PHD student built the first-ever 3D map of Uranus’s upper atmosphere

Webb tracked Uranus’ faint glow to 5,000 km high, revealing auroral bands shaped by its tilted, off-center magnetic field.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

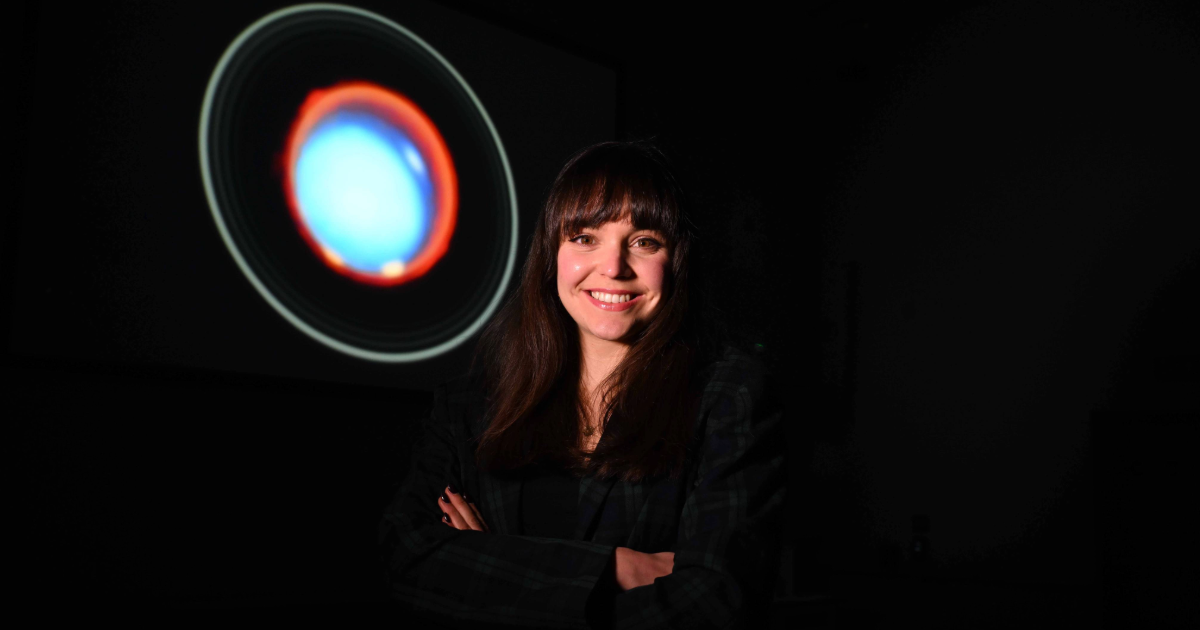

Paola Tiranti of Northumbria University. (CREDIT: Northumbria University/Barry Pells)

Uranus does not behave like an ordinary planet.

Its magnetic field tilts by nearly 60 degrees and sits off-center, so the charged particles that spark auroras do not gather in neat rings. They sweep across the ice giant in complicated paths, sometimes brightening, sometimes thinning out, depending on how the magnetic field funnels energy into the upper air.

That odd geometry now has a new kind of map.

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, an international team led by Northumbria University PhD student Paola Tiranti has produced the first three-dimensional view of Uranus’ upper atmosphere, tracking faint infrared emission from molecules as high as about 5,000 kilometers above the cloud tops. The study was published in Geophysical Research Letters.

A night-long watch on a rotating planet

The team watched Uranus for 15.4 hours on Jan. 19, 2025, close to a full rotation of the planet, which is about 17.2 hours. The data came from JWST General Observer program 5073, led by Dr. Henrik Melin of Northumbria University, using Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph Integral Field Unit.

Webb’s sensitivity matters here because Uranus’ infrared glow is faint, and Earth-based observations have struggled to pull out vertical structure at the planet’s limb. This time, the team binned the signal in 350-kilometer altitude steps from 475 kilometers up to 5,025 kilometers, then retrieved local temperatures and ion densities in the ionosphere, the region where the atmosphere becomes ionized and couples strongly to the magnetic field.

They focused on emission from H3+, a molecular ion commonly used as a remote probe of temperature and density in giant-planet ionospheres.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to see Uranus’s upper atmosphere in three dimensions. With Webb’s sensitivity, we can trace how energy moves upward through the planet’s atmosphere and even see the influence of its lopsided magnetic field,” Tiranti said.

Heat high up, ions lower down

The new profiles show that Uranus’ upper atmosphere does not peak in temperature where its ion density peaks.

Across the globe, the team found temperatures rising from about 419 K at 475 kilometers to a peak of 470 K at roughly 3,625 kilometers, then decreasing with height. In plain terms, the warmest layer sits between about 3,000 and 4,000 kilometers above the cloud tops.

Ion densities peaked much lower, just above 1,000 kilometers. The paper reports the peak at 1,175 kilometers.

Those two peaks matter because they hint at how energy is deposited and redistributed. The team also compared how total infrared emission relates to temperature and density at different altitudes. In the 3,000 to 4,000 kilometer band, emission correlated more strongly with temperature than with density, suggesting thermal processes dominate the glow at those heights.

Lower down, around the density peak, the pattern flipped.

Two bright bands and a dim gap

Webb’s data also picked up structure in Uranus’ auroras that matches the planet’s unusual magnetic field.

The observations show two bright auroral bands near the magnetic poles, along with a distinct region between them where emission and ion density drop. The team links that depleted zone to how magnetic field lines guide charged particles through the atmosphere.

Similar darker regions have been seen at Jupiter, where magnetic geometry helps control particle flow.

The study notes that the bright emission regions extended over large longitude ranges, around 50 degrees, even though other observations, including from JWST and the Hubble Space Telescope, have often shown compact, spot-like brightenings.

Coverage is a constraint. The Jan. 19, 2025 observations included latitudes between 25°N and 25°S, and the authors flag that the southern aurora is only partly sampled in their geometry.

The long cooling trend still holds

One result in the paper is not about auroras at all.

Uranus’ upper atmosphere has been cooling for decades, and Webb’s measurements extend that trend. The team reports a column-weighted temperature of 426 K, cooler than values reported in earlier ground-based work, and slightly higher than a JWST disk-averaged temperature of 415 K that the authors attribute to differences in what parts of the planet are emphasized.

Why the planet is cooling remains an open question inside the paper’s frame. The discussion notes that the decline has been attributed to reduced solar wind power, though that explanation is described as debated.

The authors also point to limits in how the infrared signal behaves at very low densities. At high altitudes, where H3+ becomes sparse, non-local thermodynamic equilibrium effects may shape the retrieved profiles. They also state that their profiles become unreliable above 5,025 kilometers, and typical uncertainties stay under 10% up to that altitude.

Research findings are available online in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The original story "PHD student built the first-ever 3D map of Uranus's upper atmosphere" is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- Uranus’s extreme radiation belts linked to ancient solar wind event

- Rethinking the “Ice Giants”: Uranus and Neptune may be rockier than we thought

- James Webb Telescope finds hidden moon orbiting Uranus

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.