New study uncovers the formative conditions that made Io dry and Europa watery

Models suggest Jupiter’s moons Io and Europa formed with different building blocks from the start, not through later water loss.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

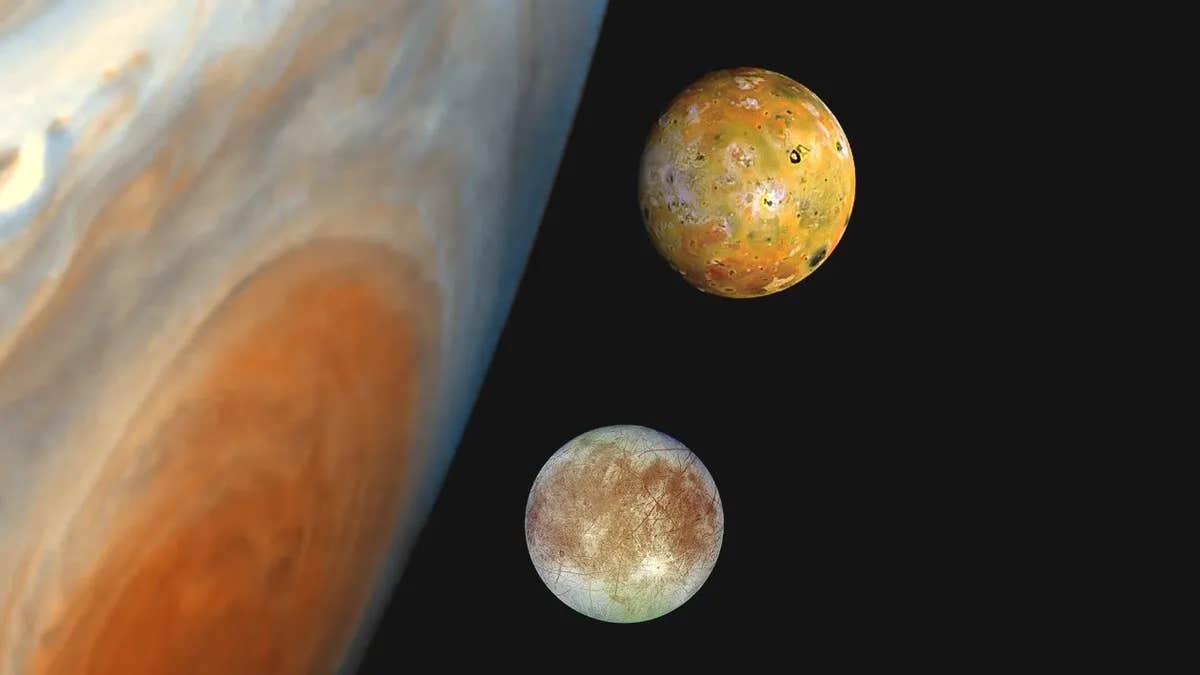

A new model suggests Io formed dry and Europa formed water-rich, with the contrast set during their birth around Jupiter. (CREDIT: NASA)

A moon can sit next door to another and still feel like a different world.

Around Jupiter, that contrast shows up fast. Io looks scorched and bone-dry, yet it is the most volcanically active moon in the solar system. Europa, just one orbit farther out, wears a shell of ice and is thought to hide a global ocean of liquid water beneath it.

A new international modeling study co-led by Aix-Marseille University and the Southwest Research Institute argues that this split did not emerge later. The difference was there from the start, baked into the materials each moon accreted as they formed around Jupiter.

“Io and Europa are next-door neighbors orbiting Jupiter, yet they look like they come from completely different families,” said SwRI’s Dr. Olivier Mousis, second author of an Astrophysical Journal paper detailing these findings. “Our study shows that this contrast wasn’t written over time — it was already there at birth.”

Two competing origin stories

For years, researchers have weighed two broad explanations for the Galilean moons’ water gradient.

One idea ties it to Jupiter’s circumplanetary disk, the swirling material that fed the growing planet and its satellites. In that picture, temperature ruled everything. The inner region stayed too warm for ice to survive, so moons that formed closer in started out drier. Farther out, beyond the snowline, water ice could condense and accumulate.

A second idea flips the story. It suggests that all four large moons began water-rich, perhaps even as ocean worlds. Then the inner moons, especially Io, lost their volatiles later. Mechanisms proposed for that loss include hydrodynamic atmospheric escape during warm early phases, plus ongoing heating that could keep water in a vulnerable state.

The new study set out to test which story the physics supports for Io and Europa. The team focused on a specific pathway for “starting water,” rather than assuming piles of surface ice. They assumed water entered the young moons mainly through hydrated minerals, rocks that contain water bound in their structure.

Putting early Jupiter to work in a model

To replay the earliest stages, the researchers coupled two linked pieces of physics: the moons’ internal thermal evolution and the loss of volatiles from the surface.

They accounted for major heat sources expected in the young Jovian system. Those included accretional heating during growth, radioactive decay, tidal dissipation, and Jupiter’s intense radiation. As the models warmed the interior, hydrated minerals could dehydrate, releasing water that would migrate toward the surface and build a hydrosphere.

Then the escape model took over. If surface temperatures rose enough to form a surface ocean, that ocean would feed a vapor atmosphere. Under low gravity and warm conditions, the atmosphere could flow off in a thermally driven, hydrodynamic wind.

The study explored two end-member growth styles because the size of incoming material matters. In one, the moons accreted “pebbles,” smaller particles that deliver energy differently. In the other, they grew through kilometer-scale impactors, called satellitesimals, which can punch deeper and deposit more heat inside the body.

“Io has long been seen as a moon that lost its water later in life,” Mousis explains. “But when we put that idea to the test, the physics just refuses to cooperate: Io simply can’t get rid of its water that efficiently.”

When water refuses to leave

The models showed a stubborn result. Once a body like Io develops an established hydrosphere and then cools enough to freeze, removing the remaining water becomes extremely hard.

The work argues that neither tidal heating nor other late processes can efficiently eliminate a fully formed ice-rich shell over long timescales. The authors also note that sputtering by Jupiter’s magnetospheric plasma, while real today, would need to be vastly stronger to strip a meaningful fraction of a primordial ocean within about 10 million years. Their estimate says it would take sputtering rates far above what existing studies suggest.

Europa, in the same framework, also resists losing water. Even when the team pushed toward conditions that maximize escape, Europa generally retained volatiles under most scenarios.

That matters because it undercuts the simple “both started wet, one dried out” narrative. If Io begins with substantial water, the model struggles to empty it. If Europa begins with substantial water, the model says it should still have most of it.

So the cleanest way to match what we see today is to start them different.

“The simplest explanation turns out to be the right one,” Mousis said. “Io was born dry, Europa was born wet — and no amount of late-stage evolution can change that.”

A narrow window for a water-stripped Io

The paper does not claim Io could never lose volatiles. It outlines conditions that can reproduce Io’s present density, but the window looks tight.

In pebble-accretion scenarios, full volatile loss becomes possible only if at least one strong condition holds. The moon must form very close to Jupiter, or accrete very quickly, or rely on large impactors that accelerate dehydration. Under satellitesimal accretion, the deep heating can drive earlier dehydration, which makes complete volatile loss easier within certain distances.

Even then, the authors argue that key assumptions already favor devolatilization. They used an isothermal atmosphere to estimate an upper limit on escape. They also explored an early onset of accretion relative to CAI formation because earlier formation increases heating from short-lived radionuclides.

Despite those choices, they still conclude that Io likely could not shed a full initial water inventory. That pushes the interpretation toward a different starting composition.

In their preferred picture, Io accreted primarily anhydrous silicates. Europa accreted from ice-rich building blocks. The contrast traces back to the thermodynamic structure of Jupiter’s circumplanetary disk at the time of formation, not to dramatic later water loss.

The paper also notes a plausible way to keep inner material dry. If Io formed interior to a “phyllosilicate dehydration line,” water released from heated minerals inside that boundary could diffuse outward and recondense nearer the snowline. That would naturally feed more water to moons forming farther out.

What JUICE and Europa Clipper can test

The study points to upcoming spacecraft as a chance to check this origin story with new measurements.

Beginning in 2031, NASA’s Europa Clipper mission and the European Space Agency’s JUICE mission will study Jupiter’s large moons. The paper highlights plume sampling and compositional measurements as especially useful, since plumes can expose subsurface materials.

The authors emphasize isotopes as a key clue, especially the deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio in water. In their scenario, Europa should not have lost much water to atmospheric escape. That implies Europa’s D/H ratio should resemble values measured in hydrated asteroids and carbonaceous chondrites, and sit close to the terrestrial ocean value described in the study. The paper also outlines how Ganymede and Callisto might show different D/H values if water vapor diffused outward through the disk and exchanged isotopes before freezing out again.

Measurements from JUICE instruments and Europa Clipper’s MASPEX instrument could help constrain these histories through infrared spectroscopy and in situ sampling, according to the paper.

Research findings are available online in the Astrophysical Journal.

The original story "New study uncovers the formative conditions that made Io dry and Europa watery" is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- Salty ice may hold the key to life on Jupiter’s moon Europa

- NASA’s Juno spacecraft offers fresh insight into Europa's icy ocean and its potential to support life

- NASA spots colossal eruptions shaking Io — Jupiter’s most volcanic moon

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.