New global map finds recent tectonic activity across the Moon’s surface

Newly mapped lunar ridges may mark young faults in the Moon’s maria, raising new questions about moonquakes near landing zones.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

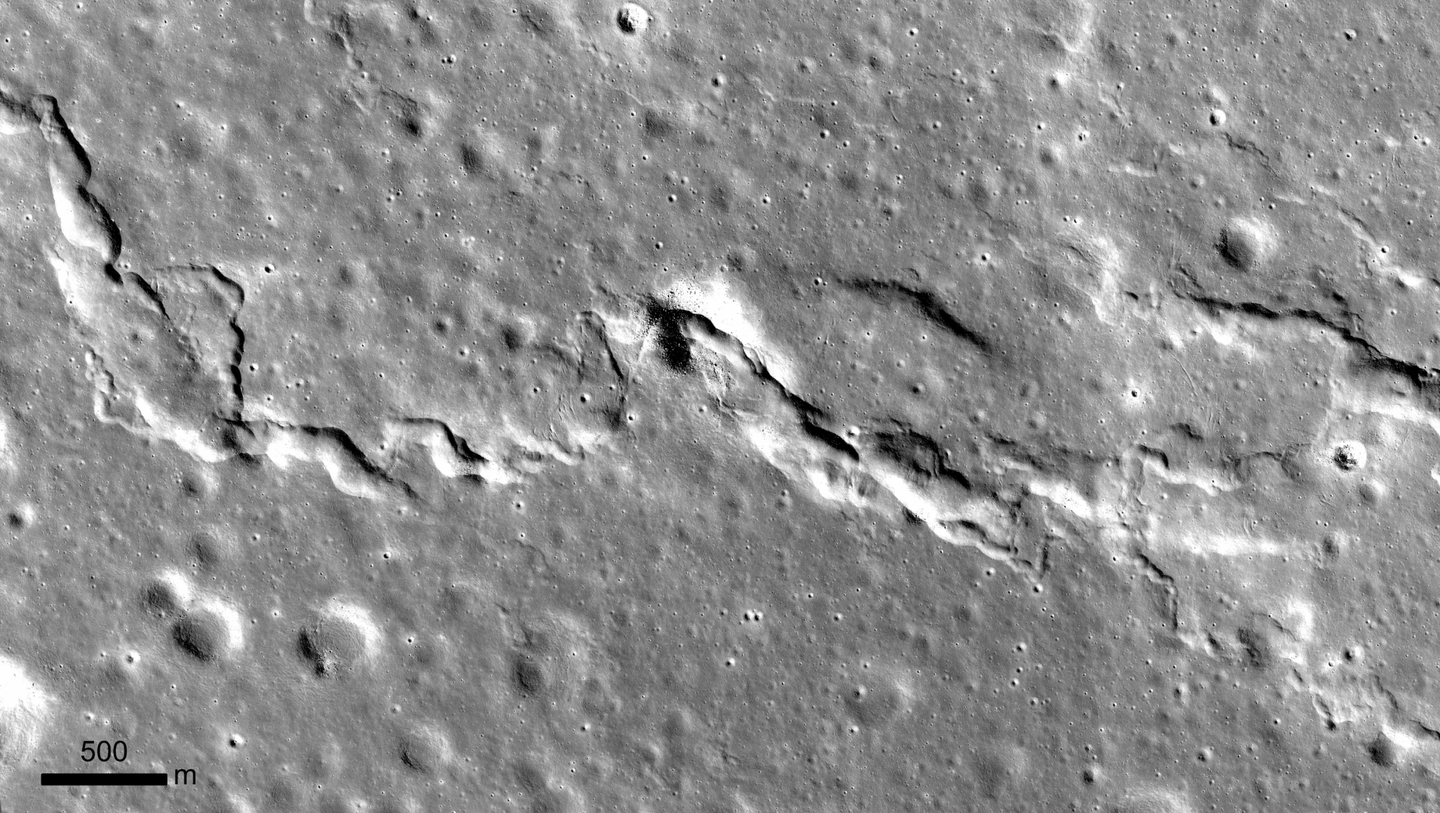

A small mare ridge in Northeast Mare Imbrium taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera. (CREDIT: NASA / GSFC / Arizona State)University

Low, winding ridges run across the Moon’s dark plains like faint seams in cooled wax. They are easy to miss in a wide photo. Up close, they look like the surface has been gently pushed from below.

A new study argues those ridges are not just old scars. Many are surprisingly young, and they show up across much more of the Moon than scientists had pinned down before.

In The Planetary Science Journal, researchers at the National Air and Space Museum’s Center for Earth and Planetary Studies and collaborators produced the first global map and analysis of “small mare ridges,” or SMRs.

The work reports that these features are widespread across the lunar maria, the broad, dark basalt plains, and that they formed recently in lunar terms. The same stresses that build these ridges can also trigger moonquakes, the authors say, which puts them on the list of hazards future missions may need to consider.

A shrinking Moon leaves a different kind of fingerprint

The Moon and Earth both flex and crack, but they do it in different ways. Earth’s surface is broken into plates that grind, collide, and spread apart. The Moon’s crust is not divided into plates, yet it still carries internal stresses that shape the landscape.

One of the most common tectonic landforms on the Moon is the lobate scarp, a ridge created when the crust compresses and one block of material pushes up and over another along a fault. Lobate scarps are mainly found in the lunar highlands. Earlier work found they formed within the last billion years, which the source describes as the last 20% of lunar history.

In 2010, co-author Tom Watters, a senior scientist emeritus at the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, reported evidence that the Moon is slowly shrinking. That global contraction helped explain the lobate scarps in the highlands. But not all young compression features fit neatly into that picture.

SMRs are part of what was missing.

They form from the same kind of compressional forces as lobate scarps, but they appear only in the maria. That difference matters because the maria cover large portions of the nearside and some patches of the farside. If young faults also thread through these plains, the Moon’s most familiar “landing” terrain may be more tectonically active than many people assume.

A catalog that suddenly got much bigger

The team built what it calls the first exhaustive catalog of SMRs. In the nearside maria alone, they identified 1,114 new SMR segments. That raised the known total of SMR segments across the Moon’s maria to 2,634.

To find them, the researchers first searched for candidate ridges in a global mosaic from the Kaguya Terrain Camera, then mapped the features in much finer detail using high-resolution images from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera Narrow Angle Cameras. They used a set of criteria to decide what counted as an SMR, including an elongated, sinuous ridge with positive relief and a distinct, undegraded boundary with surrounding terrain.

Not everything made the cut. The paper notes that 198 features from a 2022 catalog and 296 features from a 2025 catalog were excluded from the updated map because they were too degraded to meet the morphology criteria used here.

The resulting map shows SMR clusters in all major nearside mare deposits. On the farside, about half of mare deposits show clusters, based on the study’s comparison to earlier farside mapping.

The team also split the ridges into two groups: “stand-alone” SMRs and “ridge-adjacent” SMRs. Stand-alone features are not tied to a larger, older wrinkle ridge. Ridge-adjacent features sit next to, or on top of, those older structures. Out of 2,634 SMR segments, 1,058 were classified as stand-alone and 1,438 as ridge-adjacent. The study says that 57.6% of SMRs are spatially associated with preexisting tectonic structures, suggesting older structures often help localize where new, small faults appear.

How young is “young” on the Moon?

The authors argue that SMRs belong among the youngest tectonic features on the Moon. They estimate surface “seismic resetting” ages for five nearside SMR clusters that range from about 50 million to 310 million years.

The idea behind seismic resetting is that fault slip and moonquakes can erase small impact craters near a fault. The team assumed SMR-related quakes could wipe out craters smaller than 100 meters in nearby areas, which would alter the crater size-frequency distribution used for dating. The paper also notes an uncertainty here: the moonquake magnitude needed to erase craters is “poorly constrained.”

Even with that caveat, the ages cluster in a striking range. The study reports an average SMR seismic resetting age of 124 million years. That is close to the average age for lobate scarps, 105 million years, reported in a prior investigation cited in the source.

Whether those ages mark the ridges’ first formation or their most recent activity is not clear, the authors say. They point to evidence consistent with incremental, linear growth rather than a single slip event.

Cole Nypaver, a post-doctoral research geologist at the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies and the paper’s first author, framed the work as a shift in scale and coverage. “Since the Apollo era, we’ve known about the prevalence of lobate scarps throughout the lunar highlands, but this is the first time scientists have documented the widespread prevalence of similar features throughout the lunar mare,” Nypaver said. He added that a global view of recent lunar tectonism can sharpen understanding of the Moon’s interior, its thermal and seismic history, and “the potential for future moonquakes.”

Watters put it more bluntly: “Our detection of young, small ridges in the maria, and our discovery of their cause, completes a global picture of a dynamic, contracting moon,” he said.

Peeking under the ridge, then counting the strain

To connect these ridges to specific fault geometries, the team modeled a subset of SMRs using elastic dislocation modeling with USGS Coulomb 3.4 software. That modeling relied on stereo-derived digital terrain models from Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter images.

The sample is limited: 13 SMR segments across seven clusters, chosen largely because terrain model coverage was available. For those modeled faults, the dip angle ranged from 30° to 45°, with an average of 38°. Estimated slip ranged from 15 to 110 meters, averaging 44.7 meters. Fault depths ranged from 30 to 200 meters, averaging 101.2 meters.

The paper compares those results to prior modeling of lobate scarps, which found deeper faults in a small sample. The authors offer a few possible explanations for the depth difference, including the mechanical strength of mare basalts, uncertainty about the mare regolith-to-bedrock boundary, and the chance that sample choices in older lobate scarp modeling favored larger features. The study also flags another limitation: SMRs can vary in shape along their length, so any one model may not capture the full complexity of an individual ridge.

The team also estimated how much the maria have strained due to this late-stage contraction. Using displacement-length relationships from 50 SMR segments and the mapped lengths of all SMR segments, they estimate an areal contractional strain of 3.41 × 10⁻⁵ to 3.95 × 10⁻⁵, or 0.0034% to 0.0040%, across the maria. The calculation uses a total mare basalt surface area of 6,151,238 square kilometers. The paper notes the strain is not evenly distributed, with higher values in nearside mare regions and the highest in Oceanus Procellarum.

The Moonquake question gets wider

Watters’ earlier work linked lobate scarp activity to shallow moonquakes. If SMRs form from the same global stress fields and similar thrust-fault mechanics, then the maria may host their own widespread set of quake sources.

The study points to Apollo-era seismic observations for context. It notes that shallow moonquakes in the magnitude range of 1.6 to 4.2 were detected by the Apollo Lunar Seismic Experiment, and suggests quakes in that range could contribute to crater erasure near active faults.

The authors argue that young tectonics and related seismicity are not confined to highlands terrain. They also list future mission concepts that could benefit from the new map, including the Lunar Geophysical Network, the Lunar Environment Monitoring Station, and the Farside Seismic Suite. Nypaver also points to Artemis as part of a broader push that will bring more data and higher stakes for understanding lunar hazards.

Research findings are available online in The Planetary Science Journal.

The original story "New global map finds recent tectonic activity across the Moon’s surface" is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- Earth’s magnetic field funneled atmospheric elements to the Moon over billions of years

- Chang’e-6 samples show ancient lunar impacts left rust on the Moon

- Moon's largest impact crater helps explain why the near side and far side look so different

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.