Our universe may exist inside a spinning black hole, JWST finds

Webb telescope reveals unexpected galaxy spin patterns, sparking theories the universe may be inside a rotating black hole.

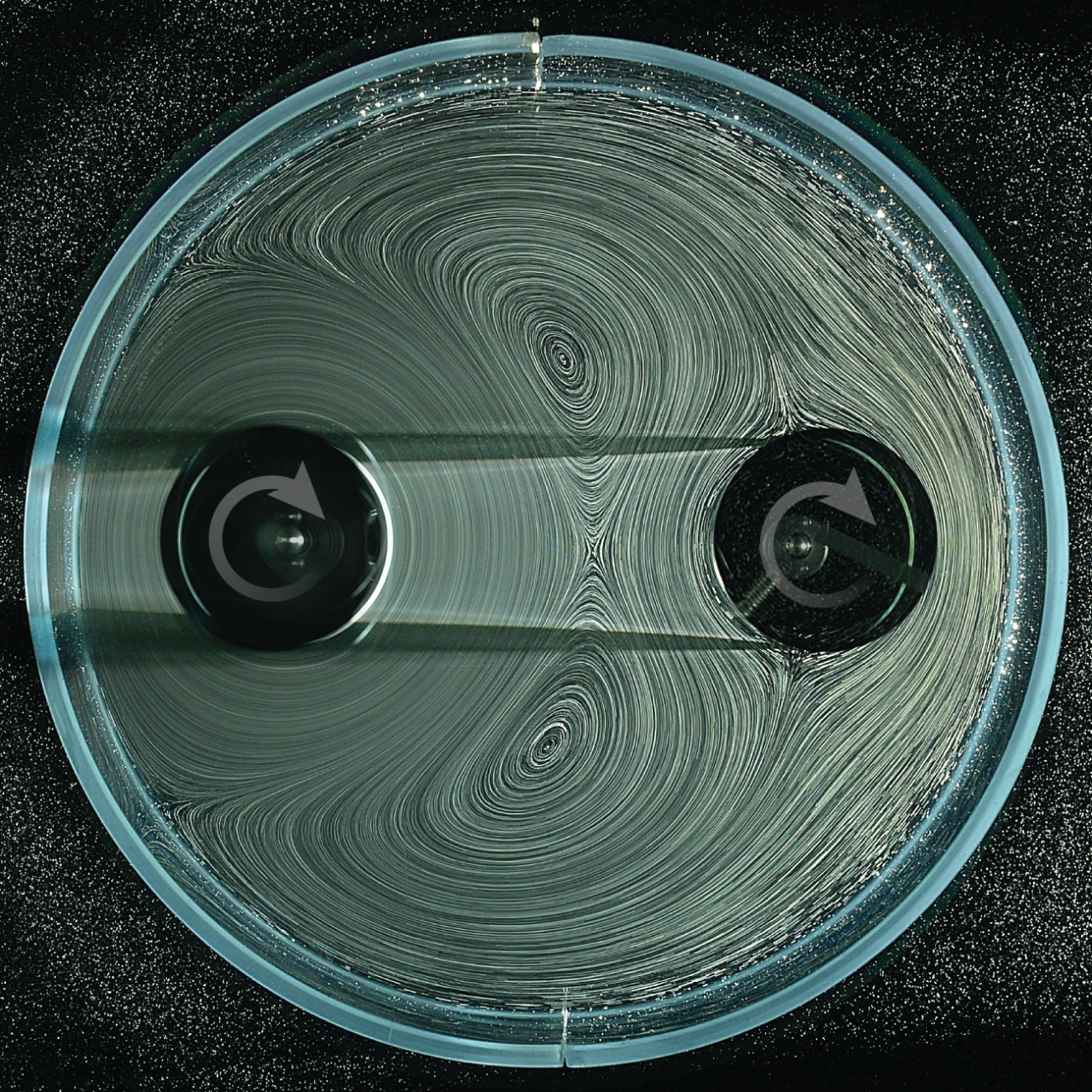

A bold theory known as black hole cosmology, proposes that our universe could exist inside a giant rotating black hole. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched in 2022, continues to reshape how we view the cosmos. Designed to look deeper into space and further back in time than any previous instrument, it has begun to uncover celestial secrets that defy long-standing scientific models. Its advanced imaging technology has spotted ancient galaxies forming just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang—far earlier than scientists thought possible.

One such galaxy, named JADES-GS-z14-0, appears to have taken shape only 250 million years after the universe began. The existence of galaxies so early in cosmic history is already rewriting theories about how galaxies evolve.

Even more puzzling, many of these early galaxies show structured spiral patterns—forms that were believed to develop much later. These findings are throwing a wrench into accepted timelines of galactic development and have sparked debates among cosmologists worldwide.

The Great Galactic Spin Mystery

Beyond age and structure, JWST has revealed something even more unusual—how galaxies spin. A recent study led by Lior Shamir at Kansas State University uncovered a strange pattern in the rotation direction of galaxies.

Using data from JWST’s Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES), Shamir examined 263 galaxies and discovered that about two-thirds rotated clockwise, while only one-third rotated counterclockwise.

In a universe assumed to be random and isotropic—meaning it has no preferred direction—this finding is deeply unsettling. Normally, scientists would expect roughly equal numbers of galaxies rotating in both directions. Yet JWST’s high-resolution imaging made the imbalance unmistakable. “The difference is so obvious that anyone looking at the image can see it,” Shamir said. “There is no need for special skills or knowledge to see that the numbers are different.”

Related Stories

These results mirror earlier hints from Earth-based telescopes, but JWST's sharper view gives the finding much greater weight. The implication? Something may be influencing the spin of galaxies on a massive scale.

Two Theories, One Big Question

Shamir and other scientists are now faced with a tough question: what could cause this unexpected imbalance? One idea is that the entire universe may have been born spinning. This notion connects with a bold theory known as black hole cosmology, which proposes that our universe could exist inside a giant rotating black hole in another, parent universe. If this were true, the axis of that parent black hole could have influenced the way our universe’s galaxies now rotate.

This theory has gained traction thanks to researchers like theoretical physicist Nikodem Poplawski at the University of New Haven. He believes that black holes might not just be endpoints of stars, but could also act as gateways to new universes.

According to Poplawski, matter inside a black hole may not collapse into a single point, or singularity, as previously believed. Instead, extreme forces could compress it into a super-dense state before it rebounds and expands—an event similar to the Big Bang.

“In this model,” Poplawski explained, “every black hole could give birth to a new universe.” That would make our universe one of potentially countless others. And since black holes spin, the rotation of our own parent black hole could explain the preferred galactic spin direction we're now observing.

He added, “The discovery by the JWST that galaxies rotate in a preferred direction would support the theory of black holes creating new universes, and I would be extremely excited if these findings are confirmed.”

A Simpler Explanation?

Despite the allure of such groundbreaking ideas, not everyone is ready to abandon conventional physics. Another explanation could be far less exotic. The rotation of our own Milky Way galaxy and the way we observe light may have influenced the JWST’s measurements.

The Doppler effect, which causes waves to shift in frequency based on motion, might make galaxies spinning in a direction opposite to our own movement appear brighter or more noticeable. This observational bias could have skewed the data.

If that’s the case, scientists may need to revisit their calculations. “If that is indeed the case, we will need to re-calibrate our distance measurements for the deep universe,” Shamir explained. Such recalibration could affect how scientists estimate galaxy ages, expansion rates, and the structure of space itself.

This is especially important because current cosmological models already face tensions. One key example is the ongoing disagreement over the universe’s expansion rate, known as the Hubble tension.

Different measurement methods are producing results that don’t align, hinting that some unknown variable may be at play. The possibility that past observations were skewed by Earth's movement adds yet another layer to this cosmic puzzle.

Could the Universe Be Inside a Black Hole?

Black hole cosmology, often called Schwarzschild cosmology, goes further by suggesting that every black hole might be a gateway to a “baby universe.” This concept, proposed decades ago by Raj Kumar Pathria and I. J. Good, describes black holes as bridges—Einstein-Rosen bridges, or wormholes—that connect one universe to another. Poplawski has expanded on this theory, suggesting that our universe’s flatness, symmetry, and directional time flow could all be explained by this birth-through-a-black-hole model.

He described how the twisting of matter, called torsion, could prevent total collapse into a singularity. Instead, the matter reaches a limit, bounces back, and begins to expand—forming a new universe inside the black hole. This bounce would drive cosmic inflation, the rapid expansion that helps explain why the universe looks so smooth and flat on a large scale.

“In this view,” Poplawski said, “our own universe could be the interior of a black hole existing in another universe.” He believes that the observed galactic spin pattern could be the inherited result of the parent black hole’s rotation. If galaxies today seem to spin mostly in one direction, perhaps it's because the entire cosmos started with that same spin.

A Shift in Cosmic Understanding

No matter which explanation proves correct—whether it's a subtle bias in measurement or a universe born from a rotating black hole—one thing is clear: the JWST is shaking the foundation of modern cosmology. Its observations are pushing scientists to question the basic principles of how the universe formed, evolved, and behaves.

These unexpected findings are more than just astronomical trivia. They challenge the idea that the cosmos is symmetrical, random, and fully explained by existing theories. As the JWST continues to send back data from the farthest reaches of space, researchers may soon have to rebuild major parts of the cosmological model.

For now, the strange spin of galaxies stands as a powerful clue—one that could lead to a much deeper understanding of where everything came from, and where it's going.

More about Einstein-Rosen bridges

Einstein-Rosen bridges, also known as wormholes, were first proposed in 1935 by Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen as a theoretical solution to the equations of general relativity. They imagined a “bridge” connecting two distant points in space-time through a tunnel-like structure, formed by extending the concept of a black hole. In theory, such a bridge could allow for shortcuts across vast distances in the universe or even link different universes.

The original Einstein-Rosen bridge was based on the mathematical structure of a Schwarzschild black hole. However, their model turned out to be unstable—it would collapse too quickly for anything, even light, to pass through. Later models, especially those introduced in the 1980s, explored ways to stabilize wormholes using hypothetical forms of matter with negative energy density, known as exotic matter.

Despite their appeal in science fiction, no observational evidence has ever confirmed the existence of wormholes. Their stability, traversability, and physical plausibility remain purely theoretical. Still, they provide a useful framework for exploring the limits of general relativity, quantum gravity, and the possibility of time travel or faster-than-light communication.

Modern physicists continue to study wormholes using advances in quantum field theory and string theory. Some recent proposals suggest that wormholes might be related to quantum entanglement, as in the ER=EPR conjecture, which links Einstein-Rosen bridges to entangled particles. While the idea is still speculative, it hints at deeper connections between space-time geometry and quantum mechanics.

Research findings are available online in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.