New fossil evidence places early humans in Eurasia 2 million years ago

New clues about our earliest ancestors suggest they may have reached Eurasia sooner than scientists once thought.

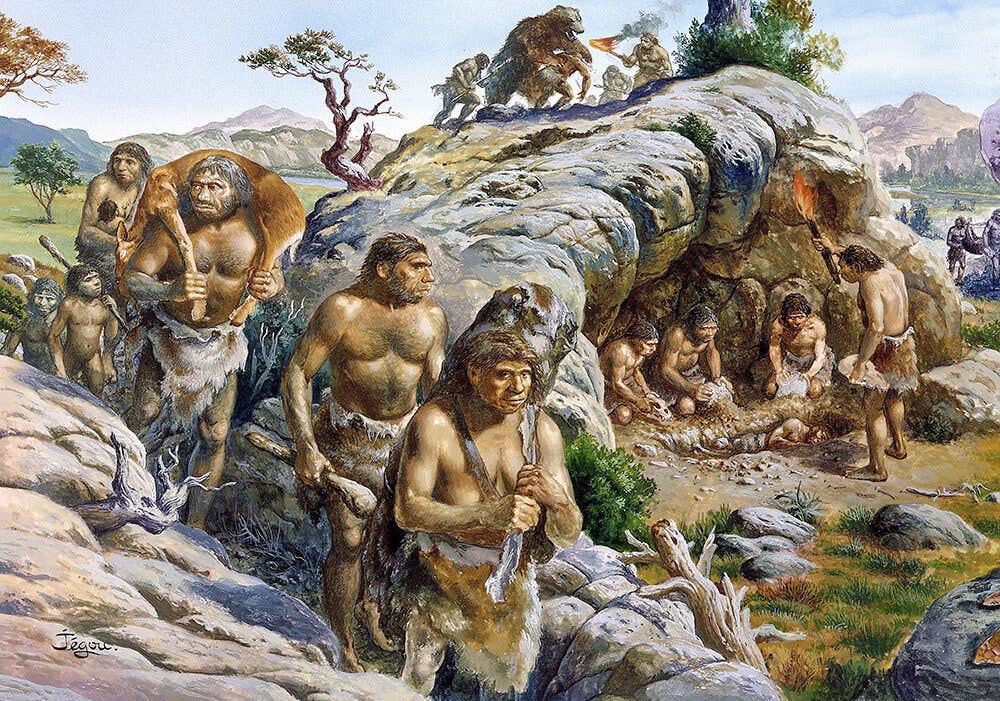

Fossils from Grăunceanu, Romania, reveal hominins migrated to Eurasia nearly 2 million years ago. (CREDIT: Christian Jegou/Science Source)

New clues about our earliest ancestors suggest they may have reached Eurasia sooner than scientists once thought. Fossils found in Romania hint that hominins left Africa nearly two million years ago—well before previous estimates.

The evidence comes from Grăunceanu, a fossil site in the Olteț River Valley. This site predates Georgia’s Dmanisi remains by about 200,000 years. It suggests our ancient relatives began spreading across the globe earlier than once believed.

Ancient Bones, New Revelations

Grăunceanu lies in the Dacian Basin, near the Carpathian Mountains. The region is packed with rich fossil beds from the Early Pleistocene, spanning between 2.2 and 1.3 million years ago. It's a window into a time when early humans may have started exploring new frontiers.

In the 1960s, scientists dug up thousands of bones in this area. The site painted a picture of a forest-steppe full of ancient beasts like mammoths, saber-toothed cats, giraffes, and pangolins. Although no hominin bones were found, something else caught their eye.

On close inspection, researchers noticed tool marks etched into animal bones. Over 5,000 fossils were studied across decades. At least 20 showed cut marks likely made by stone tools—clear signs of butchering and early human activity.

Using uranium-lead dating, scientists confirmed the bones were at least 1.95 million years old. These findings push back the timeline for human migration into Eurasia and reshape our understanding of early human history.

Related Stories

Evidence Beyond Bones

Researchers faced challenges working with fossils excavated over 50 years ago. Connecting the cut-marked bones to hominin activity required thorough analysis and collaboration among experts.

Sabrina Curran, an anthropologist at Ohio University, spearheaded the study alongside a multidisciplinary team that included Claire Terhune from the University of Arkansas and Alexandru Petculescu of Romania’s Emil Racoviță Institute of Speleology. The group also collaborated with the Smithsonian Institution and Colorado State University.

“We didn’t initially expect to find much,” Curran shared. “But during a routine check of the collections, we found several cut-marked bones. This led to further investigation and the discovery of deliberate butchering activities.”

The study highlights the adaptability of early hominins. Stable isotope analysis of a horse fossil from Grăunceanu revealed that the region experienced seasonal temperature changes and higher rainfall, contrasting with the drier African savannas where hominins originated. These environmental conditions likely presented new challenges and opportunities for survival.

A Broader Context of Dispersal

Before this discovery, the site of Dmanisi in Georgia, dated to about 1.8 million years ago, held the title for the earliest known hominin presence outside Africa. The Grăunceanu findings suggest hominins were in Eurasia even earlier, spreading across diverse landscapes. This raises questions about how these ancient humans adapted to environments vastly different from those of their African homeland.

Grăunceanu’s fossil record provides a snapshot of a complex ecosystem. It shows hominins shared their environment with woolly rhinos, giant deer, ostriches, and other fauna. The variety of species indicates the region’s ecological richness, which may have supported early human survival.

The lack of stone tools at Grăunceanu posed a challenge for researchers. However, similar tools were previously documented at nearby sites like Dealul Mijlociu, reinforcing the likelihood of hominin activity in the region. These tools, combined with the cut-marked bones, present a compelling case for hominin dispersal into Europe around two million years ago.

Implications for Human Evolution

“This discovery is a pivotal moment in understanding human prehistory,” said Curran. “It demonstrates that early hominins had already begun to explore and inhabit diverse environments across Eurasia, showing an adaptability that would later play a crucial role in their survival and spread.”

The findings also spark debate among paleoanthropologists. Claire Terhune noted the scrutiny their work has faced, given the implications of such an early presence in Eurasia. “The field of paleoanthropology can be contentious. People get really fired up about human ancestors,” she explained. “We’ve been meticulous in documenting the cut marks to ensure the evidence is indisputable.”

The study underscores the complexity of human evolution, challenging long-held assumptions about when and how early humans left Africa. It highlights the resilience and resourcefulness of hominins, who thrived in new and changing environments. This adaptability may have been key to their eventual global dispersal.

The Grăunceanu site offers a glimpse into a critical chapter of human history. By pushing the timeline of hominin dispersal into Eurasia back by 200,000 years, it opens the door to new questions about early migrations. What drove these ancient ancestors to leave Africa? How did they navigate and survive unfamiliar terrains? And what other traces of their journey remain undiscovered?

As Curran put it, “The history of human evolution is far more complex and intricate than we could have imagined, and we are just beginning to uncover the many chapters of that story.”

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.