space. Their focus is R Doradus, one of the closest and brightest red giant stars known. What they found challenges a decades-old explanation for how these stars drive powerful winds that seed the galaxy with life-forming elements.

The research team, led by astronomers Theo Khouri and Thiébaut Schirmer at Chalmers, used some of the world’s most advanced telescopes and computer models. Their results were published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics. Together, the observations and simulations show that dust grains alone cannot explain how winds escape from oxygen-rich red giant stars like R Doradus.

At this late stage of stellar life, stars similar to the Sun expand into what astronomers call asymptotic giant branch stars. These bloated red giants have dense cores, active nuclear shells, and vast outer layers that pulse and churn. For years, scientists believed that starlight pushing on newly formed dust grains lifted gas away from the star, creating a slow but steady wind.

Why Oxygen-Rich Stars Are a Problem

That idea has always been harder to defend for oxygen-rich red giants. In these stars, dust is thought to form first as aluminium oxide, then grow into silicate grains that contain magnesium and silicon. Observations support the presence of these materials close to the star.

The trouble is that detailed calculations show iron-free silicate grains do not absorb enough light to feel a strong outward push. Iron-bearing silicates would absorb more energy, but they would heat up and evaporate before they could help launch a wind. A workaround suggested that if dust grains grew large enough, they could scatter light instead of absorbing it and still gain momentum.

High-resolution imaging later confirmed that grains of roughly the right size exist around oxygen-rich red giants. The unanswered question was whether those grains could truly overcome gravity under realistic conditions.

R Doradus as a Natural Laboratory

R Doradus offers a rare opportunity to test that question. Located only about 59 parsecs from Earth, the star appears large on the sky, allowing astronomers to resolve the region where dust forms and winds begin. R Doradus varies in brightness with pulsation periods of 175 and 332 days and loses mass at a modest but steady rate.

Earlier studies revealed a complex environment around the star, including rotating gas, asymmetries, and large convective features. Many of those investigations matched observed polarization patterns but stopped short of testing whether the dust could actually drive a wind.

This study goes further. It combines detailed dust modeling with independent measurements of gas density. The goal is simple but demanding: check whether dust that matches the images can also satisfy chemical limits and provide enough force to escape the star’s gravity.

Watching Starlight Scatter off Dust

The team observed R Doradus in November 2017 using the SPHERE instrument on the Very Large Telescope in Chile. They measured polarized light at three visible wavelengths, allowing them to trace how starlight scatters off dust grains close to the star.

After careful data processing, the images revealed a bright arc of polarized light surrounding an unpolarized stellar core. This arc marks the region where dust grains scatter light efficiently. The apparent size of the star also changed with wavelength, an effect caused by dust and molecules altering the light’s path.

To interpret these patterns, the researchers treated the star’s size at each wavelength as a variable. This step proved critical for accurately modeling how radiation interacts with dust.

Building and Testing Thousands of Models

"Using advanced radiative transfer software, our team built three-dimensional models of R Doradus and its dusty surroundings. We tested different dust compositions, including magnesium silicates, aluminium oxide, and iron-bearing silicates. Both ideal spherical grains and more irregular shapes were considered," Khouri shared with The Brighter Side of News.

"Instead of guessing one solution, we explored a vast grid of possibilities. Grain size, dust density, and how density changes with distance were all varied within physically realistic limits. Models that failed to reproduce the observed polarization or intensity patterns were rejected," he continued. "Only those that matched the data across all wavelengths and distances survived."

Even then, the models faced another hurdle: chemistry.

When Chemistry Sets Hard Limits

Stars have limited supplies of elements like silicon and aluminum. Observations of R Doradus show that only a small fraction of silicon is locked into dust. Any realistic model must respect that constraint.

When the surviving dust models were combined with measured gas densities, the picture became clear. Some dust configurations could exist without violating chemical limits, especially close to the star. However, farther out, the models demanded more silicon in dust than the star actually provides.

Aluminium oxide could plausibly form a thin inner shell. Magnesium silicates could explain scattered light farther out. Iron-bearing silicates remained mostly theoretical, as they would not survive the intense heat.

Not Enough Force to Drive a Wind

The final test asked whether radiation pressure on dust could beat gravity. For a dust-driven wind to work, the outward force must exceed the star’s pull.

It never did.

Across all realistic models, the radiative push fell far short. Even when dust mass was pushed to the highest chemically allowed levels, the force remained too weak. Models that could produce enough force required unrealistic levels of element depletion and ignored thermal destruction.

“We thought we had a good idea of how the process worked. It turns out we were wrong. For us as scientists, that’s the most exciting result,” Khouri said.

Schirmer added, “Dust is definitely present, and it is illuminated by the star. But it simply doesn’t provide enough force to explain what we see.”

Rethinking How Giant Stars Shed Material

The findings suggest that dust plays a supporting role rather than leading the process. Other forces must help lift material from the star. Previous observations with the ALMA telescope showed giant convective bubbles rising and falling on R Doradus.

“Even though the simplest explanation doesn’t work, there are exciting alternatives to explore,” said Wouter Vlemmings, a co-author and professor at Chalmers. Pulsations, convection, and brief bursts of dust formation may all contribute.

The classic picture of dust-driven winds in oxygen-rich red giants is no longer enough.

Practical Implications of the Research

Understanding how red giant stars lose mass matters far beyond stellar physics. These winds enrich galaxies with carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and other elements essential for planets and life.

By showing that dust alone cannot launch these winds, the study forces scientists to rethink how material circulates through galaxies.

Future research can now focus on combined effects, such as pulsations and convection, leading to more accurate models of stellar evolution and chemical enrichment.

Over time, this improved understanding helps explain the origins of planetary systems and the ingredients that make life possible.

Research findings are available online in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Related Stories

- Is interstellar object 3I/ATLAS an alien probe? Harvard physicist sparks debate

- New interstellar discovery reveals origin of our solar system

- Scientists propose simple new way to spot alien life in the universe

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.