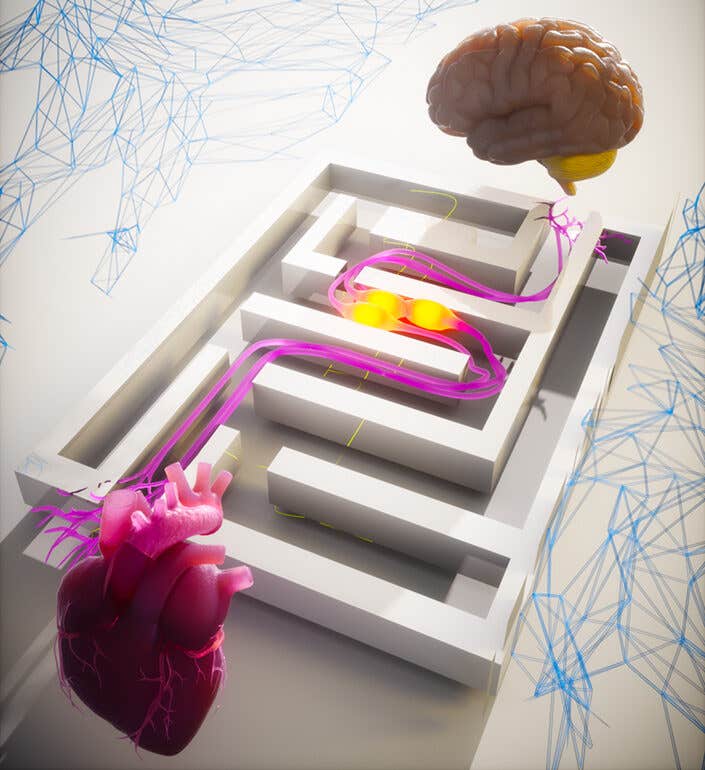

New research links the heart to the brain, nerves, and immune defenses

UC San Diego researchers report that a heart attack sparks a nerve-to-brain-to-immune loop. Blocking key signals reduced damage in mice.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

UC San Diego maps a heart-brain-immune loop after heart attack, revealing targets that reduced damage in mice. (CREDIT: Augustine Lab, UC San Diego)

Arteries can narrow with fatty buildup. Blood struggles to move. Oxygen drops. A heart attack can follow, and it remains the world’s top killer.

Researchers at the University of California San Diego say the usual way of studying a heart attack misses a key point. The heart does not act alone. In Cell, UC San Diego School of Biological Sciences scientists; led by Postdoctoral Scholar Saurabh Yadav and Assistant Professor Vineet Augustine; describe a linked system that ties the heart to the brain, nerves, and immune defenses.

Their work builds a new picture of what happens after a myocardial infarction, also called an MI. Instead of treating the heart as an isolated organ, you can view a heart attack as a body-wide event that sets off a fast chain of signals.

A heart attack sends messages your brain can hear

The team describes the body as having internal sensing, much like sight and hearing. Just as eyes and ears convert light and sound into signals the brain can use, a damaged heart can send information to the brain through sensory neurons. That internal sensing has a name in the field: cardioception.

“We believe this is the first comprehensive characterization of a “triple node” approach featuring a heart, brain and neuroimmune loop,” said Augustine, a faculty member in the Department of Neurobiology. “Heart attacks are obviously centered in the heart, but we’re flipping the switch on heart attack research to show that it’s not just the heart itself that is involved.”

In this model, the brain reads a heart attack as an injury and pushes the immune system into action. That response helps when germs cause the damage. A heart attack is different. No bacteria or virus drives the injury. So an immune surge can become harmful and can worsen tissue loss.

The researchers worked in mice to map the pathway. They brought together neurobiologists with scientists from UC San Diego’s Departments of Medicine and Pediatrics in the School of Medicine, plus the Shu Chien-Gene Lay Department of Bioengineering in the Jacobs School of Engineering. Augustine said the team had to cross disciplines because “science is traditionally established in silos.”

The first node; a vagus nerve alarm that grows after injury

The first node sits in the peripheral nervous system. Sensory neurons in the vagus nerve detect damage in the heart and send signals upward. The researchers focused on a subset of vagal sensory neurons that express TRPV1, a marker linked to injury-sensing nerve cells.

"Single-cell RNA sequencing showed TRPV1 vagal sensory neurons formed a distinct group, separate from other vagal neuron types such as PIEZO2 mechanosensory neurons. That separation suggested that a heart injury signal may travel on specific nerve cell types, not on every vagal pathway," Augustine explained to The Brighter Side of News.

"After our team induced MI in mice by permanently ligating the left anterior descending coronary artery, TRPV1-expressing vagal sensory neurons increased compared with sham animals. TRPV1-positive nerve fibers also expanded inside the ventricle, especially in the border zone around the core injury," he added.

High-resolution imaging added detail. Tissue clearing and light sheet microscopy showed TRPV1 fibers wrapping toward the border zone along a posterior-to-anterior axis. In plain terms, you see new injury-sensing wiring appear where the heart is stressed.

Reducing damage and preserving function

More nerve fibers raise a practical question. Do these signals help healing, or do they drive harm? The team tested that by turning off TRPV1 pathways and tracking heart function and scarring.

They first applied resiniferatoxin, or RTX, on the heart surface before MI. RTX is an ultrapotent TRPV1 agonist that can ablate TRPV1-positive fibers. Two weeks after MI, echocardiography showed improved ejection fraction in treated mice, with values approaching baseline. The team then used a more targeted method by injecting RTX into the nodose-jugular ganglia to ablate TRPV1 vagal sensory neurons.

That targeted ablation protected electrical and mechanical function. MI mice often develop a pathological inversion of the QRS complex on ECG. Mice with TRPV1 vagal sensory neuron ablation kept normal QRS complexes. Ultrasound results also improved, including ejection fraction, fractional shortening, and left ventricular size and volume during systole and diastole.

Biology inside the heart shifted too. Treated mice showed reduced myocardial tyrosine hydroxylase, a marker of sympathetic nerve fibers. Markers linked to growth and blood vessel formation increased, including Ki67, CD31, and VEGF. Troponin T levels dropped, and staining showed smaller infarcts and less scarring. Inflammatory signals also fell; IL-1β and TNF-α decreased after ablation.

“Blocking this heart-brain-neuroimmune system was shown to stop the spread of the disease,” said Yadav. “If you think of a heart attack as the epicenter, the blockage of the signals stopped the spread of the injury.”

The brain and sympathetic node complete the loop

The second node sits in the brain. Vagal sensory neurons send signals to brain structures, and the team points to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, called the PVN, as a key integration site.

After MI, the PVN showed increased cFos expression, which indicates neuronal activation. When the researchers ablated TRPV1 vagal sensory neurons, PVN activation dropped back toward sham levels. Activated PVN neurons also colocalized with angiotensin II receptor type 1, or AT1aR, giving the team a defined brain cell group to test.

Chemogenetic inhibition of PVN AT1aR neurons produced improvements similar to TRPV1 ablation. Awake ECG recordings showed preserved QRS patterns and an improved SD1/SD2 ratio, which the study interprets as a rebalance of autonomic tone. The team noted a key detail. Isoflurane anesthesia reduces heart rate variability and can hide the change, so awake recordings mattered.

The third node sits in the sympathetic nervous system and points back to the heart. The team identified the superior cervical ganglion, or SCG, as a sympathetic node that changes after MI. They screened multiple ganglia for inflammatory markers and found a selective rise of IL-1β in the SCG. Tracing experiments confirmed direct SCG-to-heart innervation, and SCG-derived fibers intensified after MI while targeting the border zone.

Blocking IL-1β in the SCG improved outcomes. An IL-1β-neutralizing antibody injected into the SCG after MI preserved QRS patterns and improved echocardiography measures. Sympathetic fibers decreased in the border zone, while Ki67, CD31, and VEGF increased. Scarring and wall injury also fell. A complementary test supported cause-and-effect. Injecting IL-1β into the SCG of healthy mice reduced ejection fraction and worsened left ventricular measures.

Together, the results outline a direction: heart injury signals rise through TRPV1 vagal sensory neurons to the PVN, and then sympathetic output through the SCG feeds back to the heart. Immune signaling, especially IL-1β in the SCG, appears tied to harmful remodeling.

“Current treatments for heart attacks focus on repairing the heart, including bypass surgery, angioplasty and blood thinners, which are all invasive,” said Augustine. “This research is showing that perhaps by manipulating the immune system we can drive a therapeutic response.”

Augustine’s lab is now studying the mechanisms that link the three nodes and how they shape recovery.

Practical implications of the research

This work suggests that better recovery may come from treating heart attacks as network events, not heart-only crises. You could eventually see therapies that reduce harmful immune overactivation after MI, instead of focusing only on reopening arteries and repairing muscle.

The study also offers multiple possible intervention points. You could target injury-sensing TRPV1 vagal neurons, brain integration cells in the PVN, or inflammatory signaling in the SCG. If future studies confirm similar circuits in people, doctors might add less invasive treatments that limit remodeling, reduce arrhythmia risk, and lower the chance of heart failure after a heart attack.

The “triple node” map also gives researchers a shared framework. Cardiologists, neuroscientists, and immunologists can test the same pathway with compatible tools, which may speed translation from lab findings to clinical trials.

Research findings are available online in the journal Cell.

Related Stories

- Experimental RNA drug helps hearts heal after heart attacks

- Tiny microneedle patch shows promise fighting heart attacks

- New gene discovery can help repair heart damage from heart attack or heart failure

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Mac Oliveau

Writer

Mac Oliveau is a Los Angeles–based science and technology journalist for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication focused on uplifting, transformative stories from around the globe. Passionate about spotlighting groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, Mac covers a broad spectrum of topics including medical breakthroughs, health and green tech. With a talent for making complex science clear and compelling, they connect readers to the advancements shaping a brighter, more hopeful future.