Next-gen bionic arms read nerve signals years after amputation

New implants decode single motor neuron signals in reinnervated muscles, paving the way for more natural control of bionic arms.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

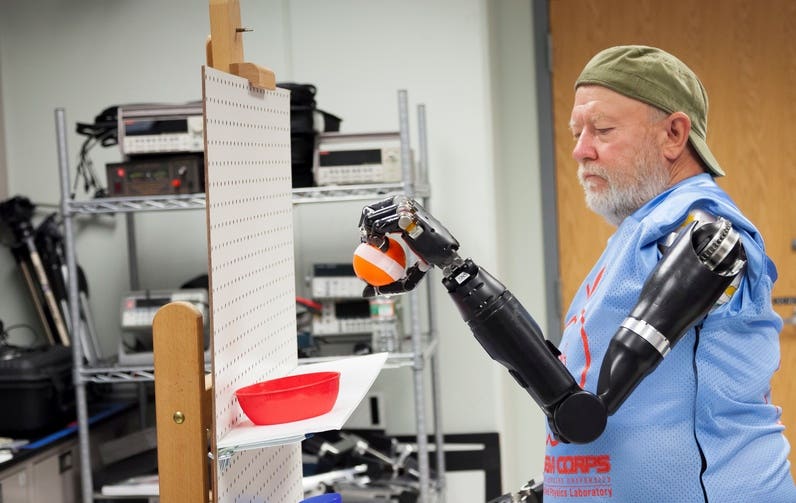

Scientists in Vienna and London have shown that even years after an arm amputation, detailed movement commands survive in the nerves. By combining targeted muscle reinnervation with implantable microelectrodes, they can decode single motor neuron signals and link them to specific finger and wrist movements, opening the door to far more intuitive bionic prostheses. (CREDIT: Johns Hopkins University)

Losing an arm cuts more than muscle and bone. It also severs the easy, wordless link between what you want to do and what your hand can actually do. For many people with prosthetic arms, that link still feels blunt and slow, more like steering a machine than moving a limb.

Now researchers in Vienna and London have taken a major step toward changing that experience. In work published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, they show that the body keeps surprisingly rich movement signals even years after amputation, and that those signals can be captured and used to drive a bionic arm with far greater precision.

Tapping Into Silent Nerves

After an amputation, the nerves that once controlled your hand and fingers stay alive inside the arm. They still carry commands from the spinal cord. They simply have nowhere meaningful to go.

To give those nerves a new target, surgeons use a technique called targeted muscle reinnervation, or TMR. In this procedure, doctors connect the cut nerve branches to spare muscles in the residual limb. Those muscles then act as biological amplifiers for the signals that used to go to the missing hand.

As part of the European Natural BionicS project, the team at the Medical University of Vienna implanted novel 40 channel microelectrodes into these reinnervated muscles in three people who had lost an arm. The volunteers had already undergone TMR, so their spare muscles were wired to hand and wrist nerves.

This combination of surgery and implanted electronics gave the scientists an unusually direct window into the nervous system. Instead of just reading broad muscle activity from the skin, they could record from deep inside the muscle where individual nerve driven signals appear.

Listening To Single Motor Neurons

The key breakthrough came from how the researchers handled those signals. Motor neurons in the spinal cord send commands to muscle fibers through long, thin axons. Each motor neuron controls a small group of fibers, called a motor unit. If you can hear single motor units, you can, in theory, hear single movement instructions.

By using the dense microelectrode arrays, scientists from Vienna and Imperial College London could, for the first time in amputees, isolate the activity of individual motor neurons in the reinnervated muscles. The electrodes acted like a high resolution microphone pressed against a noisy crowd.

The participants then performed a series of tasks with their phantom arm. They were asked to mentally extend a finger, bend a wrist, or attempt other specific movements, even though the limb was no longer there. While they did this, the electrodes recorded the tiny electrical bursts inside the muscle.

“Using our method, we were able to precisely identify the nerve signals that underlie, for example, the stretching of a finger or the bending of the wrist,” says Oskar Aszmann, who leads the Clinical Laboratory for Bionic Limb Reconstruction at the Medical University of Vienna.

Advanced algorithms separated the mixed signals into distinct firing patterns for individual motor units. The team could then link particular patterns to particular intended movements. That level of detail had never been shown in humans with an amputation.

Movement Plans Survive Amputation

One striking finding may matter most for future patients like you. Even years after limb loss, the nervous system still carries complex and structured movement plans. Those plans do not die with the arm.

When researchers analyzed the recordings, they saw that many different intended movements, such as specific finger actions, had unique fingerprints in the motor neuron activity. They could mathematically reconstruct these patterns and map them back to the original movement intention.

In simpler terms, the brain still thinks in fingers and joints, not in vague “open” and “close” commands. The spinal cord still sends detailed instructions down the nerves. TMR gives those signals a place to land, and the implanted electrodes pick them up before they fade into noise.

“This is a crucial step towards making the control of bionic limbs more natural and intuitive,” Aszmann says. Instead of driving a prosthesis with a few coarse muscle contractions, a person could, in time, control many degrees of freedom with signals that mirror the way a healthy arm works.

Toward A Bioscreen and Wireless Bionic Hands

The work does more than prove a concept. It points to a future system that the team calls a bioscreen. The idea is to build a platform that visualizes the complex neural patterns behind human movement and uses them as a live control signal for prosthetic devices.

If that vision becomes real, a clinician could one day sit with you and watch your neural patterns light up on a screen as you think about moving your missing hand. Those patterns could then be calibrated to a robotic arm in a more direct and personal way.

Current experiments still rely on wired connections from the implanted arrays to external equipment. The long term goal is to create wireless implants that sit inside the reinnervated muscles and send nerve signals in real time to bionic hands or other assistive systems. Such implants would need to be small, stable, and safe over many years.

The research groups in Vienna and London see their present work as the foundation for that step. They have shown that the necessary information exists, that it can be captured, and that it stays meaningful long after an amputation.

Practical Implications of the Research

For people living with arm loss, this research holds direct promise. More precise decoding of motor neuron activity could allow future prosthetic arms to move in ways that feel closer to a natural limb. Instead of training yourself to trigger a few clumsy motions, you could rely more on the same movement intentions you used before the injury.

Clinically, the study supports wider use of targeted muscle reinnervation. It shows that reinnervated muscles can act as powerful neural interfaces when paired with implanted sensors and smart decoding. That may influence how surgeons plan reconstructions and how early after an amputation these strategies are considered.

For engineers and neuroscientists, the findings confirm that detailed movement commands survive in the peripheral nervous system and can be read at the level of single motor units. That insight will guide the design of next generation interfaces for prosthetics, exoskeletons, and other assistive devices.

In the longer term, the concept of a bioscreen and wireless implants could reshape rehabilitation. If nerve signals can be streamed in real time to machines, many types of motor assistance might become more responsive and personalized. The same approach could also inform therapies for nerve injuries beyond amputation, helping people regain control after trauma or disease.

At a human level, the work offers something simpler and deeper. It shows that your body remembers how to move, even when a limb is gone. Those silent signals can still be heard, and with new tools, can be given a new mechanical voice.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Related Stories

- From nerves to bones: How diabetes changes the human skeleton

- Weight loss connected to nerve cells in the brain, study finds

- Human touch stimulates 16 different types of nerve cells in the body

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer