Next-generation quantum sensor sees the magnetic world in unprecedented detail

Scientists use entangled defects in diamonds to detect magnetic signals at record sensitivity, opening new doors in physics and technology.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

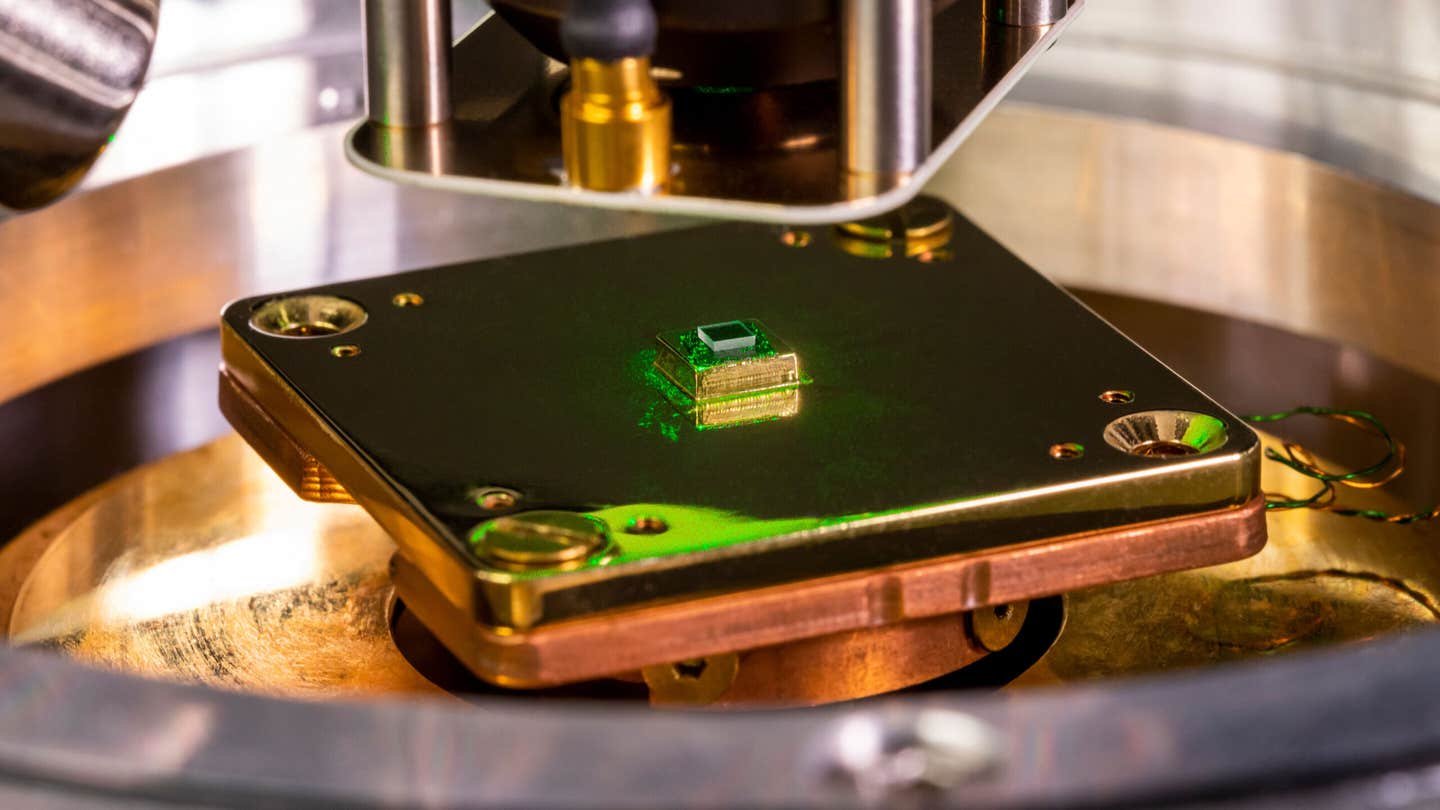

Researchers led by Nathalie de Leon have developed a magnetic sensing technique using quantum entanglement to detect previously hidden fluctuations in advanced materials such as superconductors. The researchers implant point defects in lab-grown diamonds to reveal an unprecedented look at magnetic field structure and correlated noise, a quantity that is beyond the reach of existing instruments. (CREDIT: Sameer A. Khan/Fotobuddy)

In labs around the world, scientists chase forces too faint to see and too small to touch. They hunt for tiny magnetic signals that ripple across materials atom by atom. Those signals hold clues to how tomorrow’s electronics, sensors and computers might work. Now a team at Princeton University says it has found a way to see that hidden world more clearly than ever before, using defects inside diamonds and a trick from quantum physics.

In a study published in the journal Nature, the researchers report a quantum sensor that is about 40 times more sensitive than earlier diamond-based tools. The sensors are built from engineered flaws inside lab-grown diamonds that behave like tiny magnetic compasses. When paired and linked through quantum entanglement, they act together in a way that reveals magnetic noise at scales far smaller than a beam of light can reach.

Nathalie de Leon, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and the study’s senior author, said the work opens a new window into nature’s smallest movements.

“You have this totally new kind of playground,” de Leon said. “You just can't see these things with traditional techniques.”

Diamonds with a secret flaw

The heart of the sensor is something called a nitrogen vacancy center. It sounds complex, but the idea is simple. In a perfect diamond, carbon atoms form a rigid crystal. Remove one carbon atom and replace another with a nitrogen atom, and you get a tiny defect. That flaw traps electrons whose behavior shifts when a magnetic field is nearby.

Those shifts can be read with laser light. Over the past decade, scientists have learned how to use single defects as magnetic sensors. They have studied electronic currents, tiny nuclear signals and even living cells.

Yet one problem lingered. Most experiments treated each defect as a lone watcher. Real materials, however, are messy and alive with motion. What matters is not just how strong a magnetic field is at one point, but how it changes from place to place and from moment to moment.

Existing tools struggled at that task. Techniques like neutron scattering view huge volumes at once. Scanning probes can get close to a surface but not close enough to each other. Optical microscopes cannot tell two light sources apart if they are less than about 250 nanometers away. Many of the most interesting processes occur at scales much smaller.

The Princeton team aimed right at that gap.

Seeing beneath the limit of light

First, the researchers found a way to measure magnetic links between two defects even when they glow as one blurred dot under a microscope. They used special imaging tricks to map each defect’s exact position during setup. Then, during measurement, they read the combined light from both.

To pull apart the signals, they ran a four-step sequence that flipped each quantum sensor in a planned pattern. By comparing how the total light varied in each step, they teased out how the two defects responded together. The method is drawn from nuclear magnetic resonance and works even when the sensors cannot be seen as separate points.

For trickier cases, when two defects share the same orientation and energy, the team enlisted a helper already inside the diamond. Carbon-13 atoms, a rare form of carbon, have magnetic spins of their own. When one sits near a defect, it nudges that defect in a unique way.

By tuning into that nudge, the scientists could control one sensor without touching the other. That allowed them to run the same four-step pattern and measure magnetic links at distances down to billionths of a meter.

These methods crossed a big hurdle. But they carried a drawback. Each sensor still produced its own random noise. When the team multiplied the two signals to find a link, the noise multiplied too.

The solution came from letting the sensors talk to each other in a different way.

When two sensors become one

The most dramatic leap came when the researchers placed two defects so close, about 10 nanometers apart, that they began to interact strongly. To do that, they fired nitrogen molecules into diamonds at more than 30,000 feet per second. On impact, each molecule split and the two atoms burrowed into the crystal, coming to rest a few dozen atoms below the surface.

At that distance, the two sensors became quantum partners. Their electrons locked into shared states known as entangled pairs. Change one, and the other responds instantly.

Albert Einstein once mocked the idea as “spooky action at a distance.” In this case, the spookiness pays off.

The team created two types of entangled states. In one, the pair reacts strongly to shared magnetic noise. In the other, it barely notices. By comparing how the states change under the same conditions, the scientists read out how much of the magnetic signal is linked between the two points.

“This is a very new way of operating this quantum sensor that allows us to probe something which has not been possible before,” said Philip Kim, a physicist at Harvard University who was not involved in the study.

The payoff is huge. With entanglement, the signal depends on noise in a simple, linear way. That makes the reading far cleaner. What once took hours now takes minutes, and the team can use a single green laser instead of slower methods.

“Now all I have to do is a single measurement, a single normal measurement,” de Leon said.

From pandemic idea to lab reality

The work began during the early days of COVID-19, when labs stood silent. Jared Rovny, then a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton, turned to theory.

“It started as one of these weird, Covid, theory projects,” de Leon said.

Rovny had studied nuclear magnetic resonance, where interactions matter as much as individual signals.

“That NMR side of me was really always thinking about interactions,” Rovny said.

He worked with Shimon Kolkowitz, then at the University of Wisconsin Madison, to test ways of measuring links between unentangled sensors. That effort led to a 2022 paper in Science. But the methods were hard to use and slow.

Then came the insight.

“What I realized is that if you entangled them,” Rovny said, “the presence or absence of a correlation sort of puts its fingerprint onto the system.”

Rovny is now at quantum startup Logiqal, but the idea he helped spark has reshaped what these tiny diamonds can do.

A new map of the invisible

The team also built ways to track how magnetic links evolve over time. In one method, they swap information between sensors halfway through a measurement window. In another, they overlap sensing periods to catch brief, flickering signals.

These tools let scientists follow fast changes, down to millionths of a second, and watch how magnetic patterns spread.

The impact could be wide. The sensors could expose how electrons bump through graphene, how vortices twist inside superconductors, or how noise seeps from surfaces that touch quantum devices.

Kim, who studies such materials, sees promise.

“That range is, in fact, the length scale of interest,” he said.

The approach may also reach beyond diamonds. Entangled sensors could help stabilize superconducting computers, sharpen atomic clocks and improve navigation systems that rely on faint magnetic cues.

At its core, the work shows that quantum weirdness is not just a curiosity. It can be a tool.

In spaces smaller than light’s own waves, where fields coil and currents jump, these diamond flaws now offer a look into motion once thought unreachable.

Practical Implications of the Research

The advance could change how scientists design and test new materials, especially those used in electronics, energy systems and future computers. By tracking how magnetic noise behaves at the smallest scales, researchers can better understand why devices fail, lose energy or behave unpredictably.

The sensors may help improve superconductors for medical scanners, power grids and trains that float on magnetic tracks. They could also make quantum computers more stable by revealing hidden sources of error.

In the long run, the work points toward faster, smaller and more reliable technology, all guided by clearer views into nature’s quietest signals.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Related Stories

- 50,000-year-old meteorite helps scientists create the hardest diamonds on Earth

- Levitating diamonds spin at 1.2 billion RPM to unlock quantum gravity

- Groundbreaking diamond battery generates power from nuclear waste

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Writer