New MIT mRNA therapy restores immune defenses lost with age

New research shows liver-targeted mRNA can restore immune strength in aging mice, boosting vaccines and cancer therapy.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

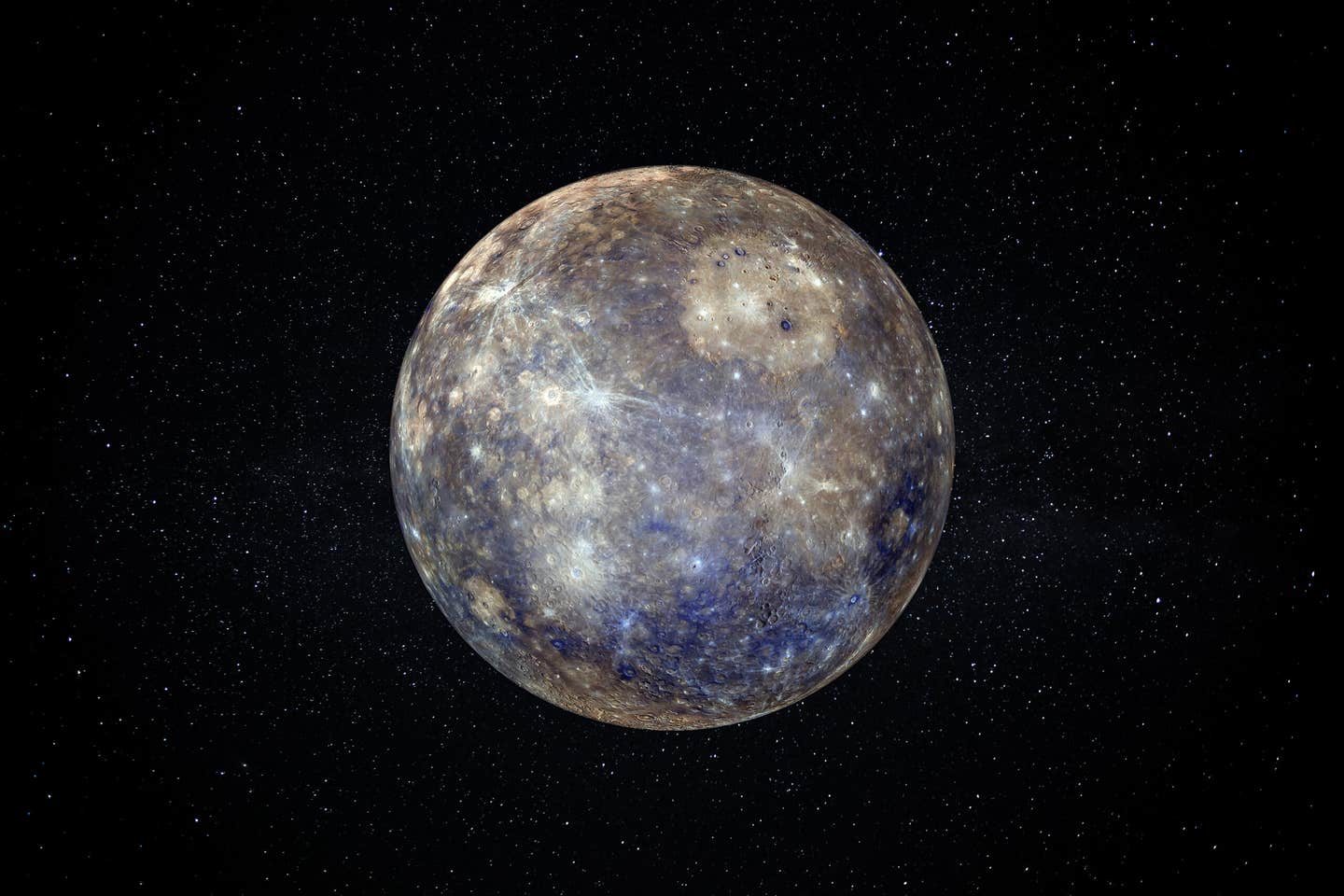

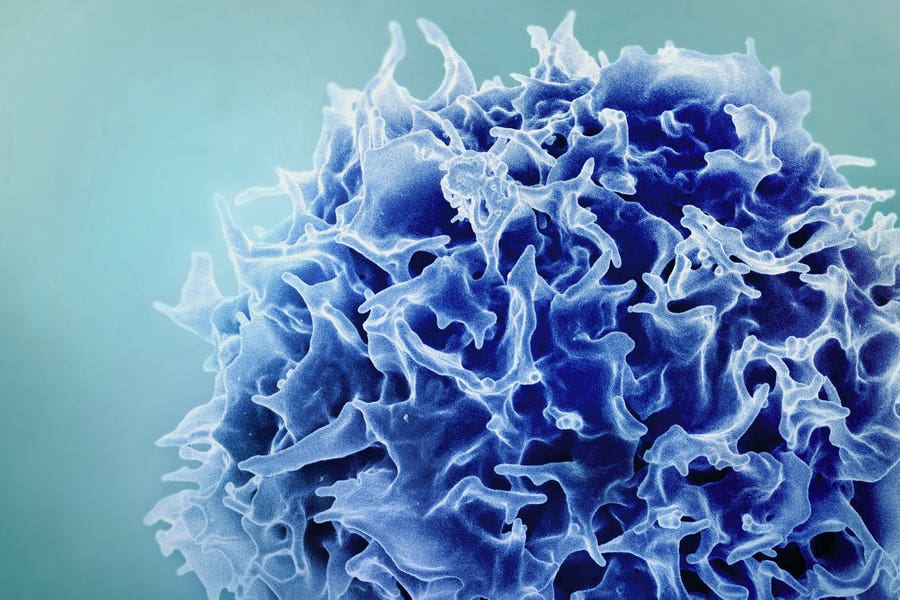

MIT researchers have discovered a way to enlist the liver to counter age-related declines in T-cells (shown), restoring their numbers and boosting the body’s response to vaccination. (CREDIT: NIAID)

Immune protection fades with time, and much of that decline traces back to the thymus. This small organ, located in front of the heart, trains new T cells and releases signals that help them survive. As adulthood progresses, the thymus steadily shrinks. This process, called thymic involution, reduces the supply of fresh, naive T cells, narrows the range of T cell receptors and weakens defenses against infections, vaccines and cancer. Older T cells also drift into exhausted or dysfunctional states, raising the risk of severe illness and tumor growth.

Many research efforts have tried to slow immune aging by reviving the thymus itself. Hormones, cytokines, small molecules and even shared blood circulation between young and old animals have all been tested. Other strategies have focused on reprogramming blood stem cells. These approaches have improved scientific understanding, but most have shown limited benefits, serious side effects or major barriers to clinical use.

A new study takes a different path. Instead of repairing the aging thymus, researchers turned the liver into a temporary source of immune-supporting signals. By delivering carefully chosen messenger RNAs into liver cells, the team restored key signals that normally decline with age. In mice, this approach improved vaccine responses, strengthened cancer immunotherapy and avoided clear signs of toxicity or autoimmunity.

Identifying What the Aging Immune System Loses

To decide which signals to restore, the researchers first mapped how immune communication changes over a lifetime. They analyzed nearly 97,000 T cell transcriptomes from peripheral blood and used spatial Slide-TCR-seq to examine more than one million locations in mouse thymus tissue. Samples covered ages from birth to 90 weeks.

As mice aged, naive and stem-like T cells declined. These cells normally express genes such as Tcf7, Sell and Ccr7. At the same time, memory-like and exhausted T cell states expanded, marked by genes linked to immune fatigue and inhibition. Similar shifts have been reported in older humans, helping explain why immune responses weaken with age.

Spatial analysis revealed that signaling between cortical thymic epithelial cells and developing T cells dropped sharply over time. In contrast, interactions in the thymic medulla remained more stable. Among the signals that faded most were Notch1 and Notch3 pathways, IL-7 signaling and soluble FLT3-L. These findings pointed to three central factors that decline with age: DLL1, IL-7 and FLT3-L.

The team deliberately chose DLL1 over a related ligand, DLL4. DLL4 is closely tied to blood vessel changes and can overly restrict immune development. DLL1 offered a safer balance, supporting T cell growth without suppressing B cells, which are essential for antibody production.

Turning the Liver Into a Temporary Immune Factory

Rather than delivering these factors as proteins, the researchers encoded them as mRNA. Proteins often clear quickly from the bloodstream and require high doses that raise toxicity risks. mRNA offers a short-lived, controllable alternative.

"We selected the liver as the production site because it retains strong protein-making capacity even in old age. It is also easier to target with lipid nanoparticles, and all circulating immune cells pass through it. Our team packaged mRNAs for Dll1, Flt3l and Il7, a combination called DFI, into SM-102 lipid nanoparticles similar to those used in some vaccines," Feng Zhang, the James and Patricia Poitras Professor of Neuroscience at MIT and senior author of the study told The Brighter Side of News.

Once delivered, the liver cells produced surface-bound DLL1 and secreted active IL-7 and FLT3-L. In mice, translation occurred mainly in hepatocytes, with little off-target activity. DLL1 expression lasted about two days. mRNA-derived FLT3-L reached higher blood levels than recombinant protein, while mRNA-derived IL-7 produced steadier, lower peaks. Some IL-7 also remained bound within liver tissue, forming a local reservoir for passing immune cells.

Importantly, four weeks of DFI dosing in aged mice did not alter body weight, liver enzymes or basic liver function. Liver tissue showed minimal inflammation. In contrast, similar dosing with recombinant proteins triggered strong inflammatory cytokine responses.

Rebuilding T Cells and Immune Balance

The central question was whether this strategy could reverse immune aging. Aged mice received DFI twice weekly for 28 days. Only the full three-factor combination increased both the number and proportion of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in blood and spleen. IL-7 alone mainly expanded memory-like cells, while DFI shifted the balance back toward a youthful profile.

T cell receptor sequencing showed no rise in clonality, suggesting new T cells were being produced rather than a few clones expanding. The thymus itself showed partial recovery. Its mass and cellularity increased, early thymocyte stages expanded and markers of recent thymic output rose in the blood.

In bone marrow, DFI boosted common lymphoid progenitors, which normally decline with age. It also restored gradients of CCR9+ progenitors that home to the thymus. These results suggest a coordinated effect, improving both T cell production and recruitment.

Other immune compartments improved as well. The spleen showed an expansion of conventional type 1 dendritic cells, which are important for antigen presentation and typically decline in older animals. These cells expressed higher levels of co-stimulatory molecules linked to effective T cell activation. At the same time, age-associated B cells declined, while mature follicular B cells increased.

Better Vaccines and Stronger Cancer Responses

Cellular changes translated into functional benefits. In an ovalbumin vaccination model, aged mice normally mount weak CD8+ T cell responses. After DFI treatment, these mice produced about twice as many antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Their cells proliferated more and released higher levels of IL-2 and IFNγ.

Across multiple age groups, DFI shifted vaccine responses in older mice to levels similar to animals about 24 weeks younger. This effect suggests a partial reset of immune aging rather than a simple boost.

Cancer models showed similar gains. In melanoma and colon carcinoma models, aged mice typically respond poorly to PD-L1 checkpoint blockade. After DFI preconditioning, tumor control improved. In the aggressive melanoma model, 40 percent of treated aged mice completely rejected tumors, while all untreated controls died within weeks.

Tumors from treated animals contained more CD8+ T cells and a more diverse T cell receptor repertoire. Exhaustion markers were lower, and a larger fraction of tumor-specific T cells retained a naive-like state.

Safety, Limits and What Comes Next

Boosting immunity raises concerns about autoimmunity. The researchers tested DFI in several sensitive models. In diabetes-prone mice, the treatment did not alter disease onset. In mice expressing ovalbumin as a self-antigen, DFI did not break immune tolerance. In a model of multiple sclerosis-like disease, peripheral immune responses increased without worsening symptoms or tissue damage.

The effects were also reversible. Markers of thymic output returned to baseline weeks after treatment stopped. Some immune changes persisted, but vaccine benefits faded if vaccination was delayed.

"Together, the findings suggest that temporary liver-based mRNA delivery can restore key immune signals lost with age. The approach improved vaccine responses and cancer immunotherapy in mice without obvious harm. Whether this strategy will translate to people remains unknown, but we believe that the concept opens a new path for treating immune aging," Zhang shared with The Brighter Side of News.

“If we can restore something essential like the immune system, hopefully we can help people stay free of disease for a longer span of their life,” he continued.

Practical Implications of the Research

This research points toward short-term treatments that could temporarily strengthen immune defenses in older adults. Such therapies might be used before vaccination, surgery or cancer immunotherapy to improve outcomes.

By restoring signals rather than permanently altering organs, the approach may reduce long-term risks. If proven safe in humans, it could help extend healthy years by reducing infections, improving cancer treatment responses and supporting immune resilience later in life.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Related Stories

- Stanford researchers cure type 1 diabetes in mice by resetting the body's immune system

- New antibody restores immune system to fight pancreatic cancer

- Exercise may restore immune system in people with long COVID

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.