New sensor captures DNA breaks, repair inside living cells in real time

New Utrecht sensor tracks DNA damage and repair in real time, boosting cancer research, drug safety testing and aging studies.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

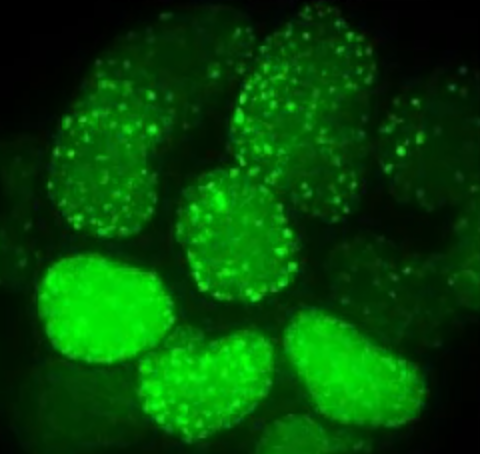

Scientists at Utrecht University created a gentle fluorescent sensor that tracks DNA damage and repair in living cells and animals, reshaping cancer and aging research. (CREDIT: Nature Communications)

In a quiet lab at Utrecht University, researchers have built a tool that lets you watch one of life’s most serious crises unfold in real time. Inside every cell, DNA breaks, repairs, and sometimes fails to heal. Until now, you could only see this drama as frozen snapshots. Now, a new fluorescent sensor lets scientists follow the full story inside living cells and even inside living animals.

The work links basic cell biology with cancer research, drug safety testing and the science of aging. It gives you a moving picture of DNA damage and repair, instead of a stack of still images that miss most of the action.

A New Window Into Everyday DNA Damage

Every moment, your DNA faces attacks from sunlight, chemicals, radiation and normal metabolism. Your cells fix most of this damage quickly. When repair goes wrong, the results can include cancer, faster aging and other serious diseases.

For decades, scientists tried to understand these repair systems, but the best tools forced them to kill and fix cells before taking pictures. That approach showed where damage had been, not how it formed, changed and disappeared over time. You could infer the story, but you could not watch it unfold.

The Utrecht team set out to change that. They designed a fluorescent “sensor” protein that glows at sites of broken DNA, then lets go again, all while the cell stays alive and working. The sensor reads a specific damage signal and turns it into visible light under the microscope.

Lead researcher Tuncay Baubec describes the idea simply. He wanted a way to look inside the cell “without disrupting the cell.”

Building a Gentle DNA Damage Sensor

Instead of inventing something completely new, the group borrowed parts from the cell’s own toolkit. They focused on a small region of a natural protein that normally helps recognize damaged DNA. This region briefly attaches to a chemical mark that appears when the cell detects a dangerous break.

“Our sensor is different,” Baubec says. “It’s built from parts taken from a natural protein that the cell already uses. It goes on and off the damage site by itself, so what we see is the genuine behaviour of the cell.”

To make the sensor visible, the researchers fused this binding region to a fluorescent tag. When DNA breaks, the mark appears, the sensor binds for a short time and a bright spot appears under the microscope. Because the interaction is gentle and reversible, the probe lights up the break without blocking or slowing the repair machinery.

Biologist Richard Cardoso Da Silva, who engineered and tested the tool, remembers the first time the sensor proved itself. “I was testing some drugs and saw the sensor lighting up exactly where commercial antibodies did,” he says. “That was the moment I thought: this is going to work.”

Turning Snapshots Into a Live Movie

The difference from older methods is striking. Before, if you wanted to track ten moments in a repair process, you often needed ten separate dishes of cells and ten separate experiments. Each dish had to be treated, fixed and stained at a different time point.

Now, with the Utrecht sensor, you can follow the same cells for hours. You can see when damage appears, how quickly repair factors arrive, and how long it takes before the glowing spots fade. Cardoso Da Silva explains that you get more data, finer detail and, most importantly, a view that matches what actually happens in living cells.

Crucially, the team checked that the probe behaves like a quiet observer. In human cell lines, repair proteins still gathered normally at break sites. The timing of repair, measured by the loss of the damage mark over time, matched cells that did not carry the sensor. Cell survival after damage stayed unchanged. The sensor watched the process; it did not steer it.

From Cells in a Dish to Living Organisms

The researchers wanted to know if this tool would still work in a real body, where cells live in complex tissues. Collaborators at Utrecht University introduced the sensor into the tiny worm Caenorhabditis elegans, a favorite model in biology.

In the worm’s germline, where reproductive cells form, the sensor lit up during meiosis, a stage when cells intentionally break and then repair DNA to shuffle genes. When the team reduced levels of the enzyme SPO-11, which normally creates these deliberate breaks, the glowing spots dropped sharply. That result showed that the tool can pick up natural damage events in a living animal.

The probe also performed well in parts of the genome that are hard to study. In mouse stem cells, it found breaks inside dense, repetitive DNA near the chromosome centers. Many tools struggle in such tightly packed regions. This sensor still homed in on the damage signal there, which increases your ability to study breaks across the full genome.

Mapping Damage Across the Genome

The group then tested whether the sensor could see targeted cuts, not just random damage. Using gene editing systems that direct a cutting enzyme to one or a few precise sites, they watched the sensor form bright foci exactly where the breaks occurred. When they used an inactive version of the cutting enzyme that could bind DNA but not cut it, the sensor no longer gathered at those spots. That confirmed that it responds to real breaks, not just to proteins sitting on the DNA.

For a final, more global test, the team used human cells in which a special enzyme can create many controlled breaks around the genome. They combined the sensor with sequencing-based methods to map where it had bound. The result matched known damage markers at more than a thousand sites with high precision. In many cases, the probe could even replace antibodies in these mapping experiments.

A More Honest View of Cellular Stress

Together, these tests show that the Utrecht sensor gives you a cleaner, more dynamic picture of DNA damage and repair than earlier methods. The sensor works in different cell types, in crowded regions of the genome and in a whole organism. It sees both intentional breaks and harmful ones. It also reports damage marked by the cell’s own signaling system and then lets the cell carry on with its work.

For you as a reader, the emotional weight sits in what this reveals about your own body. Inside each of your cells, invisible breaks and repairs happen every day. This new tool turns that hidden struggle into something you can watch, frame by frame, in real time.

Practical Implications of the Research

Although the sensor is not a therapy, it could strongly shape future medicine and biology. In cancer research, many drugs work by breaking the DNA of tumor cells. With this tool, scientists can watch how quickly different tumors repair damage and which drugs overwhelm those repairs. That could help match patients to treatments that work best on their specific cancer and reduce exposure to drugs that only cause side effects.

Drug safety testing may also become more accurate and less costly. Today, many labs rely on antibody-based methods to measure DNA damage from new compounds. Baubec notes that “clinical researchers often use antibodies to assess this.” The new sensor could speed up those tests, lower costs and sharpen the measurements, giving you safer medicines and clearer labels.

Aging research stands to gain as well. Because accumulated DNA damage and repair failure are tied to getting older, scientists can now track how these processes change across the lifespan of cells, tissues and whole animals. That may help explain why some cells age faster and why some people carry higher risk for certain diseases.

The sensor also offers practical benefits for environmental and occupational health. Researchers could use it to study how pollution, radiation or industrial chemicals affect DNA inside living cells. That knowledge can guide regulations, workplace protections and personal choices that lower your exposure to harmful agents.

On the scientific front, the tool gives biologists a way to connect where and when breaks occur with later mutations, chromosome changes and disease risk. It will likely inspire new models of genome stability and provide more honest tests of theories about how chromatin structure shapes repair. In short, it brings you closer to understanding how your cells hold their DNA together over a lifetime, and how that balance sometimes fails.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Related Stories

- Microscopic DNA ‘flower’ robots shapeshift for targeted medicine delivery

- New DNA tool detects ‘zombie cells’ linked to Alzheimer’s and arthritis

- Study finds viral junk DNA plays critical role in human development

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Writer

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs to historical discoveries and innovations. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.