New injectable gel could help scarred vocal cords sing again

McGill scientists created a long lasting vocal cord gel that may help scarred voices heal and reduce repeat injections.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

A McGill University team has engineered a new injectable hydrogel that stays in the vocal cords for weeks, resists breakdown, and may help damaged tissue heal instead of scar. If future trials succeed, it could give people who lose their voice a safer, longer lasting way to speak and sing again. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

For many people, the sound of their own voice feels like part of who they are. When that voice turns rough or disappears after an injury, it can feel like losing a piece of identity. Now researchers at McGill University have created a new injectable gel that may give damaged vocal cords a better chance to heal instead of scar.

Why Vocal Cord Scarring Is So Hard To Treat

Your vocal cords are thin folds of tissue that vibrate every time you speak or sing. They sit deep in the throat and face constant stress from talking, coughing, and swallowing. When they are injured by surgery, infection, acid reflux, smoking, or overuse, the tissue can scar. Once that scar forms, the vibration changes, and the voice may stay hoarse or weak for life.

Doctors can inject fillers into the cords to bulk them up and improve the sound. Those materials, however, usually break down quickly. That means you may need repeat injections every few months. Each procedure carries risk and can cause more irritation to already fragile tissue.

Voice problems are more common than many people realize. The U.S. National Institutes of Health estimates that roughly one in 13 adults has a voice disorder in any given year. The risk climbs in older adults, people who smoke or have chronic reflux, and anyone who uses their voice all day, such as teachers, singers, or call center staff.

A New Gel Designed To Last Longer

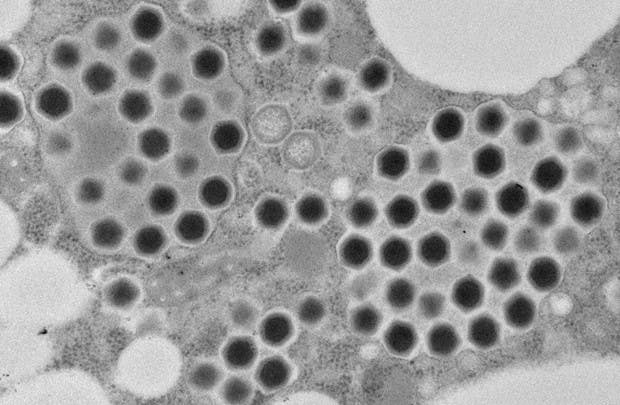

To tackle this problem, the McGill team engineered a new hydrogel that aims to stay in place for weeks rather than days. The material starts with natural tissue proteins. The researchers process those proteins into a fine powder, then turn the powder into a smooth gel that can pass through a needle.

On its own, this type of material tends to fall apart in the body. To change that, the scientists used a chemical strategy called click chemistry. It links the gel’s molecules together in a very controlled way, like snapping together tiny building blocks.

“This process is what makes our approach unique,” said co senior author Maryam Tabrizian, a professor in McGill’s Department of Biomedical Engineering. “It acts like a molecular glue, locking the material together so it doesn’t fall apart too quickly once injected.”

The result is a gel that behaves more like real vocal cord tissue. It remains soft and flexible enough to vibrate, but it is also strong enough to resist rapid breakdown.

Putting the Gel Through Early Tests

The study, published in the journal Biomaterials, described a series of preclinical tests in the lab and in animals. Researchers first studied how the gel handled stress in test tubes. They found that it held its structure for several weeks, outlasting the injectable materials currently used in clinics.

Next, they injected the gel into animal tissue. There, too, it remained stable for an extended period. That extra time is critical. It may give your injured vocal cords a longer window to rebuild healthy tissue instead of forming stiff scar.

The gel’s ingredients come from natural matrix proteins, which are the support structures that surround cells. Because of that, the material does more than simply fill space. It can provide signals that help cells move in, settle, and start repairing damage.

In earlier work, similar gels have encouraged new blood vessel growth and tissue remodeling in other body sites. In the vocal cords, those same traits could help restore the fine layered structure that gives a voice its smooth sound.

The Emotional Toll of Losing A Voice

Senior author Nicole Li Jessen brings both scientific training and personal experience to the project. She is a clinician scientist, a pianist, and someone who works closely with singers and other professional voice users.

“People take their voices for granted but losing it can deeply affect mental health and quality of life, especially for those whose livelihoods depend on it,” said Li Jessen, an associate professor in McGill’s School of Communication Sciences and Disorders.

If your work or art depends on your voice, even a small change can feel enormous. You may struggle to be heard in meetings, tire quickly when teaching, or fear that a cherished career on stage is ending. Even outside of work, many people feel isolated when they cannot speak comfortably with family and friends.

A treatment that protects the vocal cords and reduces repeat procedures could ease some of that burden. It would not only target the physical injury, but also support the emotional recovery that comes with being able to speak or sing again.

From Lab Bench To Future Clinic

The gel is still at an early stage. Before it reaches patients, the team wants to understand exactly how it behaves in the complex environment of the human larynx. The vocal cords vibrate hundreds of times per second when you speak. Any injected material must stretch and rebound with those rapid movements without tearing or clumping.

To explore this, the researchers plan to test the gel in computer models that mimic real voice vibration. These simulations will help them predict how the material moves, how long it lasts, and how it affects sound quality over time.

Once those models match what they see in lab tests, the group hopes to move toward human trials. If those trials succeed, the gel could become part of a minimally invasive procedure where a physician injects it through a fine needle into the damaged fold.

Instead of needing several treatments each year, patients might receive a single injection that stays put long enough to guide real healing. For you as a patient, that could mean fewer hospital visits, less risk, and a better chance of getting your voice back.

Practical Implications of the Research

This new hydrogel points toward a future in which voice loss after injury does not have to be permanent. By resisting breakdown for weeks, the material gives your vocal cords more time to rebuild themselves rather than forming dense scar. That shift could turn many current “patch” procedures into true regenerative treatments.

For people whose careers depend on their voice, a longer lasting, tissue friendly injection might help preserve work and income. Teachers could stay in classrooms longer without strain. Singers and actors might avoid early retirement due to chronic hoarseness. Older adults could keep clearer speech and stronger social ties.

The work also offers a broader template for regenerative medicine. The same click chemistry approach could help stabilize other injectable gels used in joints, skin, or heart tissue. By locking natural proteins into tougher networks, scientists may create longer lasting scaffolds for many injured organs.

Finally, the project highlights the value of linking engineering, medicine, and patient experience. The team did not just chase a new material. They focused on a daily problem that affects millions of people and asked how chemistry and tissue engineering could offer a kinder, more durable solution.

Research findings are available online in the journal Biomaterials.

Related Stories

- Smart nanogel targets and destroys most-feared, antibiotic-immune bacterium

- New protein gel regenerates tooth enamel — revolutionizing dental health

- Saliva-releasing gel may offer long-term relief for dry mouth sufferers

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Writer

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs to historical discoveries and innovations. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.